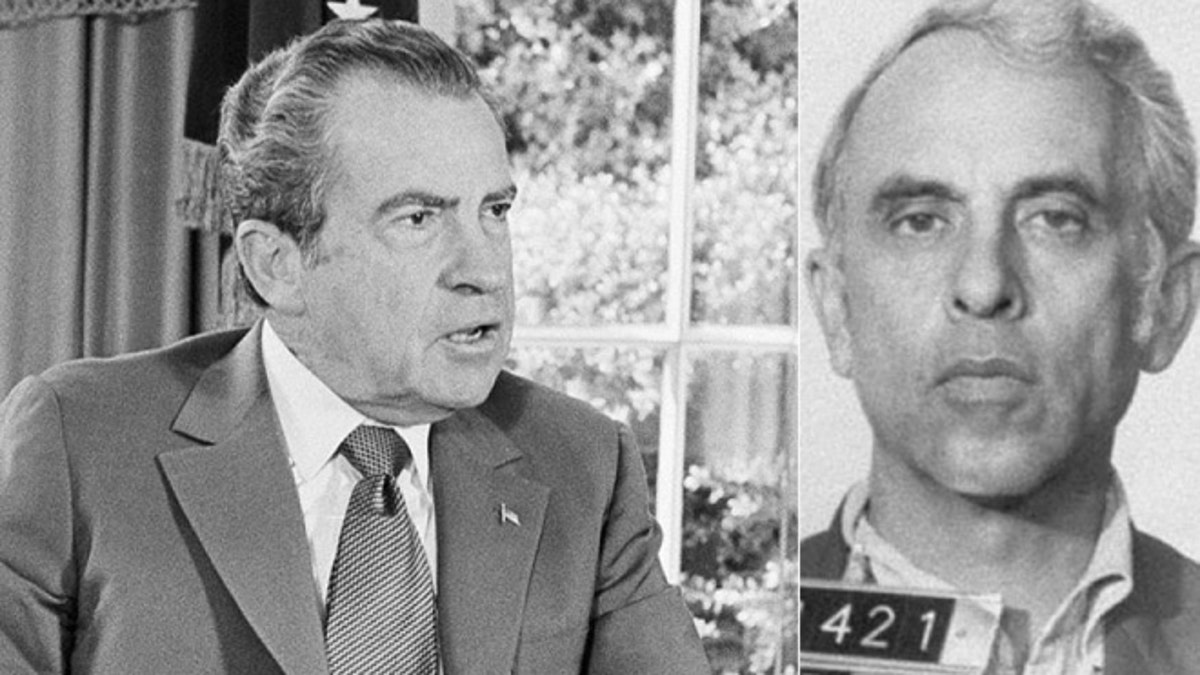

President Richard Nixon, left, and Watergate burglar and CIA agent, Eugenio Martinez. (Photos: Associated Press)

Forty-four years ago, a handful of men broke into an office in Washington, D.C., and two years later the president of the United States resigned.

There have always been questions about the Central Intelligence Agency’s involvement in the most famous burglary in the history of the U.S., at the Watergate Hotel offices of the Democratic National Committee in June 1972. Likewise, the connection to the Cuban exile community in South Florida has long been noted.

Now, a report released thanks to a Freedom of Information request has revealed that one of the five men arrested at the Watergate complex, Eugenio Martinez, was both: a Cuban exile and a CIA agent.

The information, requested by the conservative watchdog organization Judicial Watch, was made public on Tuesday.

The CIA’s internal 155-page secret history of its involvement in Watergate was begun by the inspector general’s office in 1973 and was never completed.

“We had heard that historians considered this a sort of Holy Grail-type document, a big missing piece of the puzzle, so we filed a Freedom of Information request on it,” Chris Farrell, Judicial Watch's director of investigations, told the Miami Herald. “And when the CIA didn’t respond, we sued, which is unfortunately the only way public records cases get solved these days.”

Watergate investigators long suspected that Martinez, a CIA informant in Miami who was known as “Musculito” – “Little Muscle” – who fed the agency a steady stream of information about the Cuban exile community, was an active operative of the agency.

Back in 1973, they asked the spy agency for Martinez’s full file, but were refused.

According to the newly-released document, the CIA’s top lawyer at the time, John S. Warner, told prosecutors that “under no circumstances would the Agency give up all records relating to the Agency’s relationship with Martinez. Warner explained why such a request was difficult for the Agency —the breaching of trust of an agent.”

That is the first known reference by a CIA official to Martinez as being “an agent” rather than an informant, and it shows the lengths to which the agency would go to protect him.

At the time of the arrest, Martinez attempted to hide from the police a key that FBI investigators determined opened the desk of DNC secretary Ida “Maxie” Wells, whose office phone was the only one that the burglars successfully wiretapped during the break-in.

There has never been a clear explanation of how Martinez came to be in possession of the key.

No other burglar had such a key and it has never been satisfactorily explained as to how or why Martinez came into possession of it. The other Cuban exile among the burglars, Virgilio Gonzalez, was a locksmith whom Martinez, in a first-person account of the break-in published in Harper’s Magazine in 1974, described as “our key man.”

Despite that article, Martinez, now 94 and living in Miami, has remained quiet about Watergate ever since. He served 15 months in prison and was paroled in 1974.

He became a car dealer, and, in 1983, Ronald Reagan pardoned him for his role in the burglary.

An acquaintance told the Miami Herald, “If you see him at a party and ask even a casual question, he just sort of smiles and changes the subject.”

The report released to Judicial Watch doesn’t explain the key.

Farrell told the Herald that it appears that the CIA didn’t turn over eight appendices that are referenced in the document. “We’re talking to them about that,” he told the paper. “If we have to go back to court to get the rest, we will.”