Hospitals and blood banks are adopting new measures to improve the safety of donated platelets—the tiny cells that make blood clot and heal injuries but that also present the No. 1 infection risk in the U.S. blood supply, the Wall Street Journal reported.

The biggest risk in the nation's blood supply is no longer HIV or hepatitis C, it's bacterial contamination of platelets, resulting in at least 20 deaths and hundreds of adverse reactions in recent years, health experts say. Laura Landro has details on Lunch Break. Photo: Photo Researchers Inc.

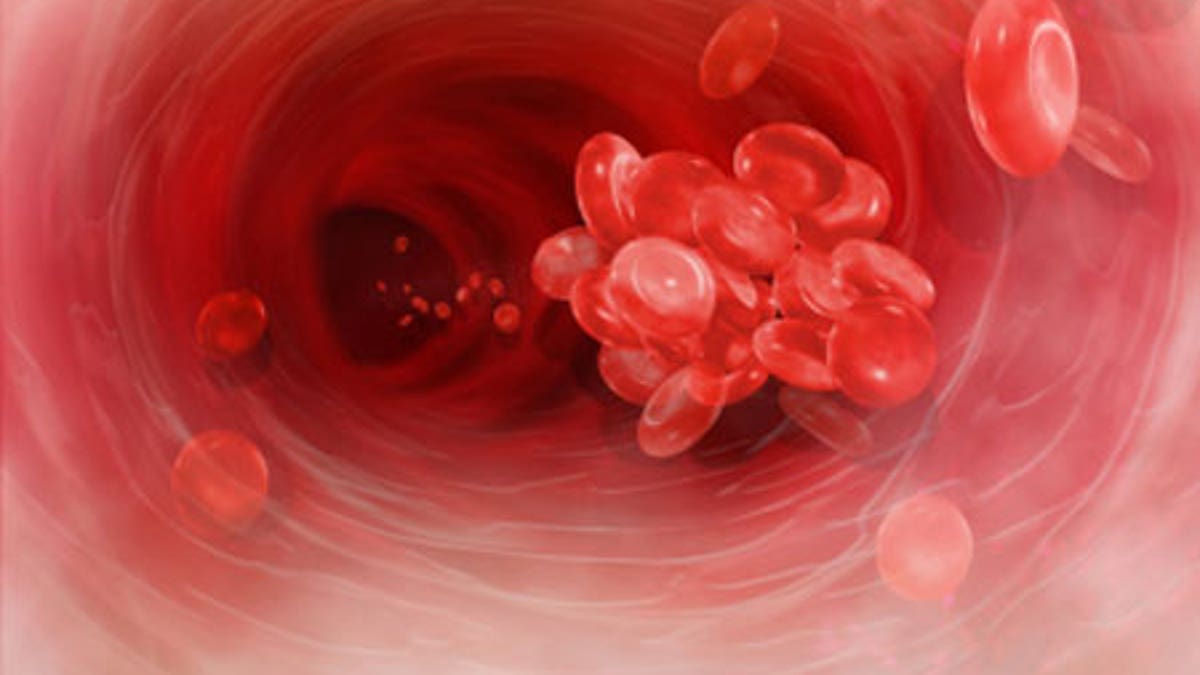

A growing number of studies show that standard tests performed by blood banks before they ship platelets to hospitals miss the majority of contaminated platelets. Unlike other blood components such as red cells, which are refrigerated, platelets must be stored at room temperature to remain effective, but during storage periods that last up to five days bacteria can grow and multiply.

About 150 hospitals have adopted a new contamination test, made by Verax Biomedical Inc., that can be administered immediately before patients get a transfusion. Initially approved by the Food and Drug Administration in 2007, one barrier is cost: It adds about $25 to $30 to the average $540 cost of a unit of platelets.

The infection risk from platelets beats that of HIV and hepatitis C, researchers say, since advances in testing and screening have all but eliminated the risk of contracting those viral infections through donated blood. The federal government is stepping up scrutiny: A congressional committee has asked the FDA to determine what further actions should be taken to reduce the risks and spread awareness among hospitals.

More than two million doses of donated platelets are transfused annually in the U.S. to prevent uncontrolled bleeding in trauma, cancer and surgical patients. Most are safe and well-tolerated. New safety standards adopted by blood banks in 2004 have reduced the average rate of fatalities from sepsis, or blood poisoning, to three a year from between seven to 11 annually. Still, hundreds of nonfatal sepsis cases and other adverse reactions are still linked to contaminated platelets. Experts say the rate may be much higher than reported because infections might have been attributed to other causes.