Veterinarian fights for right to give pet advice online

Jeanne Zaino and Lee Carter discuss legal battle over telemedicine

When a woman in Turkey had an iodine-deficient cat and needed help coming up with a pet-food recipe, she turned to Ron Hines. When an aid worker in Nigeria needed medical advice for the cat she and her husband brought from Scotland, she, too, turned to Hines.

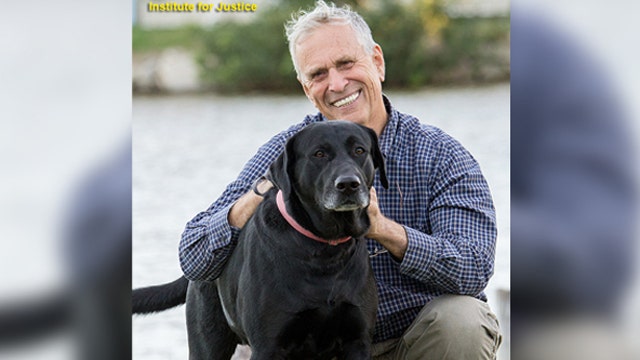

A licensed veterinarian living in Texas, Hines has given advice to hundreds of pet owners like them over the course of a decade. But for these informal consultations, Hines was fined and reprimanded and had his license suspended in 2013.

The problem? Hines was offering that advice online, communicating remotely with pet owners across the country and around the world.

The state of Texas said that was a no-no.

The dispute has landed Hines at the center of a legal battle that could go all the way up to the Supreme Court. His case is part of a growing national debate over online medicine, a practice known as "telemedicine." As virtually every profession goes online in some way, the medical field is still dealing with immense legal questions over to what extent doctors -- and veterinarians -- can give advice, offer a diagnosis or even prescribe medicine online.

'Texas thinks it’s better that these people and their pets get nothing, rather than have [an online] conversation with a very accomplished veterinarian'

The Institute for Justice, which is representing Hines in court, argues that Texas laws in this case are effectively preventing people in remote locations from getting hard-to-find medical advice.

“Texas thinks that if a veterinarian doesn’t see an animal and owner in person, he completely loses his ability and professional judgment,” said Jeff Rowes, senior attorney for the Institute for Justice, charging that Hines' First Amendment rights are at stake.

“Texas thinks it’s better that these people and their pets get nothing, rather than have [an online] conversation with a very accomplished veterinarian.”

Hines, 71, challenged his 2013 suspension and $1,000 fine in court and initially won. That ruling was overturned in March by the 5th Circuit Court of Appeals, which said Hines had clearly violated rules from the Texas State Board of Veterinary Medical Examiners, which states that in order to treat an animal a vet must have an established veterinarian-client-patient relationship, achieved only through a physical exam and not via telephone “or other electronic means.”

Hines’ case has stoked the debate over whether advancements in technology can allow practitioners to help patients remotely. On the veterinary side, the laws are fairly strict nationwide, said Dr. James Wilson, a veterinary law and ethics professor at Iowa State University. He said no state would have allowed Hines to dispense professional advice remotely.

“He would have run against the same problem in every state in the USA,” he told FoxNews.com, “because those laws are uniform about what constitutes an acceptable physical examination in the veterinarian-pet relationship.”

The idea behind the rules is to prevent potentially uninformed and dangerous medical advice. Wilson believes, as did the 5th Circuit, that the state’s interest in regulating the profession comes before the First Amendment. “Is this about free speech, or is this [activity] so risky that the consuming public could really be misled by someone who is erroneously making diagnoses, prescribing treatment to the owner of an animal, without any recourse for the recipient of that information?”

For Wilson, the answer is clear. The “risks of erroneous, incompetent information far outweigh the benefits” of telemedicine as it stands now, he said.

But telemedicine defenders disagree.

In Hines' case, he was hardly the kind of quack whom telemedicine skeptics worry about. He technically retired in 2002 after a lengthy career in veterinary medicine, working in both direct practice and in research at the National Institutes of Health. A broken back during work with a monkey colony decades ago, however, had left him partially disabled.

After his retirement, he launched his website as a forum for cat and dog owners. He began offering advice, most of the time for free or a flat fee of $58, to keep the website going. He looked at records, X-rays, listened to owners’ stories, and offered his professional opinion. He was never accused of harming or misdiagnosing animals.

Rowes said Hines wasn't treating or prescribing medicine for animals, including the cat in Nigeria, whose owner reportedly lived in a remote area with limited vet services. Rather, this was “about two grown-ups talking about dogs and cats, and if that doesn’t demand First Amendment protection, what does?”

Texas shut down Hines’ conversations in 2013, saying they violated the board’s 2005 rule about examining animals in person. Rowes said the Institute for Justice will be filing a brief asking the Supreme Court to intervene. “The rule is completely inflexible,” he told FoxNews.com.

The debate concerns human health care, too. Each state has different laws for how and when doctors can remotely treat patients. They are all uniform on the requirement that practitioners must be licensed, and many say doctors cannot prescribe drugs without at least one face-to-face consultation. From there, standards vary, particularly for the growing practice of doctors who have never met the patient in person but are “on call” for hotlines and clearinghouses, or through insurance companies.

Teledoc -- a telemedicine provider with 1,100 licensed practitioners who provide non-emergency consults to children and adults via Skype, email, phone, or mobile app -- recently ran up against a new proposed rule in Texas which would require an initial face-to-face consult before providers can prescribe medicine. In a statement to FoxNews.com, the Texas Medical Board explained that a “scenario that allows a physician to prescribe remotely, that does not verify who the patient is, relies solely on question and answer provided by the patient without any objective diagnostic data, and with no ability to follow up with the patient, does not meet the standard of care."

But Teledoc says their patients are typically hooked up through insurance providers, which have pre-arrangements with on-call doctors. Those doctors have access to patient files, and are required to look at them before they talk. The company challenged the Texas rule in court, charging that the state was stifling professional competition. A court granted Teledoc an injunction on the new rule on May 29 while the lawsuit plays out.

“In the face of increasing physician shortages and rising health care costs, other states across the country have found solutions that embrace telehealth, and all its benefits, while ensuring patient safety. Today’s court ruling allows Texans to continue enjoying these benefits as well,” said Jason Gorevic, Teledoc's CEO, in a statement.

The debate is not so black and white, even among the telemedicine community, said Jonathan Linkous of the American Telemedicine Association, which has not taken a position on the Teledoc case. "There are gray areas."

Linkous said his association, though, has criticized medical boards for sometimes "arbitrarily" setting the bar higher for their field, at times "because they want to hold back competition” against brick-and-mortar operations.

Wilson, despite his reservations, acknowledged further technological advancements could lead to a change in the laws someday. “Right now, the question has yet to be resolved,” he said.