Man sent to prison by anti-death penalty group speaks out

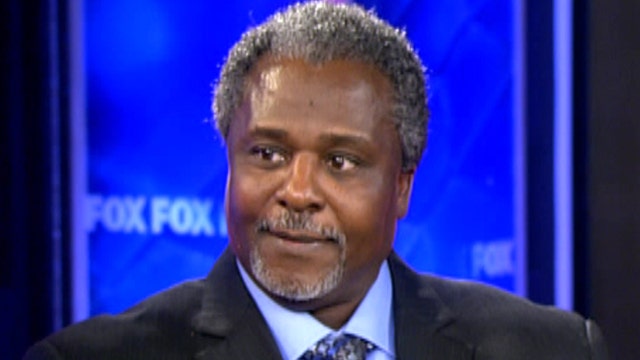

Alstory Simon opens up about his time in prison and trying to forgive those who put him there

Alstory Simon has always considered himself a forgiving person, but after being tricked into confessing to a double murder and spending 15 years in prison, he finds it hard to turn the other cheek.

In a case fraught with irony, Simon's bitterness is directed at the Medill Innocence Project, an advocacy group dedicated to freeing innocent people. It was that group that he, and now prosecutors, accused of using threats, trickery and false promises to get a crack-addled Simon to say he killed two teens in a Chicago park in 1982. The confession of Simon led to his conviction and death sentence, but it also freed another man from death row and prompted Illinois to end capital punishment -- ultimately sparing Simon himself from execution.

“It was very hard to get along with knowing that fact: that I was locked up in prison for something I knew I didn’t do,” said Simon, now 64, who walked out of prison last month after the Cook County State's Attorney vacated murder charges and blasted the tactics of the Medill Innocence Project. “It can make you kind of mean, but as time went by I overcame it.

“I was praying every day, asking God to shine down upon me,” he added.

[image]

The Medill Innocence Project, a legal advocacy group once affiliated with Northwestern University and patterned after the Innocence Project, was established in 1999 to reinvestigate murder convictions in Illinois. It has been credited with freeing 11 innocent men from death row and playing a key role in the state's 2003 decision to suspend executions. One of those men was Anthony Porter, who was originally convicted and sent to death row for the murders of Jerry Hillard and Marilyn Green. Porter had served 15 years on death row when the Medill Innocence Project came to believe Simon was the real killer.

[pullquote]

Members of the group, which was led by former Northwestern University Journalism Professor David Protess and included several students and a private investigator, confronted Simon in his home in 1999, telling him the mother of one of the victims had placed him with Porter at the scene and telling him they were working on a book about the murders.

“The Innocence Project had bum-rushed my house and accused me of murder,” recalled Simon, who was battling a drug problem at the time.

Simon denied any involvement in the murders, but the group persisted. Days later, it sent private investigator Paul Ciclino and another man to Simon's home, with both flashing guns and Chicago Police Department badges. They urged Simon to confess if he wanted to avoid the death penalty, according to Simon.

They promised Simon a light sentence and royalties from book and movie deals, and showed him video of his ex-wife, Inez Jackson, and another man who proved to be an actor claiming they saw Simon kill the pair, according to Simon.

Worn down and on drugs, Simon says he gave the Medill Innocence Project the videotaped confession it wanted. But he only relented after the group used the very tactics it had often accused police of employing, according to Simon's attorney, Terry Ekl.

“They did everything that’s forbidden by the law enforcement community,” Simon said. "These people went to great lengths to do what they did to me, and I never did anything to anyone.”

[image]

The admission played a key role in the overturning of Porter's conviction and release in 1999, just two days before he was to face death by lethal injection, but it meant hard time for Simon, who was convicted of the murders and sentenced to 37 years in prison. If it were not for a moratorium on executions in effect during his trial, Simon would have faced execution.

But Simon has supporters of his own, who believed in his innocence. They went to court, produced a documentary and ultimately convinced prosecutors to re-open the investigation into his case more than a year ago. Anita Alvarez, the State’s Attorney for Cook County, determined Simon's confession was false and vacated the charges against him. On Oct. 30, a judge ordered his immediate release.

“At the end of the day and in the best interests of justice, we could reach no other conclusion but that the investigation of this case has been so deeply corroded and corrupted that we can no longer maintain the legitimacy of this conviction,” Alvarez said.

Neither Protess nor the Medill Innocence Project, now known as the Medill Justice Project, returned calls for comment.

But the man who went to prison because of their discredited efforts is enjoying his newfound freedom and trying to check his bitterness.

“It was like something that stepped completely out of me,” Simon recalled when he was released. "It’s like when you have a big weight on your back and all of a sudden my body just got light,” he said. “I started jumping for joy.”