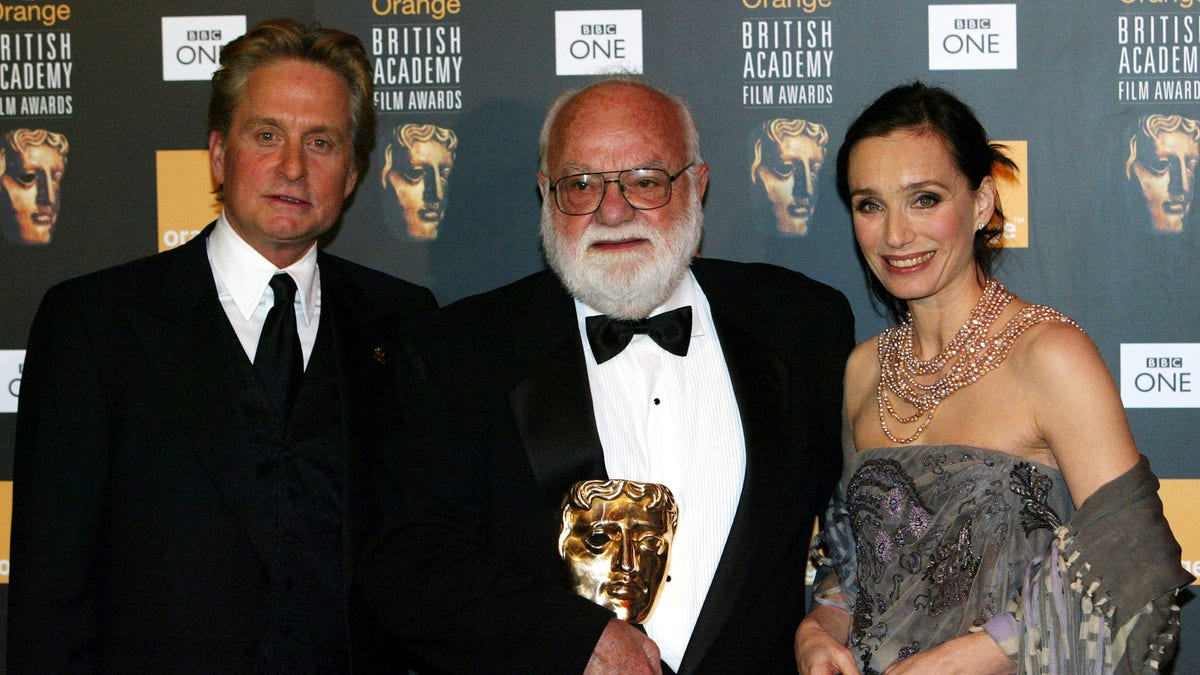

February 23, 2003. Michael Douglas presents producer Saul Zaentz with The Academy Fellowship as he stands flanked by British actress Kristen Scott-Thomas during the British Academy of Film and Television Arts (BAFTA) Awards at the Odeon Leicester Square in London. (Reuters)

Producer Saul Zaentz, who won best picture Oscars for “One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest,” “Amadeus” and “The English Patient,” died Friday in the San Francisco Bay Area. He was 92 and had been suffering from Alzheimer’s.

The entrepreneurial and famously litigious Zaentz, who spent most of his life as a record producer, did not become involved in the movie business until he was in his 50s. He produced only a handful of movies — many of them self-financed.

But his foresight in acquiring rights to prestigious novels including J.R.R. Tolkien’s “The Lord of the Rings” trilogy and “The Hobbit” led to blockbuster payoffs. In many cases, the profits led to lawsuits. His courtly, grandfatherly manner belied his ferocious attempts to hold on to rights and returns he felt he was entitled to.

His productions usually came with literary pedigrees — 1975’s “Cuckoo’s Nest” was based on Ken Kesey’s iconoclastic novel; 1984’s “Amadeus” was adapted from Peter Shaffer’s stage drama; and 1995’s “The English Patient” was based on the Michael Ondaatje novel.

In between were such noble efforts as “Payday,” “The Unbearable Lightness of Being,” “The Mosquito Coast” (which he exec produced), “At Play in the Fields of the Lord” and the 1978 Ralph Bakshi-animated “Lord of the Rings.” Most of his movies were financially successful, though the failure of “At Play” led him to seek outside financing sources for “The English Patient,” which was a worldwide box office success.

The same year that he walked off with his third producing Oscar, for “The English Patient,” bringing him into the rarefied company of other triple winners Darryl F. Zanuck and Sam Spiegel, he was awarded the Irving Thalberg Award for his efforts as a producer. He was the first producer since Cecil B. DeMille (1952) to win the Oscar and be awarded the Thalberg in the same year.

Born in Passaic, N.J., he ran away from home at age 16 and made a living selling peanuts at the St. Louis Cardinals training camp and as a gambler. His first love was jazz, and after he served in the Army in WWII in North Africa and Sicily, he went to work with San Francisco-based jazz producer and promoter Norman Granz.

It afforded him the opportunity to travel with one of his teenage idols, Duke Ellington, as well as to be in the company of such greats as Dave Brubeck and Gerry Mulligan. By the mid-’50s he was working for the select Fantasy Records, a jazz and comedy label, and was instrumental in waxing Brubeck, Lenny Bruce and Mort Sahl.

Fantasy appeared destined to be a cult label until its hit recording of Vince Guaraldi’s “Cast Your Fate to the Wind.” Several years later, backed by investors, Zaentz bought Fantasy and signed a promising country rock group called the Golliwogs. Soon thereafter they changed their names to Creedence Clearwater Revival and, with lead singer and songwriter John Fogerty, became a sensation with such songs as “Proud Mary” and “Down on the Corner.” CCR sold more than 5 million records, and in his first of several major legal battles over his lifetime, Zaentz would be involved in (and emerge victorious) in a battle with Fogerty over the rights to the Creedence catalog. Forgerty, then solo, would write such ditties as “Mr. Greed” and “Zanz Kant Danz” in retaliation.

A second suit followed in 1985, when Zaentz accused Fogerty of stealing his own song “Run Through the Jungle” for his new tune “Old Man Down the Road.” Zaentz lost that one. Fantasy was sold to a consortium led by Norman Lear and merged with Concord Records in 2004.

Zaentz became involved in movies when he optioned two novels, Ken Kesey’s “One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest” and Peter Matthiessen’s “At Play in the Fields of the Lord,” in 1968. In the meantime, he filmed an original piece, “Payday,” starring Rip Torn as a country singer. It was one of Zaentz’s favorite films, even though it lost money (and cost less than $1 million to produce).

“Cuckoo’s Nest,” which he co-produced with Michael Douglas, finally came together in 1975 and was largely self-financed. It won several Oscars, including best picture, director (Milos Forman) and actor and actress (Jack Nicholson, Louise Fletcher). It also made a good deal of money (Kesey tried to sue for not receiving his fair share).

In between Oscars Zentz also produced “Three Warriors” (1977) and an animated version of “Lord of the Rings” (in 1978). He contended that most of his movies at least broke even, enough for him to repay the loans on his Fantasy Records building in Berkeley.

And the ones that were profitable did extremely well for him, allowing him to finance his other projects. In 1984, working again with director Forman, he adapted Shaffer’s stage play about Mozart, “Amadeus,” to the screen.

Again, he walked away with an armful of Oscars including picture, director and actor.

His adaptation of Milan Kundera’s “The Unbearable Lightness of Being,” directed by Philip Kaufman, was more than respectfully received, introducing American audiences to such future Oscar winners as Daniel Day Lewis and Juliette Binoche. Kaufman sued for a higher salary, and Zaentz paid him $150,000 as part of a Directors Guild settlement.

Raising the money for “The English Patient” was a herculean task as 20th Century Fox pulled out of the movie at the last minute over casting problems (they wanted a big star like Demi Moore to play the Kristin Scott Thomas role). Zaentz went to Miramax for the $27 million he needed to complete the film (it cost about $35 million); Miramax turned to its parent, Disney. The success was his biggest to date, winning a near record nine Oscars.

He worked with Forman once again on “Goya’s Ghost,” which went largely unnoticed.

In 1997 he allowed Miramax to option the “Lord of the Rings” property, to which he had obtained the rights in 1976, after it became a counterculture hit. Miramax could not financially commit to making more than one film, so director Peter Jackson took the project to New Line. The “Lord of the Rings” trilogy grossed more than $2.9 billion theatrically worldwide and became one of the most successful film franchises of all time, but Zaentz twice sued New Line over profit accounting, eventually settling with the studio. He also served as producer for legit theater versions of “Lord of the Rings.”

He is survived by a four children, Dorian, Joshua, Athena, and Jonnie; seven grandchildren, and his nephew, Paul Zaentz, a producer.