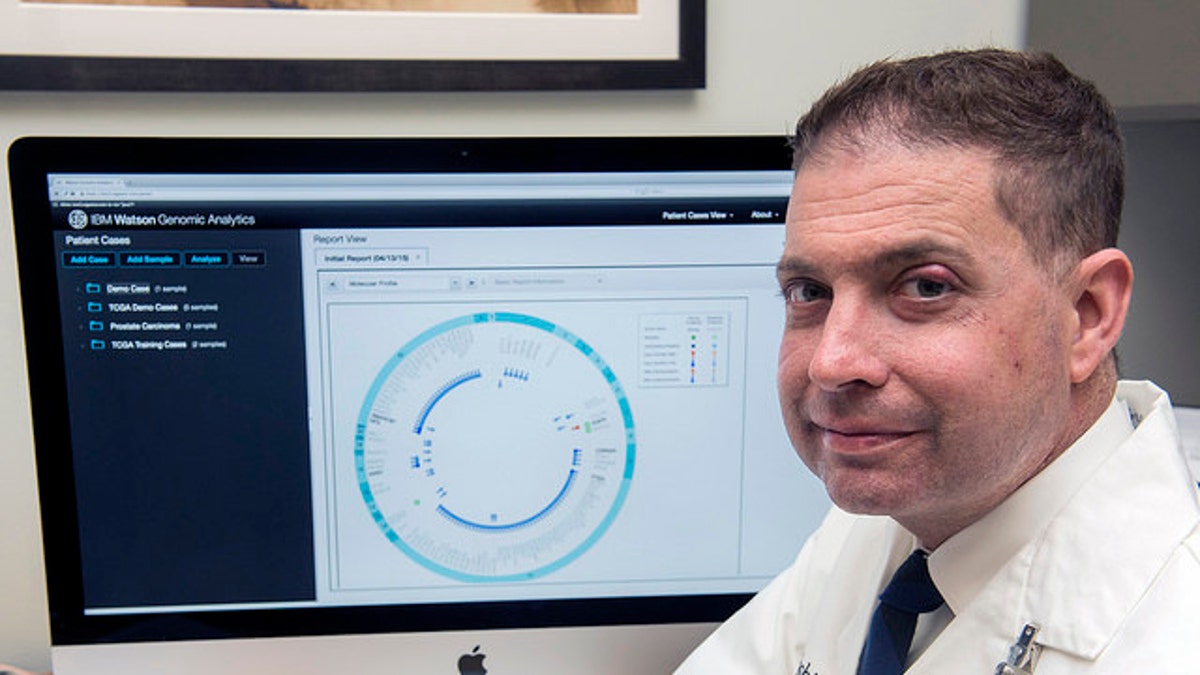

Lukas Wartman, MD, assistant director of cancer genomics at the McDonnell Genome Institute at Washington University in St. Louis, analyzes genomic sequencing data using IBM Watson Genomic Analytics. (Mary Butkus /Feature Photo Service for IBM)

Back in 2003, when he was a fourth year medical student at Washington University in St. Louis looking at a career in oncology, Lukas Wartman was diagnosed with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. For Wartman, the diagnosis was bleak – while this type of leukemia, which affects the blood and bone marrow, is very treatable for children, it often proves fatal for adults. Two years of chemotherapy followed and Wartman went into remission and completed his medical studies. The reprieve was short-lived. By 2008, he relapsed again.

During this second relapse Wartman was approached by The Genome Institute about being part of a research study to have his entire genome sequenced. Through careful analysis of Wartman’s RNA, it was found that a gene known as FLT3 was found in a higher level than average. Sutent, a drug that targets the FLT3 gene for people who have kidney cancer, was determined to be the best course of treatment. Wartman went into remission for a third time. He is now cancer free, and it is safe to say that genomics saved Wartman’s life.

For Wartman, a doctor who is perhaps even more acutely aware of the effectiveness of genomics research than others, the announcement that IBM Watson would be partnering with 14 leading cancer institutes to advance genomics research resonated strongly. Wartman, who serves as the assistant director of cancer genomics at Washington University’s McDonnell Genome Institute, was on hand May 5 at the first annual World of Watson event in Brooklyn, New York to help announce the new partnership.

As with much of the work that IBM’s cognitive computing system has been participating in – Watson has dipped its toes into everything from education to cooking — this new genomics initiative marks a way to leverage big data to simplify an often complex process, such as making personalized cancer diagnoses.

According to IBM’s press release, the genome for one patient equals about 100 gigabytes of data. It’s a vast amount of information for a human doctor to sift through. With Watson quickly analyzing this information, IBM executives view this as being one of the cornerstones of the broader Watson Health initiative.

“Together, we will change the face of healthcare,” IBM CEO Ginni Rometty proudly declared during the World of Watson event in the Brooklyn Navy Yard.

For Wartman, who started having informal conversations with IBM upon hearing about Watson’s move into the health sector, the response to this new program has been “overwhelmingly positive.”

“Moving forward, I think now it’s time for us to show that we can use this platform successfully, get away from the hype, and get the evidence to show that this is effective,” Wartman told FoxNews.com. “This is a great first step.”

Wartman said that the ability to have easily accessible vast amounts of data that can be used – in a HIPAA-compliant way – to shed light on a disease that manifests itself so differently individual-to-individual is game-changing.

While Watson — with its boundless capacity to learn more and more information – sounds like the ultimate medical professional, Wartman asserted that the computer is not a replacement for doctors.

“This technology is not meant to replace the high standard of care that we already have,” he said. “We are going to learn from this sequencing technology and be able to provide much better prognostic information.”

It is unusual for a patient to survive three relapses as Wartman has, and he acknowledged that many “aren’t as lucky as I have been” and that, hopefully through this technology, “more people can be treated more successfully.”

How can Watson help do this? Wartman suggested that by having a more intimate understanding of each patient’s genetic code, doctors will be able to find more out-of-left-field drugs to target specific cancers. Just as Sutent was deemed the best treatment for Wartman by looking at his RNA, the idea is that Watson can help more physicians make similarly targeted prognoses for more patients.

Over the past few decades, technological advances in medicine have made lightning-fast strides. When Wartman was first treated 12 years ago, he said that the protocol used to battle leukemia didn’t vary much from what was “cutting edge” decades before.

“From a decade ago to now, doctors now have this amazing turnaround time when it comes to interpreting results – it’s tremendously exciting,” Wartman added.

The real end-goal for this kind of development is to make this genetic data as widely available as possible. Essentially, it isn’t just reserved for the big, elite medical institutions like the one in which Wartman both works and was treated. He said that this cognitive computing technology “needs to play an important role in helping to bring this (information) to the wider population.”

For cancer survivors and patients, optimism is always tempered by the fact that “cancer is a really, really, tough disease,” according to Wartman.

“This sequencing technology — using these analytic platforms — gives us a better opportunity to make headway against cancer than ever before,” Wartman said. “Now is the time that we need to think about how we can stay in the fight against cancer, the war against cancer, and keep pushing forward and find ways to continue to make significant improvements in the way we are treating patients.”