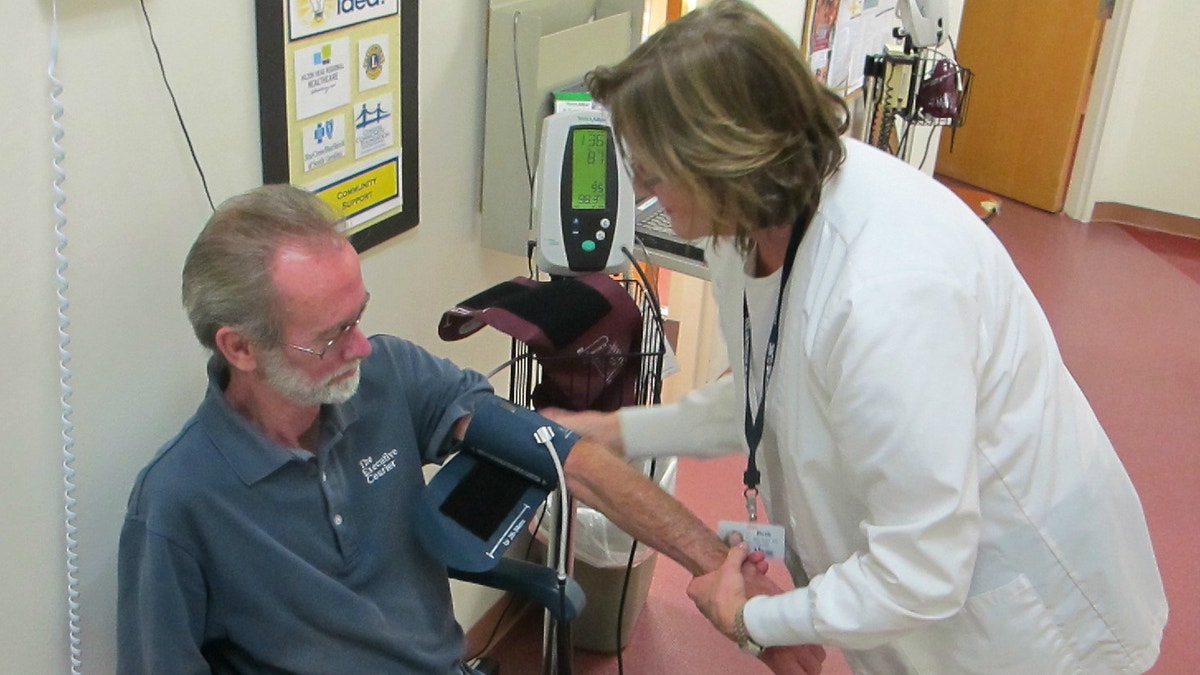

Jim Grant has his blood pressure taken by Beth Heyman at the Volunteers in Medicine Clinic on Hilton Head Island, S.C. The free clinic, staffed by retired physicians and nurses as well as volunteers, has become the model for 96 similar clinics nationwide. Last year, the nation's VIM clinics had 400,000 patient visits. (AP Photo/Bruce Smith)

What began two decades ago on Hilton Head Island as a free clinic using retired physicians and volunteers to care for the working poor has become a model for dozens of similar clinics nationwide. At a time when the nation debates how to pay for care, there are now 96 Volunteers in Medicine Clinics in 29 states.

Thousands of people can be thankful for the network of free clinics nationwide that grew from a model developed in 1994 on this resort by Dr. Jack McConnell in 1994.

The Hilton Head clinic has grown to handle more than 33,000 patient visits a year and offers services that include, among others, dental and eye care and mental health treatment and family practice. Nationally, the network of Volunteers in Medicine clinics had an estimated 400,000 patient visits last year. The new wrinkle in the network is the Affordable Care Act, and even though most patients the clinics treat still wouldn't be able to afford insurance under the law, those who may think of starting their own clinic may wait until the overall effect is better known, said Amy Hamlin, the executive director of the national Volunteers in Medicine based in Burlington, Vt.

Some clinics, like that on Hilton Head use primarily retired physicians. Others are staffed by doctors still in practice who donate their time. All use volunteers for everything from keeping records to cleaning up and raising donations to keep the clinics operating.

"It's really remarkable what they are able to do without any government funding and using volunteers," Hamlin said.

Each clinic is independent but the national group offers help to those who want to start one. It also provides a network where clinics can exchange ideas on everything from getting donated medical supplies to attracting physicians and volunteers.

The Hilton Head clinic operates on an annual budget of just over $2 million, said Lisa Drakeman, the chairman of the clinic's board of directors.

Like other clinics nationwide, the operation depends on a combination of cash donations by supporters as well as in-kind donations of everything from medicines and medical equipment to cleaning supplies and children's books for the pediatric clinic. Practicing medical specialists often also offer in-kind or reduced-price services for procedures that can't be done at the clinic.

One day last week the Hilton Head clinic was bustling as usual, with about 100 patients being treated in the first two hours it was open. It is staffed with a roster of 120 doctors, nurses and health professional and 600 other volunteers.

"I enjoy playing golf but I can't play golf five and six times a week," said psychologist Doug Wolter, 75, has served at the clinic almost 15 years, ever since retiring to the resort island from Michigan. For the past 18 months, he has been the director of the clinic's mental health program working three days a week.

He said mental health services are important to the working poor.

"People who are extremely poor have more depression but it's related to their physical situation. They don't have a job and they don't have any money and if you have a propensity toward depression that can really bring it on," he said.

Down the hall, Jim Grant, 60, who works for a courier company, was getting his blood pressure checked. He said he doesn't have money to pay for insurance.

"I just can't afford it. I've been coming here several years and I couldn't live without it," he said. What would he do if the clinic wasn't here? "Go broke, I guess, paying doctor bills or do without," he said.

Dr. Raymond Cox became the new executive director of the clinic last summer and he said one of the goals for Hilton Head is to increase wellness programs, something that should reduce the number of daily clinic visits.

"As much as we think everybody by now should understand these issues, we're finding a lot of these patients have not had that education, about proper diet or proper exercise," he said.

The clinic's dental department is also stressing the importance of checkups and cleanings before the problem deteriorates into decayed teeth or other oral surgery.

"There is still a good deal of fear of going to the dentist. And in our patient population that's fairly common," said Lois Schuhrke, who coordinates the dental department. "We start with little kids when those kids are 2 or 3. They have no fear of the dentist. We catch them early and we work really hard on the preventive dentistry side."