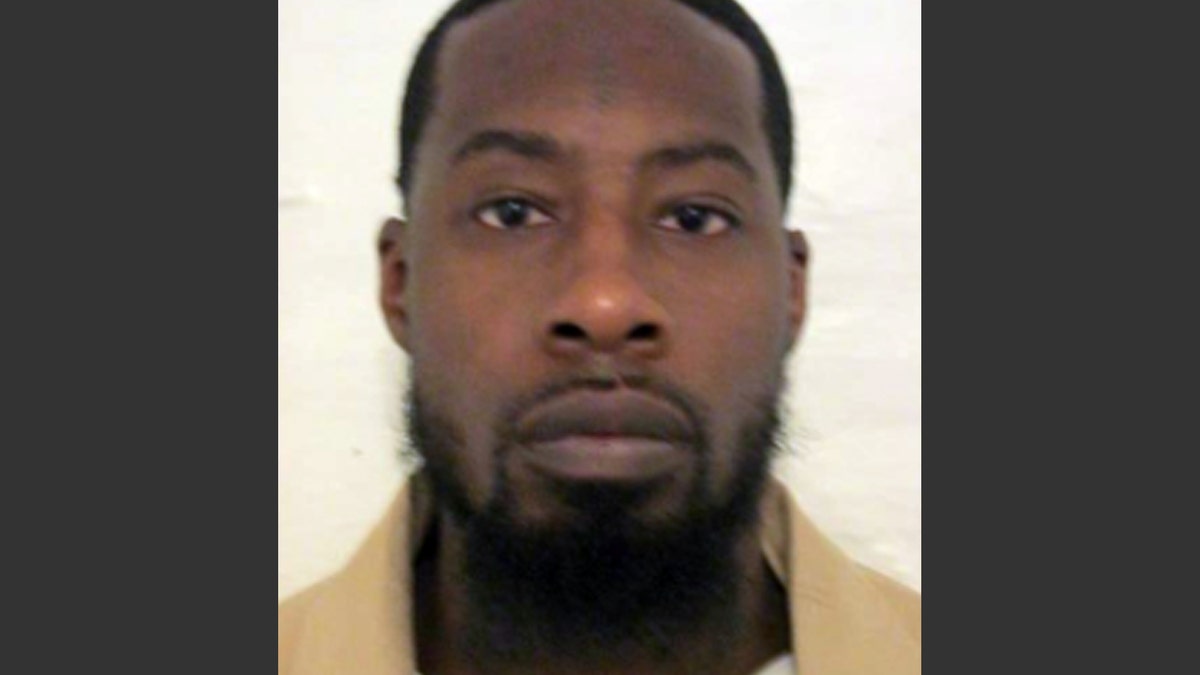

This undated photo provided by the New Jersey Department of Corrections shows Vonte Skinner. Skinner, whose rap lyrics boasted he would "blow your face off and leave your brain caved in the street" will have his attempted murder case considered by New Jersey's Supreme Court, which will decide whether the words he penned should have been admitted at trial. Skinner's case is being watched closely by civil liberties advocates who contend the lyrics should be considered protected free speech under the Constitution. (AP Photo/New Jersey Department of Corrections)

NEWARK, NJ – A New Jersey man whose rap lyrics boasted he would "blow your face off and leave your brain caved in the street" will have his attempted murder case considered by the state's Supreme Court, which will decide whether the words he penned should have been admitted at trial.

Vonte Skinner's case is being watched closely by civil liberties advocates who contend the lyrics should be considered protected free speech under the Constitution. In an amicus brief in support of Skinner, the ACLU New Jersey contends that rap lyrics, because of their violent imagery, are treated differently than other written works.

"That a rap artist wrote lyrics seemingly embracing the world of violence is no more reason to ascribe to him a motive and intent to commit violent acts than to ... indict Johnny Cash for having `shot a man in Reno just to watch him die,"' according to the brief.

After an initial trial ended without a verdict, Skinner was convicted at a second trial of shooting Lamont Peterson multiple times at close range in 2005, leaving Peterson paralyzed from the waist down. Peterson was reluctant initially to identify Skinner as the shooter, but eventually testified at the trial that Skinner was the assailant. Peterson testified the two men sold drugs as part of a three-man "team" and developed a dispute when Peterson began skimming some of the profits for himself.

During the trial, state prosecutors read 13 pages of rap lyrics that were found in the back seat of the car Skinner was driving when arrested. The writings, some penned three or four years before the Peterson shooting, include a reference to "four slugs drillin' your cheek to blow your face off and leave your brain caved in the street."

Another passage describes a mother in a mortuary, taking clothes "red soaked ravaged with holes" and "Wonderin' if you died in pain. Was it instant or did you feel the slugs fryin' your veins."

In a 2-1 ruling that overturned the verdict, an appellate court noted that, similar to admitting evidence of prior crimes, caution must be exercised when allowing prior writings as evidence in a trial. The judges also wrote that the lyrics weren't necessary to buttress the state's case.

"This was not a case in which circumstantial evidence of defendant's writings were critical to show his motive," the majority wrote. "Nor was such evidence important to show that defendant had the intent to kill Peterson, which the State was required to establish to prove attempted murder. This brutal shooting bespoke intent to kill."

Judge Carmen Alvarez wrote in a dissenting opinion that the lyrics' relevance in showing motive and intent outweighed their prejudicial effect on the jury, and that "defendant's songs narrated events similar to the conduct which resulted in the charged offenses."

In its brief, the ACLU said that an analysis of similar cases in other states found that in 14 of 18 instances, judges allowed rap lyrics to be admitted as evidence. The brief urges the Supreme Court to toughen the standards for admitting lyrics as evidence in a trial.

"We're not saying song lyrics can never be evidence, but that there needs to be a direct connection to the crimes," said Jeanne LoCicero, deputy legal director of the ACLU New Jersey.

The Burlington County prosecutor's office, which is to argue the case before the Supreme Court, declined to comment on the case.