ARROYO HONDO, N.M. – Whose land is it anyway?

Private homeowners in Northern New Mexico have found themselves in the middle of a legal dispute dating back to colonial times after discovering they've been living on a Spanish land grant that may belong to a group of rightful heirs.

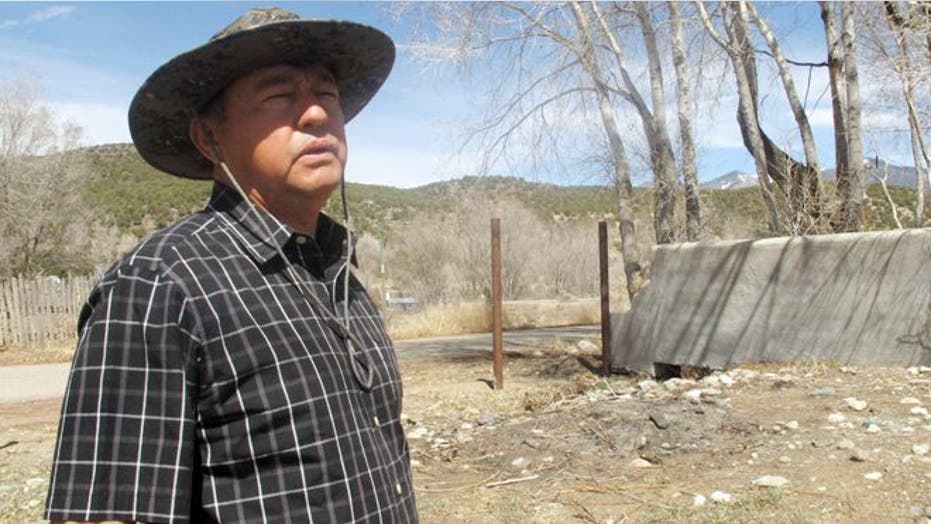

Fernando Martinez is among hundreds who finds himself in the middle of the legal quagmire.

Martinez's family has lived on the Arroyo Hondo Land Grant for more than two centuries, passing property from generation to generation in the popular area near Taos.

For the past couple of years, though, it has become impossible for Martinez or hundreds of others with homes in the mountainous northern New Mexico enclave to do much of anything with their properties.

- Unemployment Rate In Spain Hits Record 27.2%, Leaving More Than 6 Million Jobless

- Urdangarín, Husband Of Spain’s Princess Cristina, Accused Of Corruption

- Las Fallas Festival Kicks Off in Spain

- Spain’s King Juan Carlos Leaves Hospital After Spine Operation

- Budget Travel: Catalunya, Spain

- Queen Letizia’s Style Taking Spain By Storm

The 31-square-mile land grant, parceled out by the Spanish monarchy in the early 19th century to encourage settlement of the then-remote region, is at the heart of a bitter legal tug-of-war that has thwarted property owners' efforts to sell or refinance their homes, or even buy insurance policies, while pitting frustrated neighbors against each other.

"It's a mess," said Martinez, 66, a retired miner who couldn't obtain a title to house he wanted to purchase. "We can't do anything. It's like we're stuck in time."

The dispute began in 2010 after the Arroyo Hondo Land Grant Board filed a warranty deed with the Taos County Assessor's office in an attempt to reclaim 20,000 acres of private land originally granted to Arroyo Hondo's founding families. In the deed, the five-member board claimed that the Spanish land grant belonged to board members and heirs with blood ties to the originally Hispanic settlers, some of whom later became victims of white land speculators who were allowed to roam free after the U.S.-Mexican War.

"What you're dealing with is colonial history and land grabs as a result of conquest," said Santiago Juarez, the board's attorney. "It's not easily resolved."

That may be true, some homeowners say, but they believe the deed filed in the county assessor's office is bogus and didn't have the approval of most heirs. In fact, Martinez said the Arroyo Hondo Land Grant Board is controlled by one family that has often clashed with other heirs.

No phone number was listed for Lawrence Ortiz and Leandro Ortiz, two brothers and board members behind the deed filing. No one answered the door to an address listed for Lawrence Ortiz.

Pennie Herrera Wardlow, an Arroyo Hondo heir and a real estate agent in Taos, N.M., learned of the dispute after she sought to lower her interest rate and reduce her monthly payments from $1,200 a month to $700. But she couldn't do the refinancing because underwriters are too leery given the uncertainty over the dispute.

"They are hurting the very people that they say they want to help," said Wardlow. "I haven't been able to do anything for two years now."

The uncertainly also has hurt real estate in trendy Taos just as the area was just starting to recover from the economic downturn, said Paul A. Romero, a broker. He said around 3,000 properties within the land grant boundaries have been affected.

"This comes at a bad time," Romero said. "We're up 30 percent overall but people can't buy or sell in Arroyo Hondo."

Unique to Spanish colonial territories in the American Southwest, land grants were awarded to settlers by the Spanish government to encourage settlement in the empire's northern territories, which were difficult to control due to it being far removed from Mexico City. The area was also populated by American Indians, some of whom were hostile to European, and later Mexican, settlers.

The Arroyo Hondo Land Grant fight is just the latest in a string of similar battles that began in the 1960s when former preacher Reies Lopez Tijerina organized heirs to various land grants in New Mexico after years of the issue being ignored. He contended that the U.S. government stole millions of acres from Hispanos — the term used in New Mexico — following the signing of the treaty that ended the Mexican War in 1848. The United States pledged in the treaty to respect private land holdings, including land grants made under the Spanish and Mexican governments.

In 1967, Tijerina and followers raided the courthouse in Tierra Amarilla, N.M., to attempt a citizen's arrest of the district attorney at the time after eight members of Tijerina's group had been arrested over land grant protests. During the raid, the group shot and wounded a state police officer and jailer, beat a deputy and took the sheriff and a reporter hostage before escaping to the Kit Carson National Forest.

The raid sparked excitement among Mexican-American college students who identified with Tijerina's message of Latinos getting displaced and led to years of court battles around land grant claims.

Since the Tierra Amarilla courthouse raid, the land grant movement has become more widely accepted, and even gets its own day from New Mexico state lawmakers during legislative sessions. That's probably why courts closely examine all land grant claims "no matter how ridiculous they may be," said David Correia, author of "Properties of Violence: Law and Land Grant Struggle in Northern New Mexico."

"Someone making unsubstantiated claims can really disrupt titles in New Mexico," Correia said. "It shows the conflicts of property ownership that still exist in northern New Mexico."

Typically, land grant claims lose in court, he said.

Meanwhile, Arroyo Hondo heirs say they are bracing for months, if not years, of more court fights. In February, a district judge ruled that the deed filed by the Arroyo Hondo Land Grant Board had no legal basis since it did not create nor transfer any interest in real property. The judge ordered an attorney representing heirs who filed a lawsuit against the board and three title companies to draft the order.

Juarez disagreed with the order and the other attorney asked for another hearing, saying it's "far from over."

Based on reporting by The Associated Press.

Follow us on twitter.com/foxnewslatino

Like us at facebook.com/foxnewslatino