ATLANTA – Authorities in Michigan's Genesee County were jubilant when Atlanta police arrested a suspect in a spate of serial stabbings that left five people dead. They weren't so thrilled about picking up the tab to get him back.

Extradition has long been a sore spot for sheriffs who contend state and federal authorities should pay more of the costs to return fugitives. Now economic troubles and budget deficits are forcing prosecutors and sheriffs to make tough decisions about who will face prosecution and who will remain free.

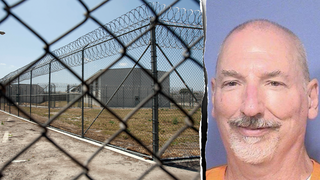

Returning the stabbing suspect, Elias Abuelazam, to Michigan to face multiple murder charges is expected to cost between $2,000 and $10,000 at a time when Genessee County has an $18 million budget deficit.

"We have to juggle with limited resources," said Genesee County Prosecutor David Leyton. "I have to do more with less, but so does just about everybody. We will do the job whether we get the extra help or not."

Officials said there was no question it was worth the cost in the case of Abuelazam, who is suspected in a string of 18 attacks in Michigan, Ohio and Virginia. He is expected to be extradited this week after his Aug. 11 arrest at Atlanta's airport.

But some authorities are now weighing the costs of extradition with the severity of the crime. Some lower-level offenders and suspects may not be extradited — which means they're set free.

John Morganelli, the district attorney of Pennsylvania's Northampton County, said detectives were once dispatched as far as California to pick up suspects in relatively minor crimes. He still extradites suspects in violent crimes, but he has drawn the line at lower-level misdemeanors such as probation violation or failure to pay fines.

"It doesn't make sense to spend more tax dollars to collect tax dollars that are owed," he said. "If it's a misdemeanor charge, a case where no great public harm is involved, we just can't go."

The risk is undermining the justice system when the resources don't exist to pursue all criminal offenders.

"County sheriffs are suffering immensely with extradition costs. And this isn't something to be taken lightly," said Aaron Kennard, the executive director of the National Sheriffs' Association. "If we don't extradite them, they never pay for the crime. If we don't go get them, we're thumbing our nose at the judicial system."

It's hard to quantify how many state or county prisoners are extradited each year from one jurisdiction to another. Federal authorities and the sheriffs association do not track the data, and several departments only ventured a rough guess. But Kennard said even small sheriffs' offices could extradite hundreds of people each year, while larger jurisdictions often ship thousands.

Each journey can be costly. Sheriff's offices or prosecutors often send two or three deputies or detectives to pick up suspects. With airfare, lodging and board, shipping a suspect hundreds of miles can cost $4,000 to $5,000. Some jurisdictions hire contractors that charge a per-mile fee.

It's typically up to prosecuting agencies to foot the tab to extradite prisoners, but in some cases their counterparts will chip in or offer other help because they are eager to unload suspects — and the daily costs of housing them.

Kennard said some sheriffs are asking their counterparts to ship the prisoner halfway to split costs. His organization is also trying to work out an arrangement with the U.S. Marshals Service to transport more county prisoners along with federal suspects.

Federal authorities have a national program that seeks to help counties ship some prisoners at a "minimal cost," said Bill Sorukas, a chief inspector with the U.S. Marshals. In fiscal year 2009, the program moved 1,208 prisoners who weren't in the federal system. That's just a fraction of the 350,000 federal prisoners moved the same time span.

Sorukas said there's only so much the system can do without more federal funding. Getting federal inmates to their court appearances remains the top priority.

Then-U.S. Sen. Joe Biden introduced legislation in 2008 that would have devoted more federal funding to help regional and local task forces extradite fugitives. But the legislation stalled and has yet to gain widespread support from lawmakers.

In the meantime, many sheriffs scramble to find creative solutions.

Navarro County Sheriff Les Cotten, for one, shrugged off the decision by the Texas county's lawmakers to slash his extradition budget from $75,000 to $5,000. That's because he's worked out an arrangement with a contractor to ship prisoners to his Texas county at a discount if he allows them to use his jail for other prisoners who stop along the way.

Prosecutors, too, are trying to rein in costs.

Derek Champagne, the district attorney in upstate New York's Franklin County, said his office only extradites smaller-scale white collar suspects if they are caught in neighboring states.

"In any crimes we have victims, we absolutely spare no expense," he said. "But if it's welfare fraud or some sort of white collar crime and it's not over $10,000 we will put 'adjoining states only' on the warrant. So if someone's in Florida and it was a $5,000 fraud, we're not spending $3,000 or $4,000 to get him."

Every decision not to extradite is risky.

One example is the case of Maximiliano Silerio Esparza, an illegal immigrant who was captured by U.S. Border Patrol agents in 2002. Oregon officials had an old marijuana charge on Esparza but declined to extradite him. He was driven back to Mexico and released.

Seven months later, after he made his way back to Oregon, he raped two nuns and killed one of them as they walked and prayed on a bike path. He pleaded guilty in April 2003 and was sentenced to life without parole.

Ed Caleb, the district attorney of Oregon's Klamath County who put Esparza away, said the debate over extraditions puts prosecutors in a bind.

"It's a funny way of practicing law," he said. "There's some people that aren't dangerous that you wish would go to another state, and you don't extradite them back on the hopes that you don't have to see them again."

Morganelli, the Pennsylvania prosecutor, said he knows there's a chance some suspects could one day commit a more serious offense.

"We do worry about it," he said. "But we just don't have the bucks, so we can't go. I try to make sure we're protecting the public the best we can. You just never know what can happen."

___

Associated Press Writer Corey Williams in Detroit contributed to this report.