A New Zealand woman who chose not to vaccinate one of her children was candid when describing how her decision ultimately put her son’s life in jeopardy.

Ally Edward-Lasenby told the radio station “The Hits” she chose to vaccinate one of her children but not her son Cameron, who later contracted the measles and became very ill.

When probed by the radio hosts as to why she made the choice not to vaccinate Cameron, Edward-Lasenby said a “research” paper that claimed there was a link between vaccinations and autism influenced her decision.

The paper Edward-Lasenby was seemingly referring to was published in the medical journal The Lancet in 1997, but was retracted in 2010 due to its incorrect elements and ethical violations, among other reasons. Separate studies conducted following the report’s initial release did not find a link between any vaccine and autism, ultimately debunking its claims.

“I made what I thought was an informed decision at the time,” she said.

Edward-Lasenby’s son Cameron later contracted the measles, an experience she said she “wouldn’t wish on anybody” and which she noted could have been prevented if her son had been vaccinated against measles with the MMR vaccine.

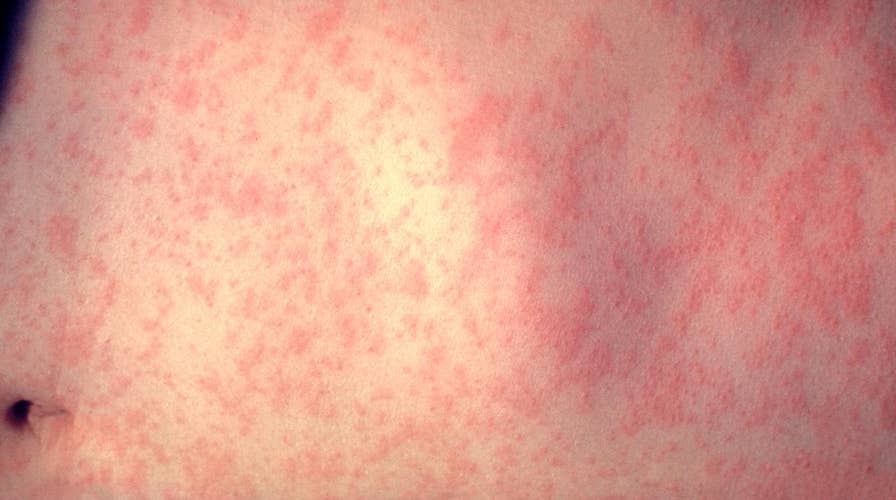

After initially being diagnosed with the flu, Cameron’s condition quickly worsened, Edward-Lasenby said. He suffered from a rash and conjunctivitis — common signs of measles.

"[The doctors] took one look at him and said, 'You can get him to the hospital first or we can get an ambulance here,'" she said.

Once they arrived, Cameron was confirmed to have measles.

"I believe that it’s important to immunize. We wouldn’t be in that position [if we had]. I played Russian roulette with my son’s health, which I’m not proud of.”

“Initially, he had white spots on his mouth," she said. "He had conjunctivitis. He was really unwell. He continued to deteriorate, and a rash came all over his body. Then they were talking about brain damage — potential brain damage — and the potential loss of life too because it was quite serious."

The measles is a highly contagious virus that spreads through the air after an infected person coughs or sneezes. Others can contract measles when they breathe the contaminated air or touch a contaminated surface, and then touch their eyes, nose or mouth.

“Infected people can spread measles to others from four days before through four days after the rash appears,” says the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, or CDC.

The MMR vaccine can protect both individuals and other people from contracting the virus.

Young children are typically most at risk of contracting measles. The CDC recommends children get two doses of the MMR vaccination, but the first dose is typically given to children when they are between 12 and 15 months old, with the second occurring between ages 4 and 6.

APPARENT ANTI-VAXXER WEARING 'JESUS WASN’T VACCINATED' SHIRT SLAMMED ON TWITTER

After he was treated for measles, Cameron developed pneumonia, his mother said. As a result, he suffered from a compromised immune system for months.

“He was in and out of school on a regular basis,” she said.

"I believe that it’s important to immunize. We wouldn’t be in that position [if we had]. I played Russian roulette with my son’s health, which I’m not proud of,” she added.