If you're getting a drug injection for macular degeneration or another eye condition, a new study suggests you might want to make sure your doctor doesn't talk while doing the procedure.

Researchers found that in just a few minutes of talking over an imaginary patient, unmasked volunteers spewed out bacteria which could potentially land on eyes or injection needles and cause infection.

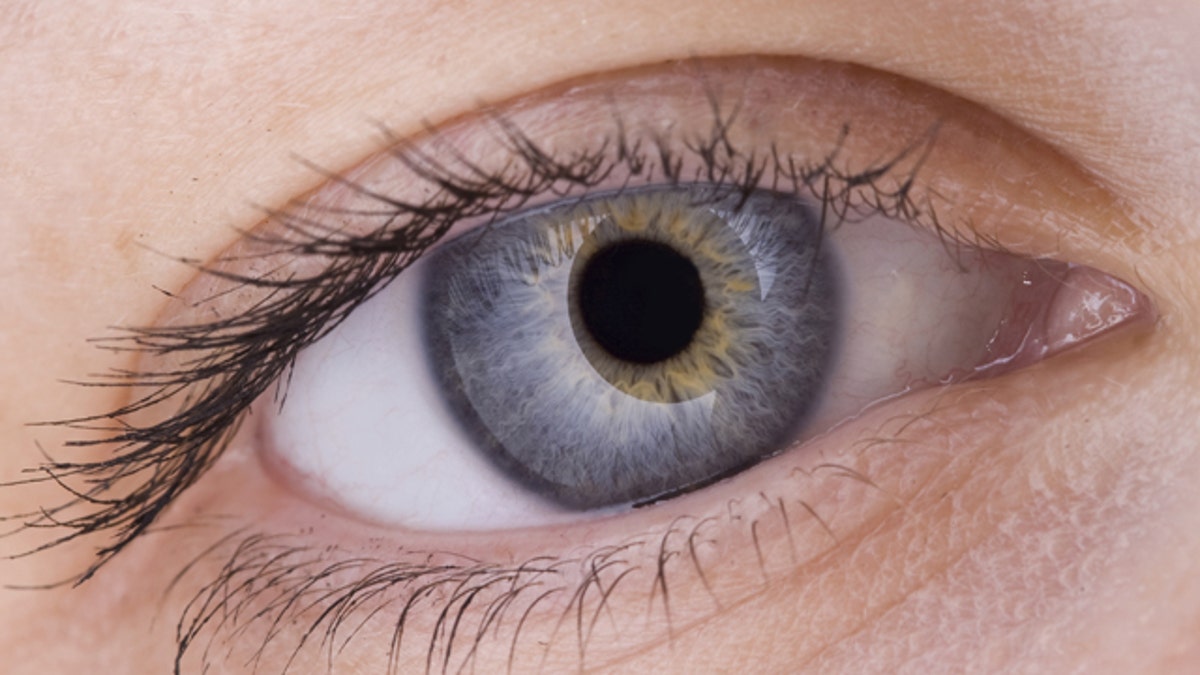

One in every few thousand injections for vision loss results in a serious eye infection called endophthalmitis, which at its worst can cause patients to go blind completely. But because patients typically need frequent injections, as many as 1 in 200 eventually get the infection.

Some of those infections are caused by a type of bacterium, Streptococcus, that's common in the mouth and also leads to bad breath and cavities.

The new finding "doesn't prove anything conclusively," said study author Dr. Colin McCannel, from the Jules Stein Eye Institute at the University of California, Los Angeles.

Still, he said, "My advice to patients would be, until the injection is complete ... minimize conversation or talking with the physician."

McCannel and his colleagues simulated a typical eye injection appointment in an ophthalmologist's office. Volunteers stood in front of an exam chair, which had a plate for culturing bacteria placed where a patient's head would be.

There, they read from a script for five minutes under different conditions -- facing directly at the imaginary patient, with or without a mask, or facing sideways mask-free. Then, they stood in silence for five minutes. In a role reversal, the volunteers also took a go lying in the exam chair, reading the script with a bacteria plate mounted to their own foreheads.

When the 15 volunteers talked while wearing a mask or stood in silence, hardly any bacteria grew on the plates. But when they didn't wear a face mask, either while facing the patient or turned away, most plates sprouted bacteria colonies. And when "patients" talked themselves, about half of the plates grew bacteria.

That shows that even though the eye injections aren't major procedures and don't happen in an operating room, patients and their doctors should still take the possibility of eye or injection needle contamination seriously, researchers said.

"This is really a surgical procedure," said Dr. Charles Wykoff, an ophthalmologist from Retina Consultants of Houston who wasn't involved in the new study.

"You're putting a hole in someone's eye. It's a teeny tiny hole, but nonetheless, that's probably where an infection's coming from," he told Reuters Health.

Germs from a chatty doctor or assistant could be a concern in some other instances as well, the researchers wrote in Archives of Ophthalmology. McCannel pointed to a few cases where bacteria in a doctor's mouth were linked to meningitis cases in patients who had recently gotten spinal taps.

Both Wykoff and McCannel didn't go so far as to say that doctors should always wear face masks during the eye injections -- but they did say that if possible, both doctors and patients should try to keep talking to a minimum.

At the very least, "physicians should minimize conversation," McCannel told Reuters Health. "I've started using a face mask, because that way I can talk to the patient and have less concern of contamination."