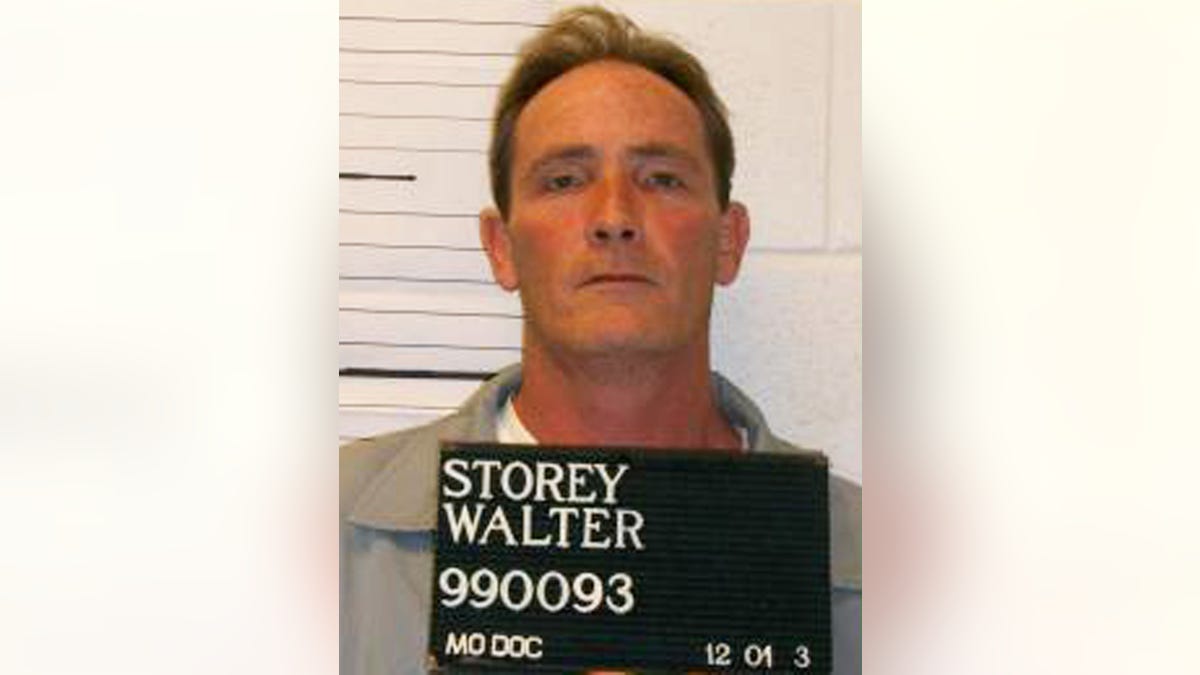

Feb. 10, 2015: In this Jan. 1, 2012 photo provided by the Missouri Department of Corrections is Walter Storey of St. Charles, Mo., who faces the death penalty for killing Jill Frey in 1990. (AP)

ST. LOUIS – A Missouri inmate hours away from execution claimed in an appeal to the U.S. Supreme Court on Tuesday that the lethal drug could cause a painful death.

Walter Timothy Storey is scheduled to die at 12:01 a.m. Wednesday for killing a woman who was his neighbor 25 years ago in the St. Louis suburb of St. Charles. After a Missouri-record 10 executions in 2014, it would be the state's first this year.

Missouri obtains its execution drug, pentobarbital, from an unnamed compounding pharmacy, and prison officials refuse to disclose details about how or if it is tested. Storey's attorney argues that the secrecy makes it impossible to know if the barbiturate will quickly work or cause an unconstitutionally painful death.

"After all, compounding is not necessarily a matter of changing a drug's flavor, but rather it is a matter of combining different ingredients in new, untested ways," Storey's attorney, Jennifer Herndon, wrote.

She cited an anesthesiologist who said that that "sub-potent pentobarbital" could severely disable the prisoner without killing him, potentially leaving him alive but permanently brain-damaged.

In a response, the Missouri attorney general's office noted that virtually every recent inmate facing execution has raised the same issue.

"A dozen Missouri executions using pentobarbital have been rapid and painless," the response read.

Herndon also expressed concerns about Missouri's use of the sedative midazolam prior to executions. The state has said the drug is administered to help calm the nerves of inmates, and only to those who want it.

Herndon wrote that midazolam was used in three botched executions in other states in 2014.

Storey, 47, was sentenced to death three separate times in the same case.

He was living with his mother in a St. Charles apartment on Feb. 2, 1990, when he became upset over his pending divorce. He spent an angry night drinking beer.

He ran out of beer and money, so he decided to break into the neighboring apartment of Jill Frey to steal money for more beer.

Frey, a 36-year-old special education teacher, had left the sliding glass door of her balcony open. Storey climbed the balcony and confronted Frey in her bedroom, where he beat her. Frey suffered six broken ribs and severe wounds to her head and face.

Storey used a kitchen knife to slit her throat so deeply that her spine was damaged. Frey died of blood loss and asphyxiation.

Storey returned the next day to clean up blood, throw clothes in a trash bin and scrub Frey's fingernails to remove any traces of his skin.

But he missed a key piece of evidence: blood on a dresser.

"There was a really good palm print in blood," said Mike Harvey, a retired St. Charles detective who now works as an investigator for the St. Charles County prosecutor.

Lab analysis matched the print to Storey, whose prints were on file for a previous crime.

Storey was convicted and sentenced to death.

The Missouri Supreme Court tossed the conviction, citing concerns about ineffective assistance of counsel and "egregious" errors committed by Kenny Hulshof, who was with the Missouri attorney general's office at the time and handled the prosecution. Hulshof was later a congressman and a candidate for governor.

Storey was tried again in 1997, and sentenced again to death. That conviction was also overturned, this time over a procedural error by the judge. Storey was sentenced to death a third time in 1999.

Herndon said Storey is remorseful for his crimes and has spent "thousands of hours" working in a restorative justice program in prison, trying to help crime victims.