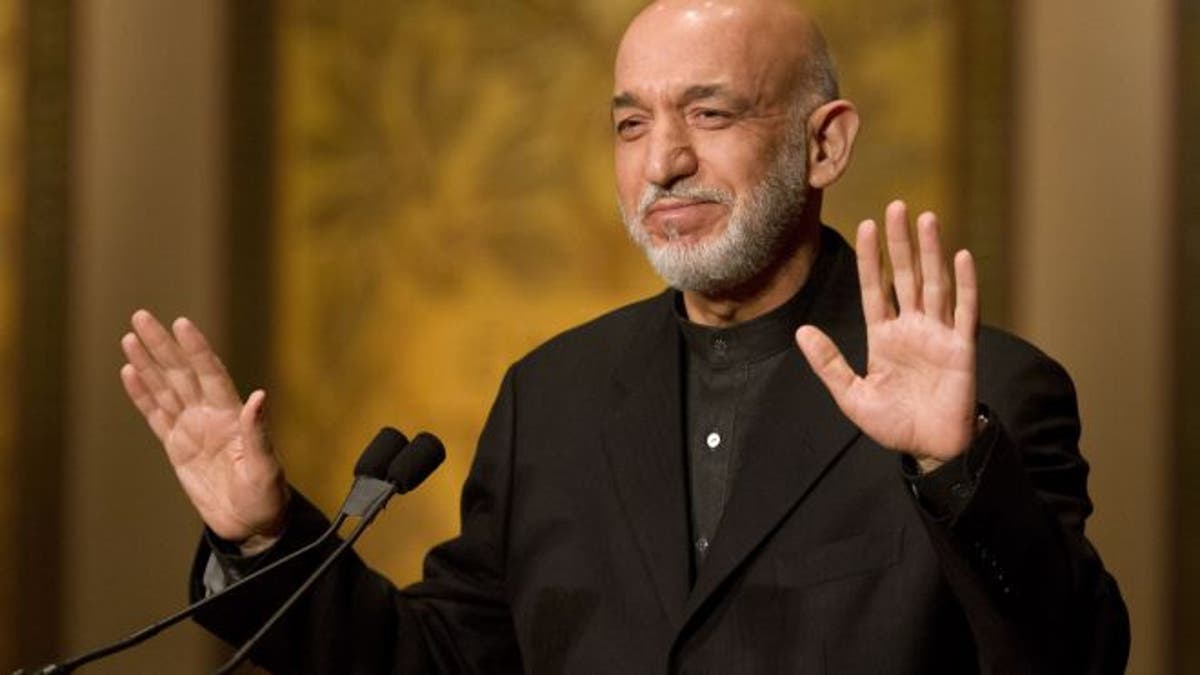

Jan. 11, 2013: Afghanistan President Hamid Karzai gestures for applause to stop before he began his speech at Georgetown University in Washington. (AP)

KABUL, Afghanistan – Afghan political parties united against President Hamid Karzai recently opened talks with the Taliban and U.S.-declared terrorist Gulbuddin Hekmatyar, hoping to broker peace ahead of next year's exit of international combat troops and a presidential race that will determine Karzai's successor, Taliban and opposition leaders have told The Associated Press.

It's the first confirmation that the opposition has opened its own, new channel of discussions to try to find a political resolution to the war, now in its 12th year. And the Taliban too seem to want to move things forward, even contemplating replacing their top negotiator, two senior Taliban officials told the AP.

Reaching an understanding with both the Taliban and Hekmatyar's Islamist militant group, Hezb-e-Islami, would give the opposition, which expects to field a consensus candidate in next year's presidential election, a better chance at cobbling together a post-Karzai government. The alternative to a multi-party government after the 2014 elections, many fear, could signal a return to the internecine fighting of the early 1990s that devastated the capital Kabul.

But with ongoing back-channel discussions and private meetings being held with Taliban interlocutors around the world, it's difficult to know exactly who's talking with whom.

Early last year, Karzai, who demands that any talks be led by his government, said that his administration, the U.S. and the Taliban had held three-way talks aimed at moving toward a political settlement of the war. The U.S. and the Taliban, however, both deny that such talks took place.

Hekmatyar's group has held talks with both the Karzai government and the United States, and a senior U.S. official said the Taliban are talking to representatives of more than 30 countries, and indirectly with the U.S.

The Taliban broke off formal discussions with the U.S. last year and have steadfastly rejected negotiations with the Karzai government, which they view as a puppet of foreign powers.

News about the opposition group's new avenue of talks comes amid Karzai's latest round of verbal attacks on the United States, which have infuriated some of his allies in Washington and confused some of his senior advisers.

In recent weeks, Karzai has accused the U.S. of colluding with the Taliban to keep foreign troops in Afghanistan and has attacked the Taliban for talking to foreigners while killing Afghan civilians in their homeland. Earlier this month, Karzai accused the West of trying to craft an agreement between the Taliban and his political opponents and vowed to oppose the opening of a Taliban office in Qatar if it was used for talks with anyone other than his government. The U.S. has denied the allegations.

The Afghan president also has stepped up his rhetoric against his political opponents, trying to paint them as American pawns in a grand U.S. scheme to install a government of its liking when the United States and the NATO withdraws its combat troops by Dec. 31, 2014. The troop withdrawal and presidential elections are two major events observers fear could bring instability to Afghanistan.

Trying to put its stamp on the future, the opposition — united under a single banner called the Council of Cooperation of Political Parties — say it has reached out to both the Taliban and Hekmatyar, a one-time U.S. ally who is now listed as a terrorist by Washington.

In addition to getting the blessing of Taliban chief Mullah Mohammad Omar, any peace deal would have to be supported by Hekmatyar, who has thousands of fighters and followers, primarily in the north and east. Omar and Hekmatyar are bitter rivals, but both launch attacks on Afghan government and foreign forces and both have suspended direct talks with the U.S., saying they were going nowhere.

"We want a solution for Afghanistan ... but every step should be a soft one," said Hamid Gailani, a founding member of the united opposition. "We have to start somewhere."

The opposition group is full of political heavyweights.

There are former presidential candidates, Abdullah Abdullah and Ali Ahmed Jalali — both of whom were said to be Washington's preferred candidates in the last presidential election in 2009. There's also Rashid Dostum, who leads the minority Uzbek ethnic group and Mohammed Mohaqiq, the leader of another minority ethnic group called the Hazaras. Also in the group is Ahmed Zia Massoud, a former Afghan vice president and the brother of anti-Taliban fighter Ahmed Shah Massoud, the charismatic leader of the ethnic minority Tajiks who died in an al-Qaida suicide attack two days before the Sept. 11 attacks that provoked the U.S. invasion of Afghanistan in late 2001.

A senior official with Hekmatyar, who is familiar with the many negotiating threads of his organization, confirmed that representatives have met with Karzai's opposition. He said the talks were nascent, but refused to give additional details. He spoke on condition of anonymity because of the sensitivity of the negotiations.

Taliban spokesman Zabiullah Mujahid denied that the Taliban were talking with the opposition group. But a second Taliban official confirmed that the Taliban has been in contact with opposition members in Kabul. The official spoke on condition of anonymity because he was not authorized by the movement to speak to the media.

Gailani said the opposition group is in discussions with Taliban interlocutors who are close to Omar. He refused to identify them, saying it could put them at risk with the both the Afghan government and other members of the Taliban opposed to peace talks.

Hekmatyar has laid out a 15-point plan for Afghanistan's future that calls for a broad-based government, nationwide elections, an interim administration and a series of election reforms.

The Taliban have been less clear about how they envision a future Afghanistan. However, late last year Omar, the one-eyed, reclusive leader of the Taliban, issued a statement in English that seemed unusually conciliatory and flexible. In the statement, which was widely circulated by the Taliban's media wing, Omar said the Taliban neither wanted to monopolize power nor start another civil war like the one that evolved after the Russian-backed communist government fell in 1992.

"As to the future political destiny of the country, I would like to repeat that we are neither thinking of monopolizing power nor intend to spark off domestic war, but only try that the future political fate of the country must be determined by the Afghans themselves without any interference from big countries and neighbors, and it must be Islamic and Afghan in form," said Omar in his statement.

The United States largely ignored the statement when it was issued, a senior U.S official told the AP. He said the statement was examined belatedly.

A second senior U.S. official, who is familiar with Washington's attempts at talking with the Taliban, said there have been "no, no, no direct contacts of the U.S, with Taliban since January 2012."

Both U.S. officials spoke on condition of anonymity because of the sensitivity of the subject.

Apparently frustrated by the lack of any progress in talks with the U.S., two Taliban officials told the AP that the religious movement's governing council, was contemplating removing Tayyab Aga — special assistant to Omar during the Taliban's rule — as their lead negotiator because he "could not achieve the expected results." They did not explain what results have been expected, but the militant group has demanded the release of five senior Taliban figures being held at the U.S. military prison in Guantanamo Bay, Cuba, — something the U.S. has so far rejected to do.

Mullah Abbas Akhund, the Taliban's health minister, is being tapped as Aga's replacement, according to the two Taliban officials, who spoke anonymously because they feared repercussions from other Taliban members for speaking to the media. A veteran Taliban, Akhund escaped when the Taliban fled Kabul in November 2001 by hiding among Afghanistan's kuchis, or nomadic tribes, that roam the country relatively unhindered by any faction in the conflict.

Talks with the U.S. were temporarily scuttled in early 2011 by Afghan officials who were worried that the secret, independent talks would undercut Karzai. They quietly resumed with each side seeking small signs of cooperation, but the Taliban shut down all talks with the United States after it refused to release its colleagues from Guantanamo Bay.

A third U.S. official, also speaking anonymously because of the secret nature of some meetings, said some unofficial contacts between the Taliban and U.S. officials have taken place in the Middle East. The official refused to identify the country or the Taliban interlocutor.

The Taliban have also sought to make their negotiating team more palatable to the West by including Qari Din Mohammed, an ethnic Tajik from Afghanistan's northern Badakhshan province, the two Taliban officials said. The Taliban are predominantly Pashtun, the majority ethnic group that dominates southern and eastern Afghanistan.

But even as the Taliban's governing council contemplates ways of gaining traction on talks, there are some in the militant group who oppose them altogether, according to members of the Taliban as well as Western diplomats.

Some younger members of the group believe they are winning the war and see negotiations as a sell-out. The Taliban's top military man, Zakir Qayyum, a former Guantanamo prisoner, is dead set against the talks, Taliban and Western diplomats say, but even members of the military council say Qayyum will back down if Omar orders up a peace deal.

____

Kathy Gannon is AP Special Regional Correspondent for Afghanistan and Pakistan and can be followed on www.twitter.com/kathygannon