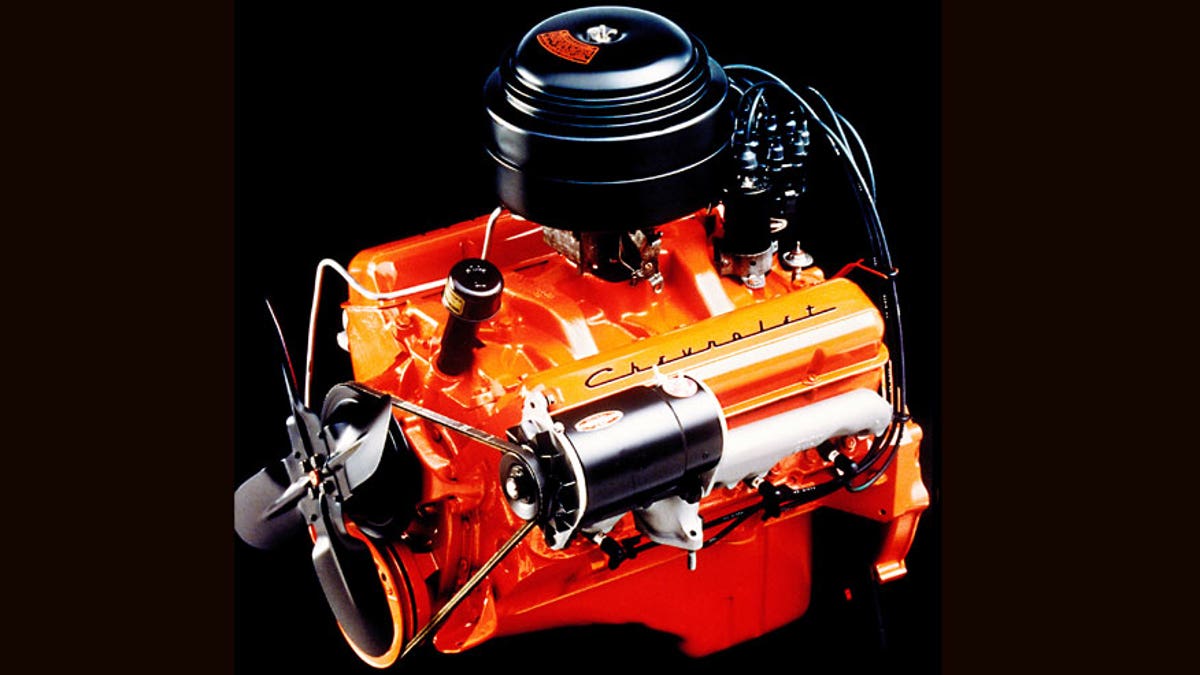

(Chevrolet)

It’s an engine that has touched so many lives that, no matter where your car brand loyalty lies, chances are good that you’ve got a personal story about one. It has powered tens of millions of passenger cars, trucks, race machines and boats. Calling it an American icon would not be an overstatement or hype.

“It” is the Chevy small-block V-8, and General Motors is celebrating this influential engine’s 60th anniversary.

Introduced as a durable yet inexpensive-to-build upgrade engine in the 1955 Chevrolet line, the second V-8 in the brand’s history (the first was in 1917) was as warmly embraced by average car buyers as by hotrodders. The engine, which Chevy called the Turbo Fire, wasn’t nicknamed the “small-block” until the Mk. IV “big-block” arrived in 1965.

While GM’s Gen IV and Gen V V-8s power new Corvettes, Camaros, pickups and SUVs, the original small-block continues in production for marine use and as a series of crate engines for hotrodders, racers and builders.

Looking back six decades, the circumstances that made the small-block a legend can seem almost coincidental. Chevy was already developing a small-displacement V-8 when Ed Cole, who’d headed development of the Cadillac V-8, was put in charge of Chevy engineering in 1952. He immediately scrapped the V-8 project to develop something truly innovative and in tune with Chevy’s character.

In New York, meanwhile, seeing the Motorama Corvette show car inspired the Belgian-born Russian engineer Zora-Arkus Duntov to seek employment with Chevrolet. Duntov had developed an overhead-valve conversion for the Ford flathead and had driven a Cadillac-powered Allard at Le Mans, so he knew a thing or two about American V-8s. At Chevrolet, he saw in the new V-8 great potential to attract the youth market.

Taking a bold step, Duntov sent his boss, Maurice Olley, a memo he titled, "Thoughts Pertaining to Youth, Hot Rodders and Chevrolet.” Duntov made the case for offering a line of factory performance parts for the Chevy V-8 as a way to attract a new generation of customers to the brand. One passage from the memo, in particular, captured Duntov’s intuition for engineering and marketing:

“The association of Chevrolet with hot rods, speeds and such is probably inadmissible, but possibly the existence of the Corvette provides the loop hole. If the special parts are carried as RPO [regular production option] items for the Corvette, they undoubtedly will be recognized by the hot rodders as the very parts they were looking for to hop up the Chevy.”

Cole eventually got on board, and Duntov would go on to lead Corvette engineering. His ideas for the small-block would upend American performance and hotrodding. With the small-block, Duntov saved the floundering Corvette from an early demise, and the Corvette program in turn helped ensure continual performance development for the small-block.

The features that made the new Chevy engine lighter and less costly to build versus other V-8s also endowed it with good breathing, reliability and durability. Its thin-wall block casting ended at the crankshaft centerline, unlike the deep-skirted blocks used on other V-8s. Mounting stamped-steel rockers to ball studs rather than using a traditional rocker shaft arrangement saved cost and lightened the valve train considerably, giving the small-block high-rev potential.

The 265 cu. in. Chevy V-8 debuted with 162 hp using a 2-barrel carburetor and 180 hp with an optional Power Pack – a 4-barrel carb and dual exhausts. The 1955 Corvette got its own version with a “Duntov cam” for 195 hp.

Displacement grew to 283 cubes in 1957, when mechanical fuel injection was offered for both the Corvette and regular Chevys. Ads touted America’s first engine with one horsepower per cubic inch. In addition to Chevy’s own performance parts, the aftermarket exploded with choices for hotrodders. A bigger bore and longer stroke yielded 327 cubic inches in 1962, and interchangeability within the small-block family bolstered performance potential.

A string of legendary small-blocks originated with the Corvette and later, the Camaro, a tradition that continues to this day. Among the 1960s Corvette gems were the 375-hp L-84 fuel-injected 327 and its hydraulic-cam, 4-barrel carb sibling, the L-79. This 350-horse version was also available in the Chevelle, and for 1966 the option turned the Chevy II Nova into a budget muscle car.

When Chevy fielded the Camaro Z/28 to compete in the Trans-Am racing series, it borrowed a trick from oval-track racers who’d been putting a 283 crankshaft in a 327 block to get a high-revving 302. Chevy stuffed the production version with its best high-performance parts.

The 350 cu.-in. small-block debuted in the 1967 Camaro and then proliferated throughout the Chevy line. At the dawn of the low-compression, low-emissions era, Chevy kept performance alive with the 250-hp (net) L-82 in the Corvette and Z/28.

You didn't need one of the high-performance versions to have fun, though. Almost any small-block had some hop-up potential. And, performance wasn’t the engine’s only calling card. Millions of drivers enjoyed its reliability and durability in everyday cars and trucks. The small-block eventually became GM’s mainstay V-8, powering vehicles from all of the corporation’s brands, except Saturn.

In the mid-1980s, electronically controlled Tuned Port Injection brought performance back to the Corvette and Camaro. And in 1990, the Corvette ZR1 introduced a radical DOHC aluminum small-block, engineered with help from Lotus in England.

The Gen II brought another big performance jump for 1993, thanks to such improvements as reverse cooling, which allowed higher compression ratios. With up to 330 net hp in the 1996 Corvette, the Gen II was more powerful than most of its Gen I ancestors.

In 1997, the truly new Gen III small-block debuted as the aluminum LS1 in the ’Vette, and then in the Camaro Z28 and Pontiac Firebird models the following year. This modern engine kept key elements of the original, including 4.4-inch bore centers (the center-to-center distance between cylinders) and two valves per cylinder actuated by pushrods operated by a single camshaft.

Indeed, the newest Gen V engine in the Corvette Stingray still shares those attributes. Features like variable valve timing and cylinder deactivation have helped the modern small-blocks deliver higher fuel economy.

GM doesn't label its sole family of gasoline V-8s “Chevy” these days, and the continuity from the original small-block is more of a marketing strategy than an engineering reality. But that’s also true of other engines that are intrinsically linked with their brand’s heritage, including the Chrysler HEMI, Ferrari V-12 and Porsche flat-six.

After 60 years, that’s mighty good company to be in.

Click here for more from Hagerty or here sign up for their classic car newsletter