US seaports develop new strategies to fight drug trafficking

Law enforcement officials say drug dealers have flooded cocaine, fentanyl and methamphetamines into the Port of Philadelphia at an alarming rate.

The Port of Philadelphia, a nondescript shipping facility tucked in between Pennsylvania and New Jersey, is known for its imports of perishables like produce, meat, and dairy. But in recent years, to the chagrin of law enforcement officials, it’s become known for something else: a major drug destination.

Law enforcement officials say cocaine, fentanyl and methamphetamines are pouring into the cargo port at an alarming rate. A recent bust at the Philadelphia port by Customs and Border Protection, which found 700 pounds of cocaine hidden in a furniture shipment from Puerto Rico, underscores the disturbing new trend.

The Area Port of Philadelphia is known as niche port for perishable goods.

"One of the things we've noticed at the [Drug Enforcement Administration] is the amount of cocaine that has been imported to the area has greatly increased,” said DEA Special Agent Patrick Trainor.

Within the last decade, the Customs and Border Protection, the agency that oversees the ports, has reported major drug busts at the Philadelphia port beginning in 2007, with a seizure of 864 pounds of cocaine, 386 pounds in 2012, 363 pounds in 2015 and, most recently, 709 pounds in 2017, which was the sixth largest cocaine bust in port history.

A recent bust at the Philadelphia port by Customs and Border Protection found 700 pounds of cocaine hidden in a furniture shipment.

And that’s just the amount of drugs federal agents are finding.

The DEA says in the last year the amount of cocaine in the area – and in ports all across the country – has increased because drug traffickers are changing their distribution methods.

With the U.S. tightening its border with Mexico and Canada, and airports becoming more sophisticated in capturing illegal shipments, dealers are looking at U.S. ports as the newest conduit to smuggle their product.

“We are not exactly surprised to hear that 700 pounds of cocaine were removed from the port,” Trainor said. “Last year alone, more than 63,000 people died from drug-related overdoses in the U.S. That’s more death than the entire Vietnam conflict.”

Decades ago, traffickers used the “Caribbean corridor” to ship drugs – a pipeline that moved drugs from South America through Central America and the Caribbean to ports along the East Coast. But after the fracturing of the Colombian drug empire, dealers began moving drugs through the porous Mexican border.

But now, for a variety of reasons, including stepped up enforcement at the border, dealers are going back to using the Caribbean corridor and using ports to smuggle their illegal shipments.

“The U.S. was never really able to close the Caribbean corridor,” said Stratfor, Security and Terrorism analyst Scott Stewart. “And over the last couple of years, things have gotten chaotic in Mexico. So, in response, we’ve seen a shift back to traditional trafficking routes of the 1970s.”

The shift in tactics represents a growing field of lucrative opportunities for smugglers – and has law enforcement officials scrambling to play catch up.

“There’s no silver bullet to catching a drug smuggler,” says Edward Moriarty, Customs and Border Protection's acting director for the area port of Philadelphia.

Moriarty said dealers are taking advantage of existing supply chains and using legitimate shipments to keep their illegal drugs flowing into the country. And as soon as law enforcement officials create new technology to curb the drug flow, traffickers find a loophole.

U.S. Customs and Border Protection's advance x-ray technology scans imports at the Area Port of Philadelphia.

“It’s sort of like a cat and mouse game,” Moriarty said. “But that’s where technology comes into play. We are constantly updating our X-ray systems, cameras, and advance intelligence."

Not only do large shipments pose a threat to Philadelphians, the city’s proximity to wide-scale cocaine markets like New York, Pittsburgh, Youngstown, and Cleveland increase its vulnerability.

“Every port, not just Philadelphia, is susceptible to smugglers, and drug dealers will use any means, person, or condition to sneak contraband into the U.S.,” Moriarty said.

Experts believe that corruption, not physical security, is among the greatest risk.

“These organizations see bribing people to get the shipments through as an answer to increased security,” says Stewart.

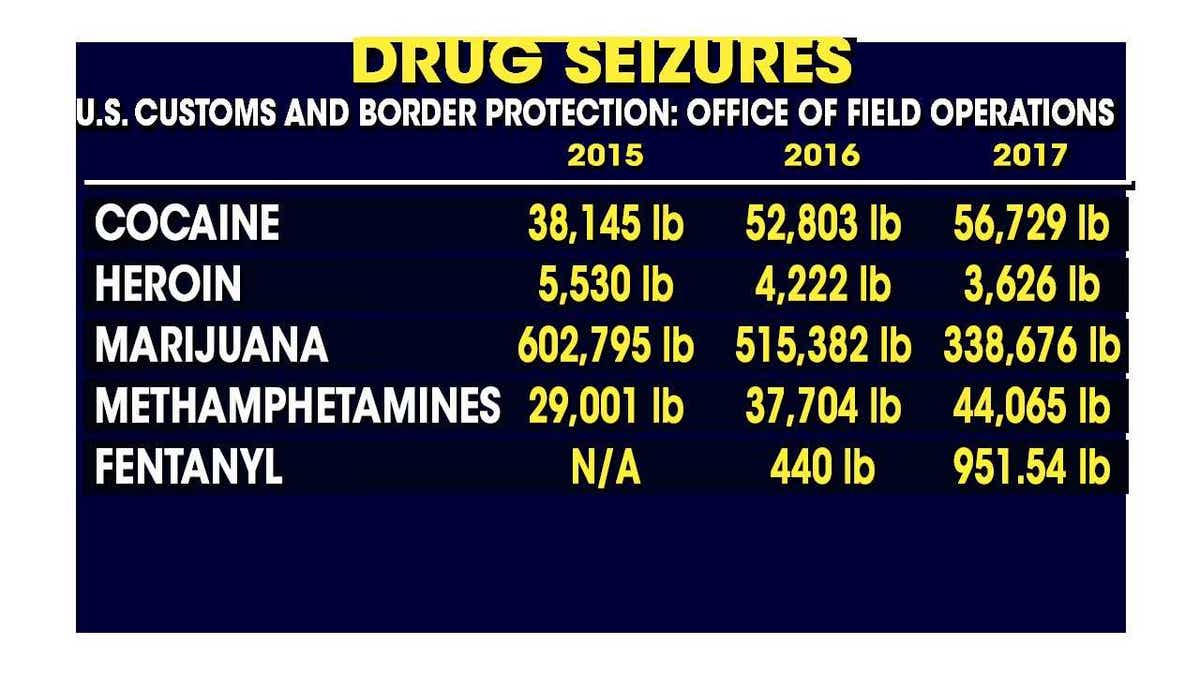

Last year, the USCBP’s Office of Field Operations made record-high drug seizures, finding 56,729 pounds of cocaine, 44,065 pounds of methamphetamines and 951 pounds of fentanyl, which more than doubled since 2016. Law enforcement officials are on pace to also break records in 2018.

The force driving the market, Stewart said, is both supply and demand.

“As long as the U.S. is willing to pay these large amounts of monies for these substances,” Stewart said, “creative traffickers will find a way to meet that demand.”