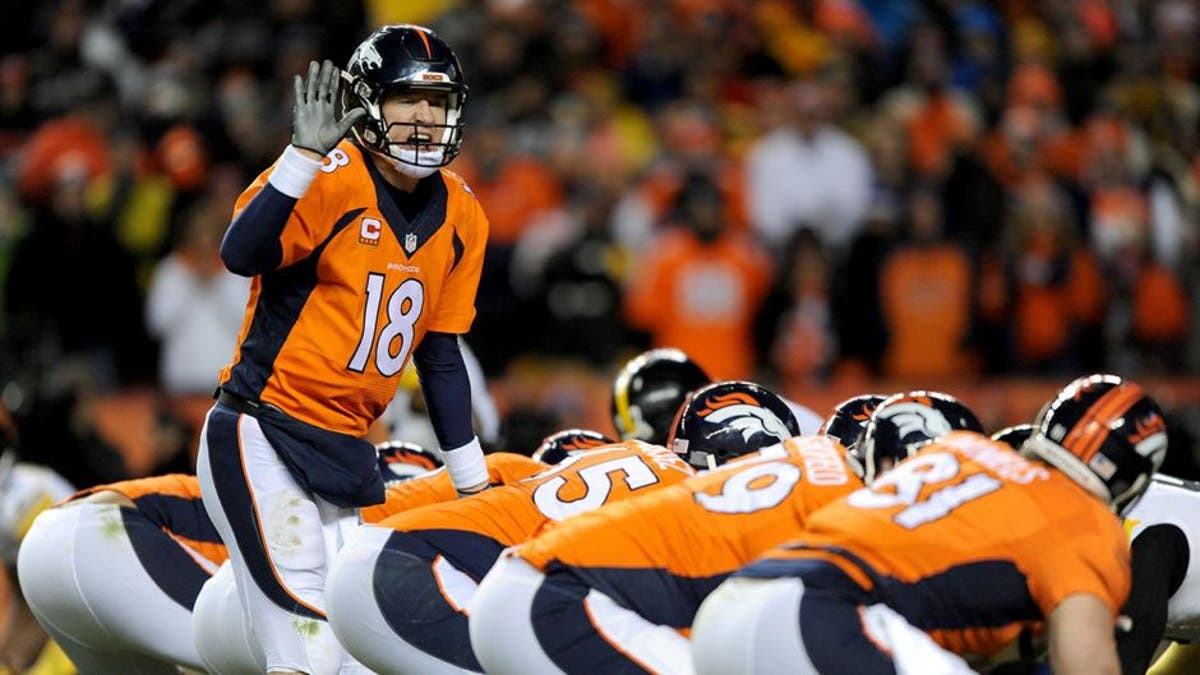

DENVER, CO - JANUARY 17: Peyton Manning #18 of the Denver Broncos calls a play against the Pittsburgh Steelers during the AFC Divisional Playoff Game at Sports Authority Field at Mile High on January 17, 2016 in Denver, Colorado. (Photo by Dustin Bradford/Getty Images)

Whenever I think of Peyton Manning, one of the first things that comes into my mind is The Folder. It looked like it would've fit into one of those old Trapper Keepers from the '80s. This one looked that old. It was bright orange and weathered. It had the name MANNING scribbled across the front.

LSU's longtime strength coach Tommy Moffitt first showed me The Folder three years ago. He pulled it out of a drawer from his desk on my trip to Louisiana. I was there to work on my quarterbacks book and the Manning Passing Academy was about to start a couple hours down the road later that day. After all, how do you do a book about QBs without visiting the Mannings?

Moffitt, the strength coach at Tennessee when Manning was the Vols star QB in the mid-'90s, had shown all Tiger freshmen when they reported to school this frayed old folder that contained pages of the workouts he'd prescribed for the quarterback during the summer going into his senior season.

Inside, the printed sheets of paper were covered with notes Manning had jotted down, showing the player's attention to detail and indefatigable level of preparation. There were some crossed-out poundages of prescribed workout routines where Manning pushed himself to do five or 10 pounds more than Moffitt had anticipated. Everything was accounted for and documented with check marks and pluses along with margin notes such as Threw good outside 1 on 1 ... 7x Hills Threw ... Agilities/Sand.

Moffitt told all his newcomers at LSU that he had never -- in 25 years -- seen anybody as meticulous in their preparation as Peyton Manning. The weathered orange folder was Exhibit A, an artifact worthy of its place in Canton once Manning took his place in the Pro Football Hall of Fame.

"I tell them all, 'Right now, you're a better athlete than Peyton Manning ever was or Peyton Manning ever will be," Moffitt said. "But this -- THIS! -- is what makes him so special. His preparation and his attention to detail and the things he does that nobody else told him, that, 'This is what you have to do to be great.'"

Moffitt's favorite highlights of Manning's career didn't take place in Neyland Stadium. They happened around the Vols' football complex at odd hours, when almost no one else was around. Such as the time Moffitt heard a tap on the window to his office. Manning was outside. He needed help. Said he had a bunch of VHS tapes in his SUV that needed to go upstairs. Moffitt came outside to Manning's old black Oldsmobile Bravada and did a triple take when the senior quarterback opened the trunk.

It was jammed with tapes of every practice, every game, every opponent. Tight copies. Wide copies. End zone copies. Four years of film study. The ingredients to Manning's secret sauce. They ended up with two full shopping carts and kept unloading and filling.

Or the time Moffitt watched from his office window a 19-year-old Peyton tying a surgical cord to a goalpost and the other end around his waist so he could work on his drops from center. Back and forth, back and forth, for what seemed like hours. Moffitt had never seen any other quarterback do that, and certainly not on his own without any coaches or teammates around.

"Nobody here told him to do that," Moffitt said. "Maybe Archie did."

Nope. It wasn't Archie's idea, either, according to the head of America's First Family of quarterbacks.

"I didn't lead him there," Archie Manning told me. Then again, he kind of did, in a roundabout, Peyton sort of way.

"Peyton told me once he wanted to be a good player," Archie said. "I told him the good players I know work at it. That's all I told him."

That was Peyton Manning, always figuring out a way on his own to get better. Moffitt said that was why the guy would be a first-ballot Hall of Famer. It was also a big reason why more than 1,200 kids and some two dozen college QBs made the trek down annually to the Manning family's week-long camp in stifling humidity in Thibodaux, Louisiana.

By the way, the camp was also Peyton's idea, Archie said. Peyton, then a young quarterback at Tennessee, noticed the high school box scores in the newspaper, with teams getting blown out and their QBs going 1-for-4. Peyton wanted to have a camp to boost the level of quarterbacking in the local high schools.

That first year, the Manning Passing Academy was held at Tulane University and had 180 campers. There were three college counselors helping out: Peyton, Jake Delhomme from what was then called Southwestern Louisiana, and his receiver, Brandon Stokley. Peyton's baby brother, Eli, was a high school camper.

It didn't take long for the MPA to outgrow the place, shifting to Southeastern Louisiana before relocating to the Nicholls State campus in 2005. Since then everyone from Andrew Luck to Russell Wilson has attended.