Bugundy-trained Michael Shaps-- owner of Wineworks located in Albemarle County, VA. -- is part of a new generation of Virginia winemakers putting an emphasis on quality. (Michael Shaps Wineworks)

Virginia isn’t necessarily on every wine lover’s radar. But maybe it should be.

The East Coast upstart is now the nation’s fifth largest wine producer (only California, Washington, New York and Oregon make more) and fifth in the number of wineries (275 and counting).

“The best Virginia wines are underpriced compared to what’s out there in the world.”

And while most of the wine made in Virginia is still consumed in state, a handful of standouts are achieving national and international recognition. The last decade has seen a wine boom in the Old Dominion, as the industry draws international talent and money—and some critical acclaim.

But whether Virginia can provide real bang for your wine dollars—and if state’s winemakers can move consumption out of their picturesque tasting rooms to retail shelves and kitchen tables-- still remain to be seen.

“I think the path that Virginia is on—for the first time-- is clearly defined, ambitious, terrific but it’s only at its beginning,” says wine writer and educator Karen MacNeil, whose classic guide “The Wine Bible” is slated to be released in an updated second edition in October.

“The good part is that there’s a lot of talent and ambition and some money now in Virginia, and none of those things were ever as true in the past as they are right now,” MacNeil says.

Virginia has a history of viticulture that dates back to Thomas Jefferson, who attempted (with little success) to grow wine grapes on his central Virginia estate, Monticello. The Mid-Atlantic’s cold winters and humid summers proved to be a tough stumbling block for early growers, followed by what MacNeil describes as a “wrong turn” in the early 20th century as growers experimented with hybrid grape varietals (blending classic European wine grapes with native American varietals) in an effort to make grapes more resistant to pests and disease.

But a slow turnaround started in the 1970s as Europeans, like Italian winemaker Gianni Zonin, entered the picture. Zonin, who is one of Europe’s largest wine producers and owner of several Italian wineries, bought Barboursville Vineyards near Charlottesville, his only U.S. property. In 1976 he began planting European vinifera grape varietals. In the 80s, influential winemakers like Linden Vineyards’ Jim Law and Horton Vineyards’ Dennis Horton -- followed suit and began successfully experimenting with French varietals from Bordeaux and the Rhone Valley rather than old school hybrids like chambourcin and vidal blanc.

By 1995, Virginia had 46 wineries. And after two decades of trial and error by industry pioneers, the 1990s were a watershed decade for the state, says Virginia Wine Board director Annette Boyd, as winemaking began to shift from hobbyists to professionals, and European varietals took hold. Now 80 to 85 percent of Virginia wines are now made with European-style vinifera grapes, Boyd says. “That’s where you get critical acclaim and that’s where you get consumer interest.”

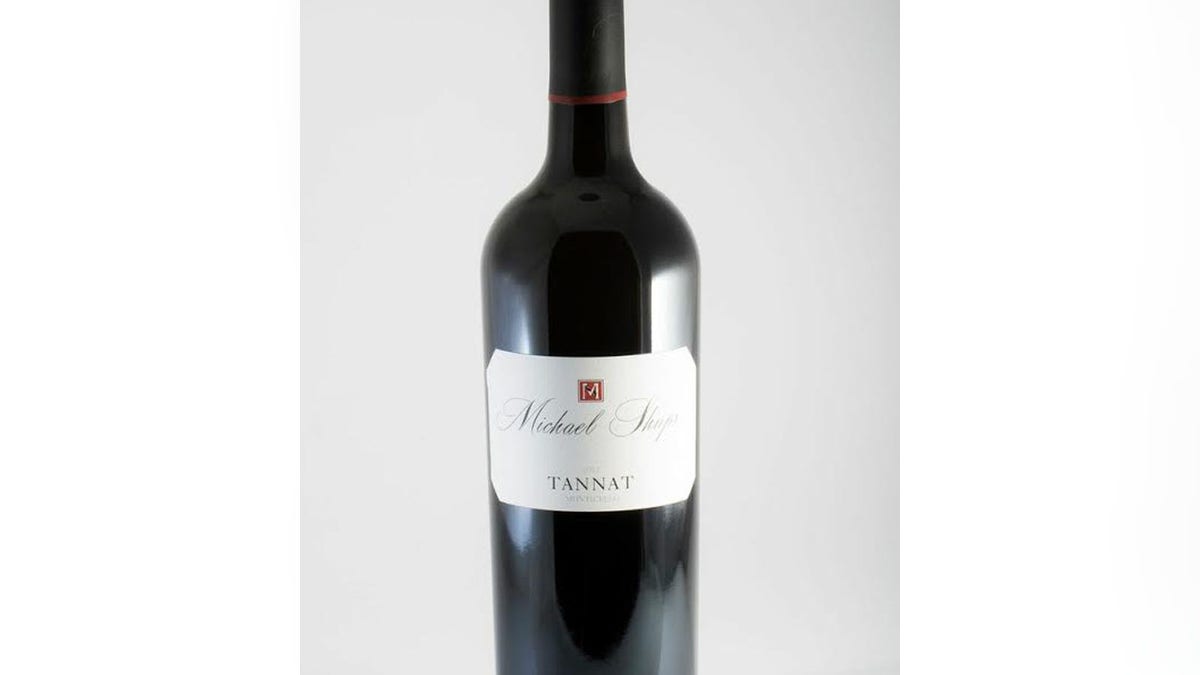

Michael Shaps’ award winning tannat, made from a little known grape grown in southern France, has impressed critics like Karen MacNeil. (Michael Shaps Wineworks)

It was the boomlet in the 90s that attracted the attention of one of the state’s rising stars Michael Shaps— owner of the Virginia Wineworks label, as well as the nationally recognized, Michael Shaps label. Back then, the New York native was training as a winemaker in France’s legendary Burgundy region when word of Virginia’s boom made its way across the Atlantic. For Shaps, who was used to Burgundy’s unpredictable climate, the challenge of Virginia’s seasonal climate (generally considered to make for tougher growing conditions than those on the West Coast) was part of the appeal.

“I always prefer to take a little bit of the harder way,” he says. “The East Coast was closer to what I experienced in France.”

Shaps, 51, opened his winery in the picturesque region near Charlottesville in central Virginia in 2007. Shaps doesn’t own vineyard land and instead relies on a network of long-term leases across the state. This allows him to integrate the French concept of terroir (the idea that the place where the grapes are grown—including soil and climate—gives a wine its unique characteristics) and plant grape varietals in places they’ll grow well.

Virginia now has seven AVAs (American Viticultural Areas), giving regions their own winegrowing identity similar to California’s Napa and Sonoma regions. It’s a sign of the state's growing maturity as a wine region. And much as the Napa Valley found its niche in cabernet sauvignon, finding the right varietals will be key to Virginia’s success, MacNeil says.

Shaps and other leaders continue to experiment with European varietals—including some unexpected and little known grapes like the tannat and petit manseng varietals grown in southern France (Shaps’ wines made from those two varietals were winners in the Virginia Wineries Association’s 2015 Governor’s Cup competition). The red cabernet franc grape (grown in Bordeaux and the Loire Valley) and the white viognier varietal (grown in France’s Rhone Valley) have also had success in Virginia.

Then there’s the price question. The relatively small size of most Virginia vineyards and higher land and labor costs mean Virginia will never really be able to compete in the $10 and under category, Boyd says, but “Virginia wines compete and they compete extraordinarily well” in the $15 to $20 category.

Shaps’ award-winning tannat retails for $40, and the big winner of this year’s Virginia Governor’s Cup-- Muse Vineyards' Bordeaux-style blend-- retails for $45. Those numbers pale in comparison to a high-end Napa wines but seem pricey compared to many highly rated European wines available on retail shelves.

MacNeil says Virginia wine prices genuinely reflect the cost of doing business—especially in a region without a strong history of viticulture.

“Wine in the U.S. in general is expensive. It’s also true of California. In many cases you can get an old world version for much less. That’s a somewhat intractable problem…It’s just expensive to do business in the United States,” she says.

And Shaps argues that while many Virginia wines haven’t reached the level of quality found in other areas, the best ones are actually a bargain.

“The best Virginia wines are underpriced compared to what’s out there in the world.”