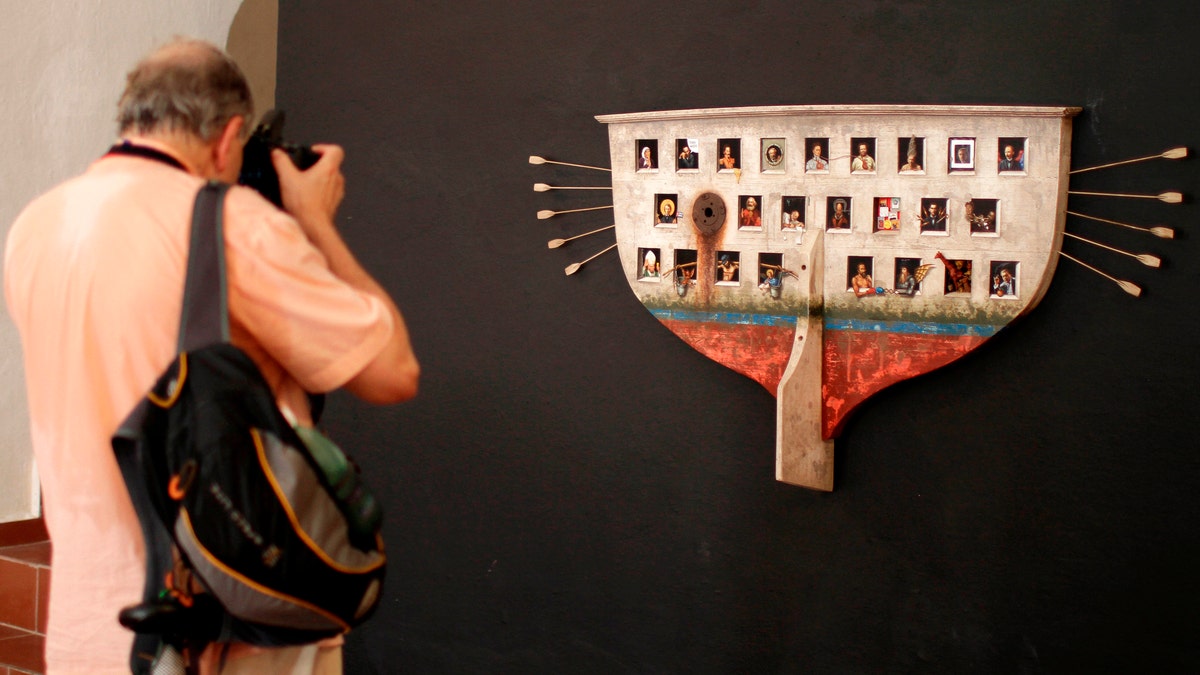

A visitor takes a picture of "My Ark" by Cuban artist Ruben Alpizar at the San Carlos de La Cabana fortress as part of the 11th Havana Biennial exhibition in Havana, Cuba, Friday, May 25, 2012. (AP Photo/Franklin Reyes)

For Cuban artists, U.S. collectors are providing a new source of much-appreciated cash.

Ruben Alpizar never met the American collector who fell in love with his painting of a plummeting Icarus against a starry background, hanging on the wall of a Spanish colonial-era fortress across the bay from Havana. Nor did he get a name or a hometown, or even learn whether the buyer was a man or a woman.

It all happened quickly, starting with a phone call from a broker. "How much for the painting? Look, I think somebody wants it. I'll call you right back." Soon after, the phone rang again: "Sold."

"We need more people coming from Gringoland," Alpizar said with a smile, not a hint of derision in his voice as he employed a term that can be either affectionate or pejorative depending on the context. "They pay the price you ask."

The streets of the Cuban capital are, in fact, awash with American art pilgrims during the monthlong Biennial, a showcase connecting local contemporary artists with well-heeled foreign collectors - key clients in a country whose citizens have little real purchasing power.

Alpizar, for one, would not say how much his painting sold for, but offered that his work normally goes for between $3,000 and $15,000, a windfall in a country where most people earn the equivalent of $20 a month.

The Americans are arriving in larger numbers because of the Obama administration's relaxation of U.S. embargo travel rules. They say they see a chance to explore the unknown and look for the ultimate conversation piece to hang on the living room wall.

"I think there is a mystique and the association with the 'time-capsule island' and all that's inaccessible," said Rachel Weingeist, an adviser to Shelley and Donald Rubin on their Cuban art collection. The couple's New York-based Rubin Foundation promotes the arts and humanitarian causes.

"Frankly we haven't had much access until recently," Weingeist said.

The Americans say they're impressed by the island's sophisticated fine arts scene compared to those in other countries in the Caribbean and elsewhere. Auctions by Christie's and Sotheby's have firmly cemented Cuban art in the U.S. consciousness, such as this week's sale of a painting by the late surrealist Wilfredo Lam for $4.56 million.

"There's so much heart. It's very intense. It's about a sense of place," said Jennifer Jacobs of Portland, Oregon, who led a private group of 15 collectors from Seattle to the Biennial. "It really spoke to me personally."

Terry Hall, an art collector and accountant from Gurnee, Illinois, just south of the Wisconsin border, said she was surprised by the variety she saw.

Cuban art embraces diverse themes and styles, and even ventures into the political. One piece on display at the Biennial, shaped like a mailbox, has a slot with large, sharp bloody fangs and an invitation for "Complaints and Suggestions."

"I came down here expecting art that was more colorful, more Caribbean in flavor and what I found is more international, more cutting-edge, more ambitious art," said Hall. "I've really been very excited about it. I think it rivals anything I've seen anywhere else as far as the execution, the expertise and the ambitious ideas."

More than 1,300 American artists, curators, collectors and fans have been accredited for the Biennial, organizers say, an unusually large delegation from what some say is the most important market for Cuban art. Unlike with other island goods, it's perfectly legal for Americans to buy Cuban art, which is covered under an exemption to the 50-year-old U.S. embargo allowing the purchase of "informational materials."

"They're coming by the busload," said Alpizar, who just two weeks into the Biennial had sold a half-dozen works including the piece featuring Icarus, entitled "Home." Another painting that was snapped up by an American collector, "My Ark," was a whimsical cross between a stern of a boat and a religious tableau, with famous historical figures peeking out from the windows: Ernest Hemingway, Karl Marx, Diego Rivera, Frida Kahlo and Pope John Paul II.

While Cuban emigrant artists living in Miami sometimes struggle to be noticed, artists who remain on the island enjoy the cachet of providing a kind of forbidden fruit for U.S. collectors. People on both sides of the exchange say the mutual affinity exists not despite but because of the five decades of geographical proximity and political animosity.

Many collectors are Cuban-Americans, perhaps eager to acquire a link to their lost homeland. Others are patrons from big cities such as New York, San Francisco and Seattle that are more open to detente.

"There's a very easy connection between us. The American public ... has a very special sensitivity to Cuban art," said Carlos Rene Aguilera, who exhibited a dozen paintings inspired by black holes, string theory and other scientific mysteries, hauled all the way from the eastern city of Santiago. "Maybe it's because of curiosity about each other's history. Maybe it's because we are neighbors and there is a messy relationship between our countries, so this creates interest."

So great is that interest that Americans are often willing to shell out the asking price with little background research, and with a little luck, even junior artists can command eye-popping prices. Tales abound about fourth-year university students selling pieces for $15,000, equal to the prices commanded by Alpizar, an established artist whose work has been shown in dozens of individual and collective exhibitions over a 23-year career.

"It's what the market will bear, and why not shoot for the moon?" Weingeist said. "All it takes is somebody feeling giddy who's got the money for something they like."

The transactions are usually handshake agreements to wire money to bank accounts holding international currencies that many artists prefer to keep in Spain, the Netherlands or Canada, rather than the local bank accounts for Cuban pesos used only on the island. The seller then ships carefully wrapped paintings to overseas addresses.

Galleries are cut out of their traditional middleman role, giving collectors the sense that they're getting a better deal. The arrangement also brings buyers in direct contact with the artists as they go knocking on the doors of home studios.

Artists say the Biennial is a crucial time to build their names and establish those contacts.

"I've collected a ton of business cards," said artist Tamara Campo, whose ode to the world financial crisis is installed in a bunker of La Cabana fortress. It features a wave of some 650 banknotes fashioned from fragrant cedar cascading from the ceiling into a jumbled pile on the floor.

"A lot of people want to talk to me," Campo said. "I have to check my email, because it's been days."

Based on reporting by the Associated Press.

Follow us on twitter.com/foxnewslatino

Like us at facebook.com/foxnewslatino