U.S. Army Private 1st Class Raymond W. Maker, left, and the key he says he took from Verdun, France, around the end of World War I. His grandson, Bruce Norton, is in France today to return the key back to the town.

One hundred years ago on this date, U.S. Army Private 1st Class Raymond W. Maker wrote in his diary “today is one of the happiest days of my life."

“The War is off, thank God. And all the boys have gone about half mad with joy. Bands are playing all day and at night all kinds of flares in the sky,” he beamed, capturing the relief felt among Allied forces as World War I officially came to an end.

It was a thrilling moment for Maker who, during the war, had been hit with mustard gas from the German army, wounded by artillery fire during the Muese-Argonne offensive – the deadliest battle in U.S. military history – and later went on to earn a Purple Heart for his service.

And now, a century later, on this Veterans Day – marking the 100th anniversary of the armistice that ended The Great War – his grandson, Bruce Norton, is in France retracing Maker’s footsteps and honoring him by returning a key his grandfather took during the war. Norton is joining the many Americans remembering the heroics of family members from generations past.

“My grandfather never spoke about the war to me, and it was only after his death that war stories were told at family gatherings about his service in France,” Norton, a former Marine and military author who is writing a book about Maker’s service, told Fox News.

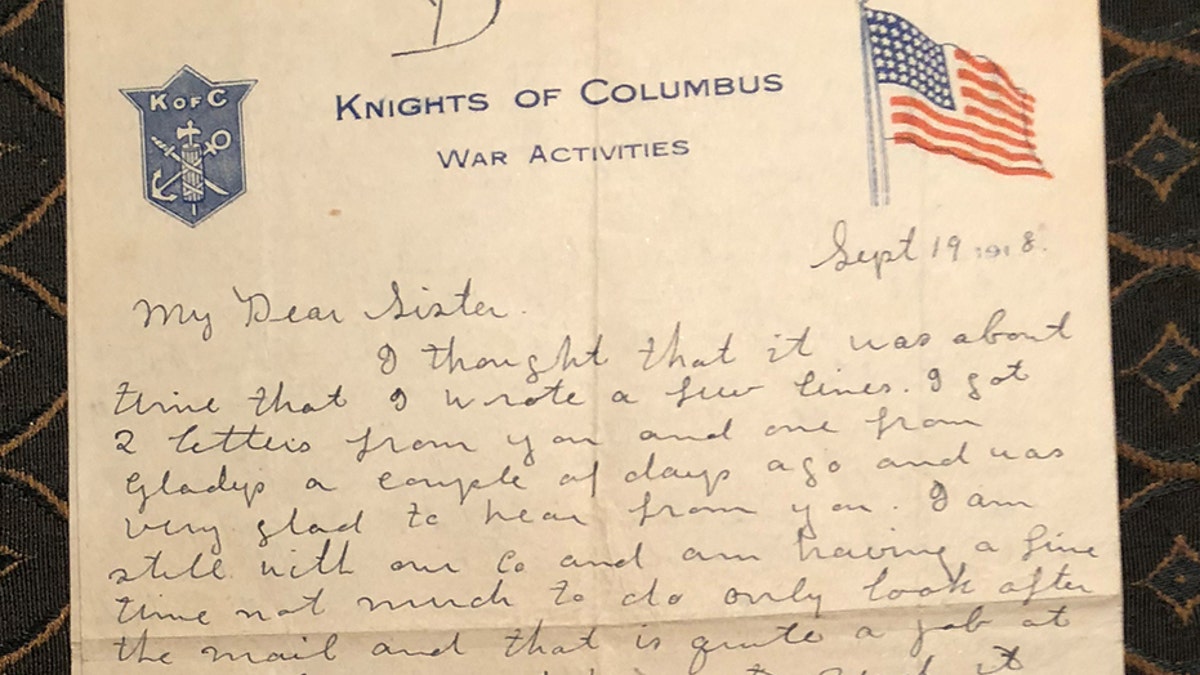

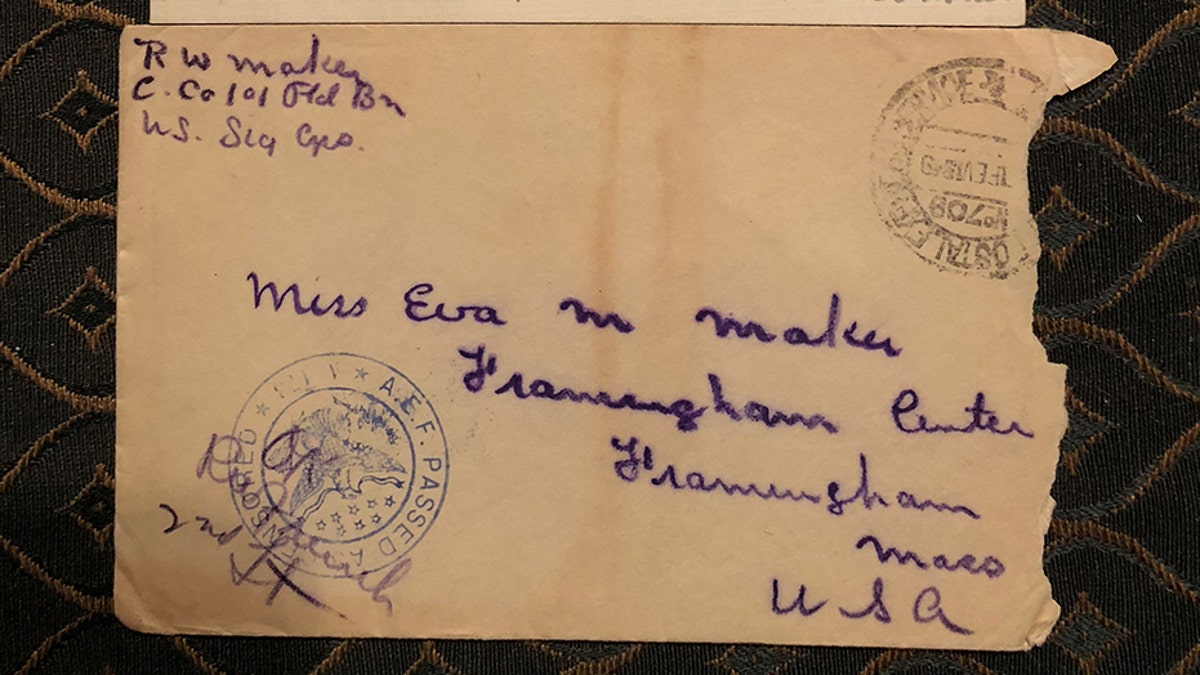

The upcoming book, titled “Letters of a Yankee Doughboy,” contains more than 120 letters Maker wrote from the front lines of the war to his family in Framingham, Mass.

Maker would often write home to his family during World War I. He is pictured here as a young boy, on the far right of the bottom row. To his side, from right to left, are his stepsister Harriet, sister Eva and brother Clifford (Kip). His uncle Edward, wearing a Union Army uniform, is second from the left in the middle row, next to Edward's brother, Andrew. Both of those men fought for 19th Maine Regiment during the Civil War. Maker's father, Winfield, is standing in front of the bicycle on the far right. (Courtesy Bruce Norton)

Norton said he was given the letters in a box in 1992 while visiting his mother in Rhode Island. But something else inside that box became integral to his current trip to France this Veterans Day – a key that Maker took from a gate in the town of Verdun shortly after the war ended, which Norton is returning today to its rightful home.

“All I want to do is correct a wrong,” he told Fox News.

The story of how the iron key ended up in Norton’s possession began in 1914, when Maker joined the Massachusetts National Guard. Three years later, his unit was activated and became the U.S. Army’s 26th Infantry Division, which set off to France and encountered heavy combat.

“I hope that it won’t be so very long before I see you all again and do not lose heart if you do not hear from me very often because I may be in places where I cannot get a chance to write but will every time I can,” Maker wrote home on Oct. 6, 1917, in one of his first letters to his sister, addressed to “My Dear Eva & all the folks.”

One of the letters Maker wrote. (Courtesy Bruce Norton)

Over the next few years, Maker would – sometimes on a daily basis – pen letters to his family describing his World War I exploits as a wireman, who Norton says would “go out after these barrages and string communication wire between positions.” He also kept a diary with shorter entries.

“The fellow that was with me and myself laid in a large shell hole for about 30 hours running a telephone station, and then we got out and we went into the woods and found a dugout, and being about all in, we fell right to sleep and then the Boche started shooting over gas,” Maker wrote to his brother Kip on July 27, 1918, recalling the moments he was gassed by the Germans in France.

“We did not hear the shells and a fellow came running in with his mask on and yelled, “Gas, Gas.” Well, Kip, we put on our masks but a little too late because it had gotten us before, while we were asleep. And if that fellow had not yelled when he did, I would not be writing to you now, I guess,” he added.

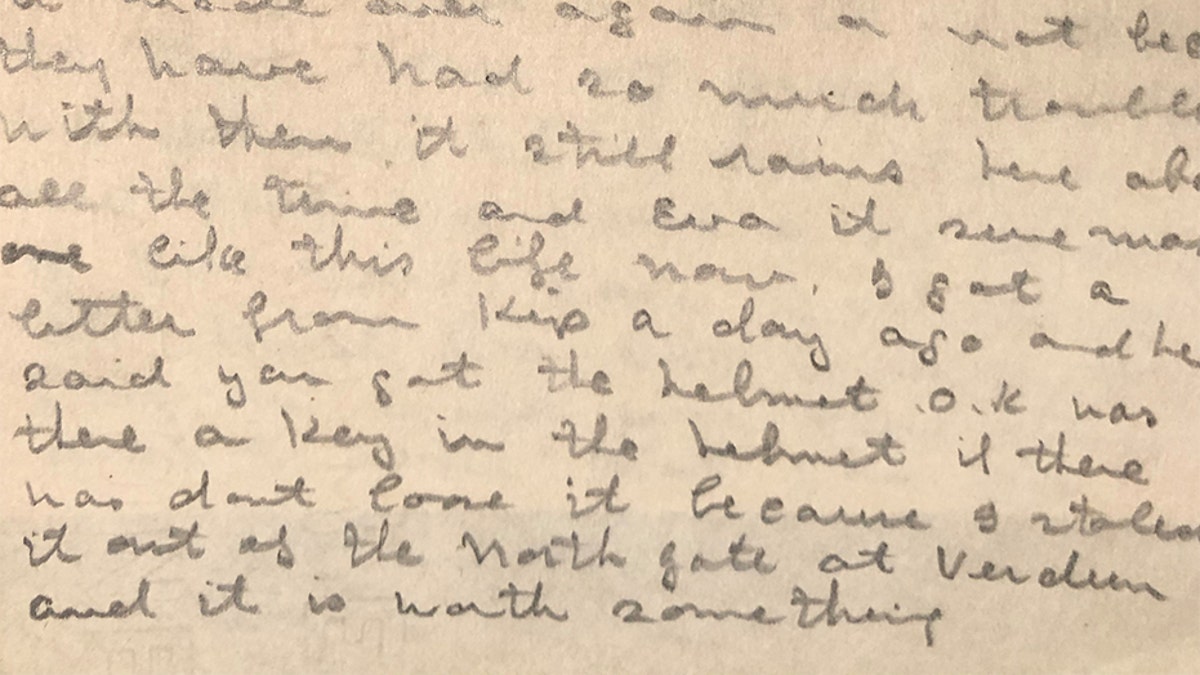

Maker mentions the key he took from Verdun in a letter to his sister, Eva. (Courtesy Bruce Norton)

Maker mentioned in his writings about being in Verdun in November of that year, the same month of his 26th birthday and the signing of the armistice. He noted in a past letter of his travels about amassing a “pile” of German helmets from the battlefields and a “lot of German stuff,” but it wasn’t until January 1919 that he made mention in his writings of the key from Verdun.

“I got a letter from Kip a day ago and he said you got the helmet OK. Was there a key in the helmet? If there was don’t lose it because I stoled it out of the north gate at Verdun and it is worth something,” Maker wrote to Eva.

A 1956 article by the Providence Sunday Journal, reprinted in a draft version of Norton's book and provided to Fox News, references the key and further explains that “besides being six inches long and heavy, [it] has the added value of belonging to the historic North Gate of the Verdun Citadel where the German advance was squelched.”

The article makes mention of a Mrs. Charles A. Post, a Rhode Island resident who traveled to Verdun that year to return the key she received from Maker, who in response was given “an official certificate from the senator-mayor of Verdun for this unexpected addition to the battle site’s historic collection.”

Norton was able to learn more about his grandfather's life through the dispatches that were sent home from the front lines. (Courtesy Bruce Norton)

Except, decades later, Norton says he found out the events described in that article were not all that it seemed.

In an excerpt of Norton’s book, he writes “in October, 1992, during a visit to Rhode Island, my mother brought out a box from within her closet and said, “I have some things I want you to have. Here are all of your grandfather’s letters from World War One, and this is the key to the North Gate of Verdun, France, the one that Daddy mailed back to Aunt Eva.

“In 1956, your grandfather gave a key to a lady, a Mrs. Post, who was traveling back to France and she presented that key to the mayor of Verdun, but what she did not know was the key that Daddy gave to her was an ornate iron key a friend of his had made by the Providence Casting Company in North Providence,” the excerpt adds.

The real key presumably exchanged hands amongst Maker’s family members in the years following World War I. Maker died in 1964 after a severe heart attack and stroke. It is not immediately clear today where the gate stood in Verdun in which the key was taken from.

The key will be accepted today at the Verdun Memorial in France.

But Norton is now meeting today with Thierry Hubscher, the director of the Verdun Memorial, to return it, a spokesperson there confirmed to Fox News. The Memorial says it may put the key into an exhibit about the Americans’ arrival in the region.

“We are particularly honored that Major Bruce Norton chose our establishment for the symbolic return of the key to an important site of the town of Verdun,” Hubscher told Fox News in an email. “This story is absolutely incredible. This key will have taken a journey of over 10,000 kilometers before coming back to its place of origin 100 years later.”