BATON ROUGE, La. – JAMIE OERTEL

Jamie Oertel grew up in Slidell in what she calls a "criminal environment."

Her mother was — and still is — a heroin addict, and by the time she was a teenager, Oertel was determined to go into law enforcement. As she got older, her sights narrowed on becoming a probation and parole officer.

"I wanted to play my part and help the people I could help," Oertel said. "Nobody comes here hoping to just put people in jail. Our job is to actually keep you out of jail."

She finds satisfaction in helping others turn their lives around, but admits it can be frustrating because she and her colleagues rarely get public acknowledgement for their hard work.

"People don't know what we do," Oertel said. "We're not just sitting in an office somewhere. We play so many different roles: We're counselors, social workers, and even teachers since some of my cases don't know how to budget money."

___

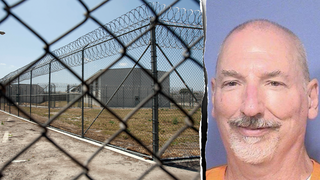

CASS MITCHELL

Cass Mitchell knows that if one of his cases reoffends, it will end up on the news.

That's because Mitchell monitors sex offenders.

Over the course of about three hours on a recent morning, Mitchell visited a dozen homes on a route that went from some of Baton Rouge's poorest neighborhoods to some of its wealthiest.

When he enrolled 11 years ago, Mitchell, 33, thought of the job as a steppingstone to another law enforcement department such as the national Drug Enforcement Administration. But now, he says, he can't imagine leaving.

"When you're a cop, you get a call and you go and help someone immediately — but you may never see that person again," Mitchell said. "When you do this job long enough, you actually see people's lives change."

___

FRAMMY FIGUEROA

During a graduation ceremony for 20 soon-to-be probation and parole officers, East Baton Rouge District Attorney Hillar Moore opted against soaring rhetoric, and instead stuck to the facts.

"Your (caseloads) are already very, very high, which makes it very difficult for you to do your job," Moore told the cadets inside a Baton Rouge auditorium. "You're not going to have an easy job."

That sense of foreboding didn't seem to fluster Frammy Figueroa, the class speaker.

Figueroa followed Moore's matter-of-fact speech with a more light-hearted look back at his classmates' accomplishments during their 14-week training program.

After the ceremony, Figueroa said he had heard a lot about recent legislative changes that could translate into much higher caseloads for parole officers in the future, but he wasn't too worried about his job becoming unmanageable. His bosses wouldn't set him up to fail, he reasons.