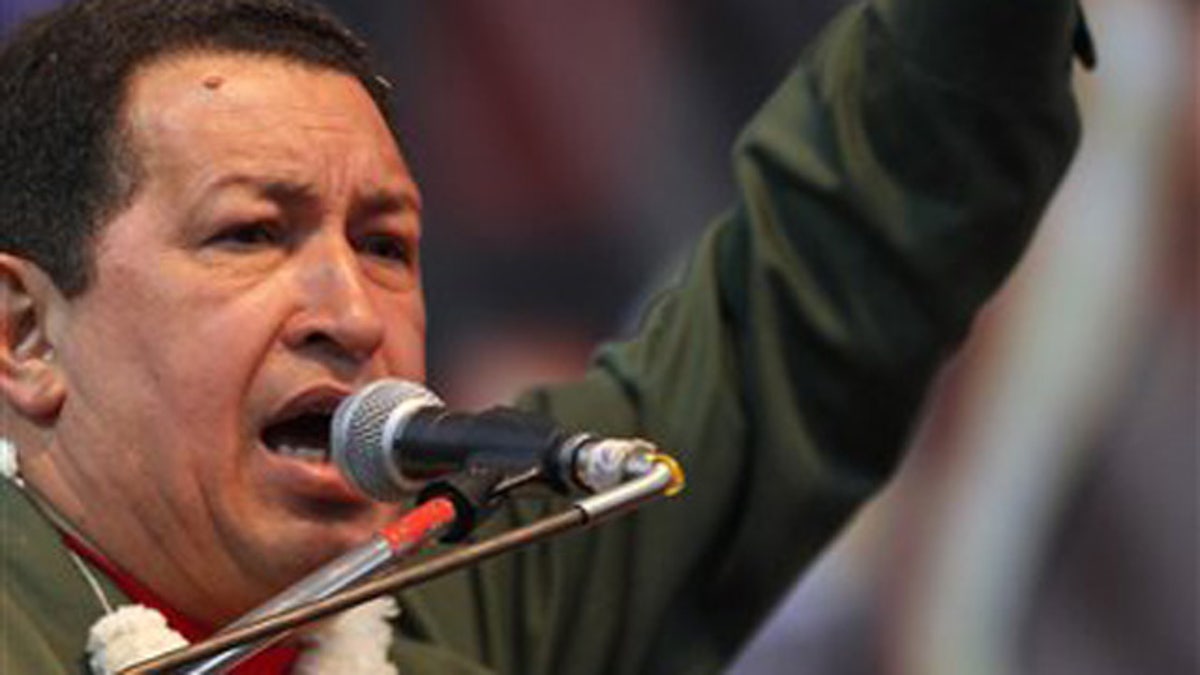

Venezuela President Hugo Chavez has little room to critique Arizona's new immigration law given the country's own record of human rights violations, experts told FoxNews.com. (AP)

On the heels of Mexican President Felipe Calderon's speech slamming Arizona's immigration law, Cuban leaders and Venezuela's president are adding to the chorus and calling the law 'racist and xenophobic" – but they're carrying their own human rights baggage.

Cuban parliamentarians passed a resolution last week denouncing Arizona's new law as "racist and xenophobic," as well as a "brutal violation of human rights." Venezuelan President Hugo Chavez, meanwhile, reportedly blasted the law through his minister of foreign affairs, demanding that it be "repealed" and that America move away from its "old habits of racism."

Foreign Minister Nicolas Maduro said immigrants in the U.S. are treated in a manner that's "inconsistent with human rights … a perennial violation against our fellow Latin Americans," CNSNews.com reported.

Ira Mehlman, spokesman for the Federation for American Immigration Reform, said those criticisms are misguided given the state of human rights in both Cuba and Venezuela.

"They're not fair and they are obviously politically motivated," Mehlman said. "Obviously, [Chavez and Cuban lawmakers] do not have the best interests of the United States at heart. They have appalling human rights records and their criticisms ought not to be taken seriously."

Cuba, the communist-run island of roughly 11 million, has long been condemned for its human rights record, including the jailing of roughly 200 political prisoners, the banning of a free press and the outlawing of opposition political parties. Cuban citizens also are mandated to carry identification at all times and can be stopped by authorities and sent home if they are found in a part of the island where they don't belong, the Associated Press reports.

"It's hypocritical of the worst dictatorship in the Western hemisphere to criticize Arizona's immigration law," said Alex Nowrasteh, an immigration policy analyst for the Competitive Enterprise Institute, a Washington-based conservative think tank. "Cuba's human rights record dealing with Hispanics is significantly worse than the United States in general, so perhaps they should clean up their own ship before they criticize others."

Nowrasteh said many Hispanics fled Fidel and Raul Castro's socialist state for the "supposedly racist and xenophobic" United States.

"They chose with their feet," he said.

Recent statements by Cuban politicians and Chavez are an attempt to connect with a "very small segment" of the American political scene that listens to what they have to say. He noted Chavez's usage of a Twitter account to reach the masses much easier.

"With modern technology, it's so much easier," Nowrasteh said.

But in a move characterized as optimistic, the Cuban government has agreed to move many of the country's political prisoners to jails closer to their homes and will provide medical care to some ailing prisoners, Cuba's Cardinal Jaime Ortega told the Associated Press on Sunday. It was unclear if all of the prisoners would be moved or how many would receive treatment.

One hunger-striking dissident, Guillermo Farinas, has refused food for at least 89 days, though he receives nutrients via a tube and has appeared strong and alert in recent phone conversations with the Associated Press. Another dissident, Orlando Zapata Tamayo, died in February after a lengthy hunger strike in jail.

Farinas, who began his hunger strike to protest Tamayo's death, has since said his main demand is better treatment for 26 political prisoners said to be in poor health, the Associated Press reports.

Meanwhile, in Venezuela, Chavez's human rights record has been criticized by watchdog groups in several areas, including political discrimination, lack of freedom of expression and freedom of association. The U.S. Department of State's 2009 Human Rights Report on Venezuela also identified other human rights problems in the country of roughly 27 million, including summary executions of criminal suspects, widespread criminal kidnappings for ransom, political prisoners and selective prosecution for political purposes, "considerable corruption" in all levels of government and many others.

The report also notes that Venezuelan law makes "insulting" the president a crime punishable by up to 30 months in prison without bail, with lesser penalties for insulting lower-ranking officials.

And while Venezuelan law provides for freedom of speech and of the press, the nation's combination of laws and regulations regarding libel and media content -- in addition to legal harassment and intimidation -- results in "practical limitations on these freedoms and a climate of self-censorship," according to the report.

Human Rights Watch, a New York-based watchdog group, detailed Chavez's first decade as president in 2008 in its 230-page report, "A Decade Under Chavez: Political Intolerance and Lost Opportunities for Advancing Human Rights in Venezuela."

"President Chavez has actively sought to project himself as a champion of democracy, not only in Venezuela, but throughout Latin America," the report read. "Yet his professed commitment to this cause is belied by his government's willful disregard for the institutional guarantees and fundamental rights that make democratic participation possible. Venezuela will not achieve real and sustained progress toward strengthening its democracy -- nor will it serve as a useful model for other countries in the region -- so long as its government continues to flout the human rights principles enshrined in its own constitution."

Jonah Goldberg, a visiting fellow at American Enterprise Institute, a Washington-based conservative think tank, said the recent comments are "standard operating procedure" for politicians in Cuba, as well as Chavez.

"The denunciation of the United States' human rights record comes from the people who have had the most brutal human rights record," he said. "It's the playbook they always go back to. Taking denunciations seriously from places like Cuba and Venezuela is just a colossal waste of time."

Goldberg accused Cuban lawmakers and Castro of making the most out of the United States' heated immigration debate following the signing of Arizona's law by Gov. Jan Brewer on April 23.

"The Arizona law feeds into a longstanding and long-simmering anti-American sentiment in certain parts of South and Latin America," he said. "Do [Chavez's and Castro's comments] get bigger play because of the climate? Sure, but that's sort of the larger point -- these guys are opportunists. They are going to try and seize the limelight and shape the agenda whenever they can."

The Associated Press contributed to this report.