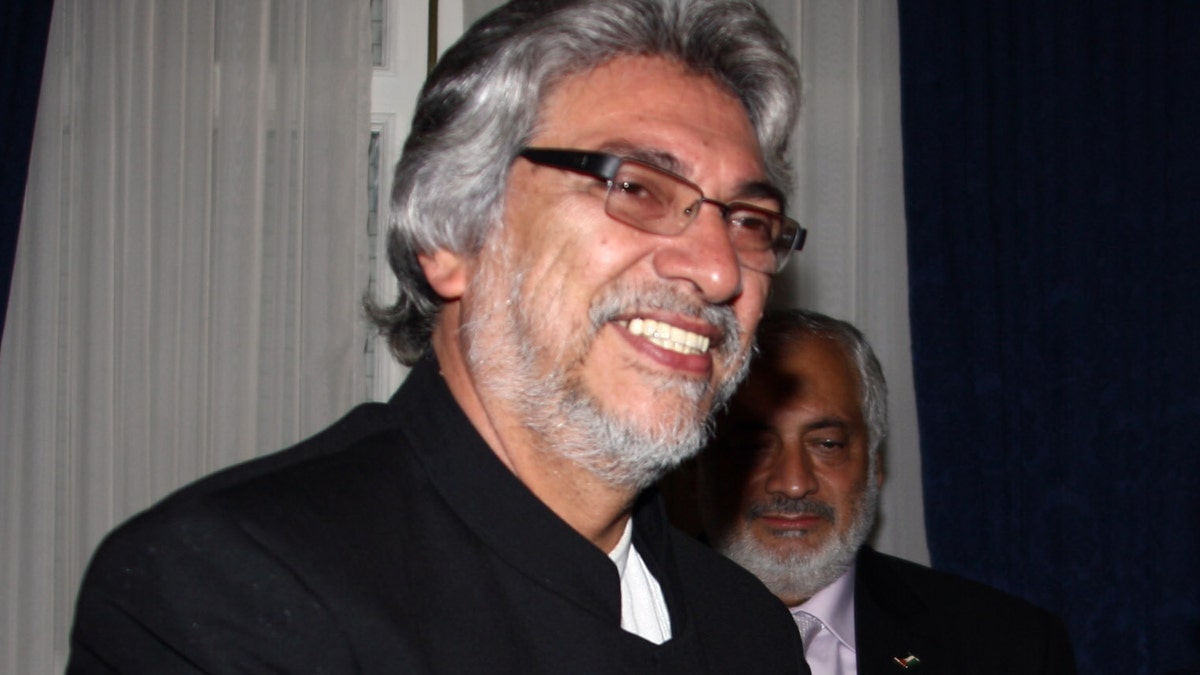

ASUNCION, PARAGUAY - NOVEMBER 26: In this handout image provided by the Palestinian Press Office (PPO), Palestinian President Mahmoud Abbas (R) meets with Paraguay's President Fernando Lugo at the Presidential Residence on November 26, 2009 in Asuncion, Paraguay. The leader was next bound for Venezuela to discuss with President Hugo Chavez opening an embassy and the stationing of an ambassador from Venezuela in Palestine. (Photo by Omar Rashidi/PPO via Getty Images) (2009 PPO)

Some may want to see last weekend’s sudden impeachment of Paraguayan President Fernando Lugo as a replay of the 2009 Honduran presidential crisis, but they are similar only in that each country’s legislature and judiciary, the other principal institutions of democratic governance, moved in unison to depose the chief executive, always taking pains to assert the constitutionality of the process.

The crucial distinction is what precipitated their actions.

In Honduras, Congress and the courts faced a situation where the president, Hugo Chávez-wannabe Manuel Zelaya, was trampling on the rule of law and separation of powers by initiating an illegal campaign to rewrite the Honduran constitution in his favor. Their hand forced, they initiated an admittedly bit of rough justice by kicking him out of the country. (He was subsequently allowed to return.)

In Paraguay, Congress and the courts moved against President Lugo because…well, it appears they just didn’t want him around anymore. Not accused of any official wrongdoing, he was impeached on the grounds of “poor performance” in a political squabble that had been building up for months. (The actual pretext for the lopsided impeachment vote was his perceived lackluster response to a recent deadly clash between landowners and squatters northeast of Asunción.)

There is a world of difference between the two situations and that is why the Paraguay situation is a more worrisome blow to the health of regional democracy. “Poor performance” is obviously a rather thin reed on which to hang a process as weighty as the impeachment of a president.

- Florida’s ‘Foreign Policy’ Laws Aimed at Cuba Meet a Mixed Fate in Court

- Convicted Spy Asks to Serve Probation in Cuba

- DREAM Graduation 2012: Undocumented Youth March in Washington D.C.

- Best Sports Pix of the Week

- Best Pix of the Week

- Prisoners Rule the Jails of Honduras

- New York City Immigrant Parade Draws Few Latinos

Instead, Paraguay’s two traditional parties merely seized an opportune moment to rid themselves of a president who to them had lost his usefulness, even though he had only nine months left in his term. (It has indeed been a rocky term for Lugo, a former Catholic priest and political outsider, who alienated both his political allies and his base, was mired in personal scandals, and really couldn’t get much done politically. But, nevertheless, he never aspired to be a “Paraguayan Chávez.”)

The fact is, what happened in Paraguay constitutes a dangerous lowering of the bar for an action as serious as deposing an elected president. For all his faults, Lugo did nothing egregious to warrant his impeachment, unlike Zelaya, whose lawlessness forced it.

It remains to be seen what the regional fallout will be. The Obama administration has been cautious in its statements so far. But, frankly, there is only so much anyone can do in response to Lugo’s ouster. Paraguay is poor, landlocked, and already rather isolated in the region, so it’s unlikely to be bullied into returning Lugo to office and economic reprisals are unlikely to accomplish much. The best course is simply to let it move on with its affairs.

But moving on regionally is a different matter. One hopes that the situation in Paraguay serves as a clarion call for a more robust regional response among responsible governments to the degradation of democracy witnessed over the past several years in several countries.

So far, the biggest outcry about Lugo’s ouster are being made by Chávez and his radical populist clique, which is the height of irony since Lugo’s summary impeachment is merely the mutant offspring of their own dedicated campaigns to manipulate, bend, and break democratic institutions for their own narrow political ends.

No doubt they are terrified of the prospect of the Frankenstein monster devouring its creators, but there would be no satisfaction in watching that happen. Not if the price is the further erosion of regional democracy.

What’s needed instead is a concerted regional effort to perhaps create under the auspices of the Organization of American States a special unit to monitor threats to democracy, publicize those threats, and perhaps open the way for high-level intervention to try and defuse political crises such as that which has just occurred in Paraguay, because there will be another one given the trend line; the only question is where.

Of course, Chávez and his ilk will noisily oppose any such initiative, because they wouldn’t be able to withstand the scrutiny. But the question for all the other governments in the region is this: are they content with returning to an earlier era of presidents-for-life or, the flip-side, presidents-for-a-day? It’s time to make a stand.