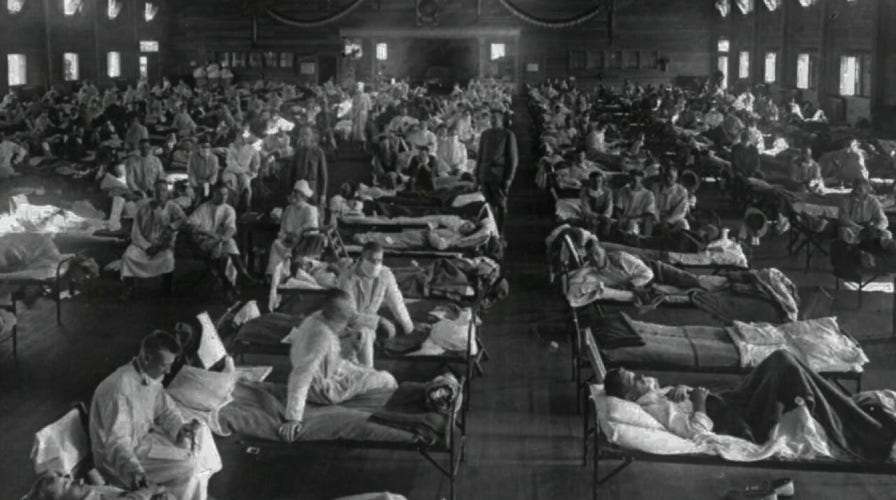

Lessons from the Spanish Flu: 50 to 100 million died worldwide during outbreak

The flu pandemic swept the globe in 1918 and changed the course of history; State Department correspondent Rich Edson reports.

Get all the latest news on coronavirus and more delivered daily to your inbox. Sign up here.

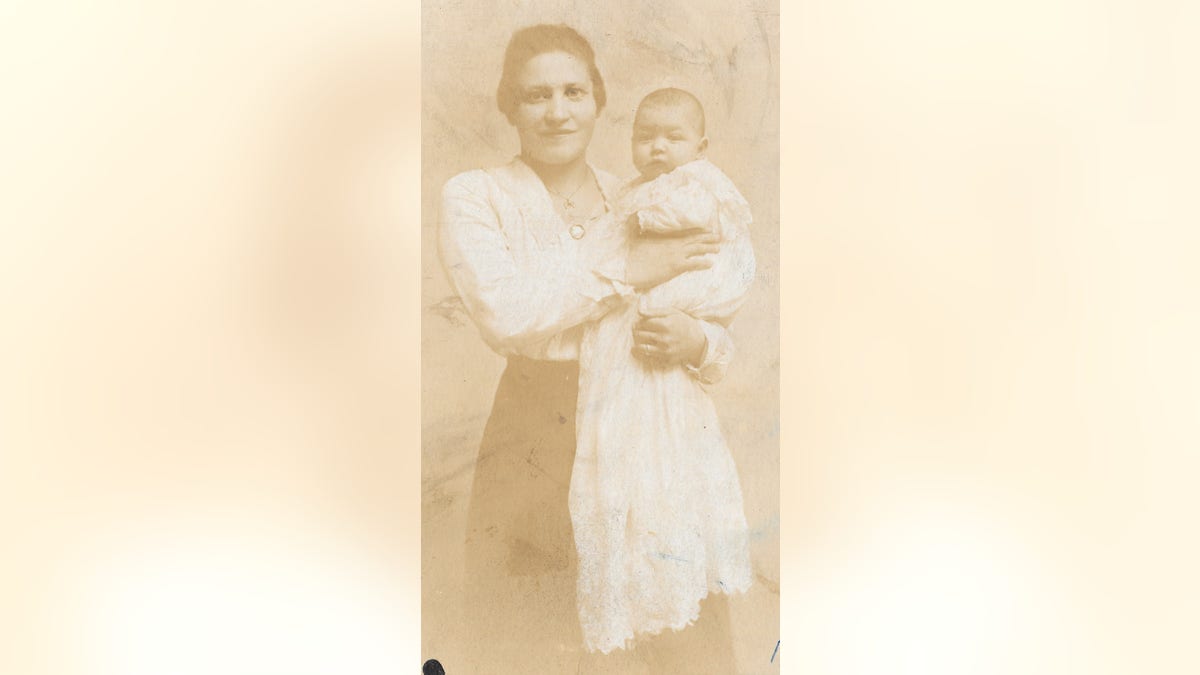

Angelina DiGiacomo brought her five-month-old daughter to New York City to celebrate Christmas of 1918 with her parents. Less than a week into the new year, 19-year-old Angelina was dead, one of the 50 to 100 million victims of a worldwide flu pandemic.

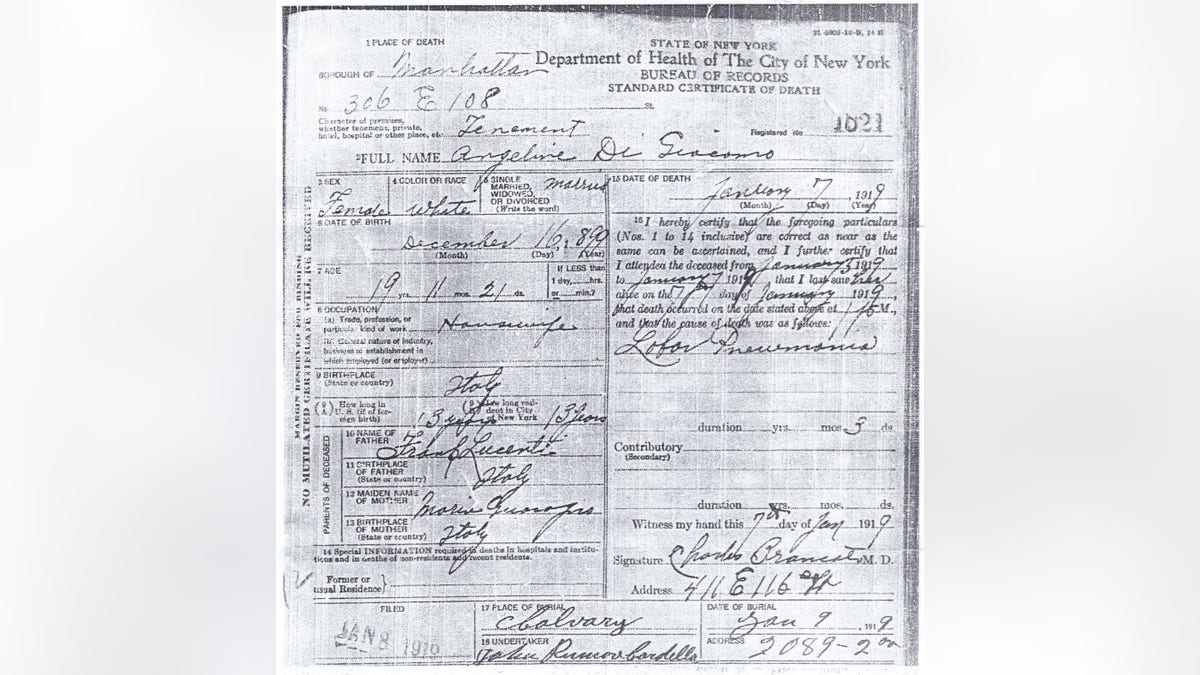

Angelina's death certificate cites “labor pneumonia” as the cause, a common citation for a flu pandemic especially lethal to young adults.

Angelina DiGiacomo and her daughter in 1918.

“One of the big differences between coronavirus and 1918 is that 1918 targeted otherwise healthy young adults,” says John Barry, the author of the 2004 book “The Great Influenza: The Story of the Deadliest Pandemic in History.” "Probably two-thirds of the deaths were people aged 18 to 45 or so.”

THE CORONAVIRUS OUTBREAK, STATE-BY-STATE

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) refers to the 1918 pandemic as the “deadliest flu.” While that virus is different from the current pandemic, the measures governments took to confront the 1918 flu resemble some efforts today. Many of the successes, and failures, from 1918 provide valuable lessons for 2020.

“Number one, give people the straight facts,” says Barry. “Number two, social distancing works, but only when it's imposed early. And it has to be sustained."

It’s unclear where the earlier flu started. In 1918, the United States was still mobilized for the First World War. Early in that year, reports of flu infections surfaced among American troops who were traveling throughout the country and across the Atlantic Ocean to fight on European battlefields.

Angelina DiGiacomo's death certificate, dated Jan. 7, 1919. The cause, "labor pneumonia," is noted on the right-hand side.

“When I was in the Officer’s barracks, four of the officers of whom I has charge died,” one volunteer nurse assigned to different military installations wrote to a friend at the Haskell Indian Nations University in Kansas. "The first one that died sure unnerved me – I had to go to the nurses’ quarters and cry it out. The other three were not so bad.”

A deadlier second wave struck that fall. Cities like New York staggered business hours, encouraged some social distancing and enforced anti-spitting laws.

"Most places did not impose these restrictions until it was too late, until the virus had already started killing large numbers of people in their community.” says Barry. "By then the virus was really all over the place.”

New York City officials posted public warnings, but kept theaters and schools open, figuring that they could help educate and monitor the public -- and presuming that those places were cleaner than the city's tenement apartments. Quarantine orders were difficult to enforce and likely ignored.

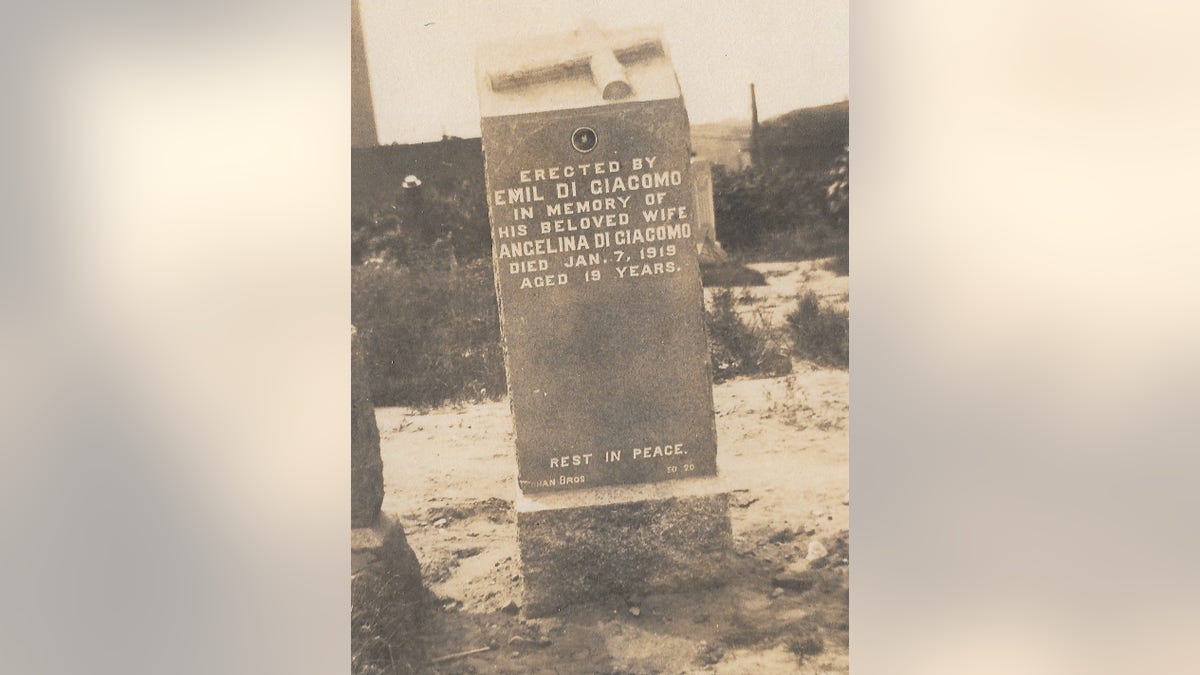

Angelina DiGiacomo's gravesite at Calvary Cemetery in Queens, 1920.

“It seems unlikely that individual doctors were able to ensure their patients complied with their orders to stay home during a time when doctors in New York City's [Lower] East Side neighborhood were reportedly ‘mobbed by women demanding their services,’ researcher Francesco Aimone wrote in a 2010 paper, "The 1918 Influenza Epidemic in New York City: A Review of the Public Health Response."

By the summer of 1919, the flu had dissipated as those infected either died or developed immunity.

Angelina DiGiacomo was buried in Calvary Cemetery in Queens, along with thousands of other flu victims. Her baby daughter stayed in New York, where Angelina’s parents raised her. That little girl, renamed Angelina after her mother, grew up to have three children and seven grandchildren.

Her youngest daughter is a nurse, still working in a New Jersey hospital inundated with coronavirus patients.

I’m her youngest grandson. Until her death in 2016, my grandmother would talk about the 1918 flu that took her mother, altered her life and changed the world more than a century ago.