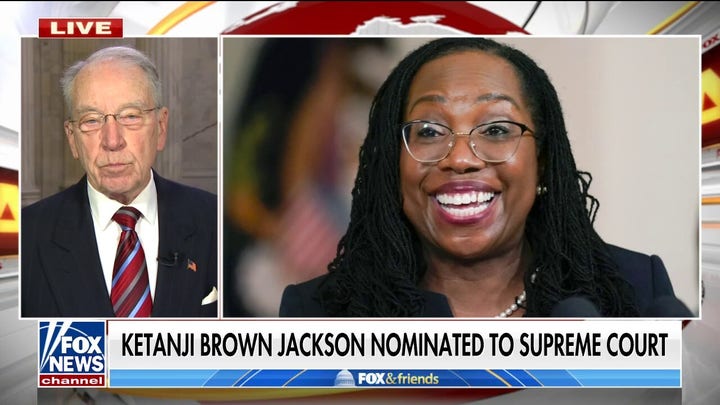

Gowdy: The Supreme Court confirmation process should be thorough, rigorous, and fair

'Sunday Night in America' host reflects on past confirmation hearings ahead of the Senate's questioning of Ketanji Brown Jackson.

There are lots of ways to raise Cain.

Cousins raise Cain at family reunion picnics. Shareholders raise Cain at board meetings over bad earnings reports. Basketball coaches raise Cain with referees on the sideline.

But nobody raises Cain like the Senate at the confirmation hearing of a Supreme Court justice.

Granted, this doesn’t happen every time a Supreme Court nominee goes before the Senate for confirmation.

But senators and activists on both sides have raised a lot of Cain at recent confirmation hearings.

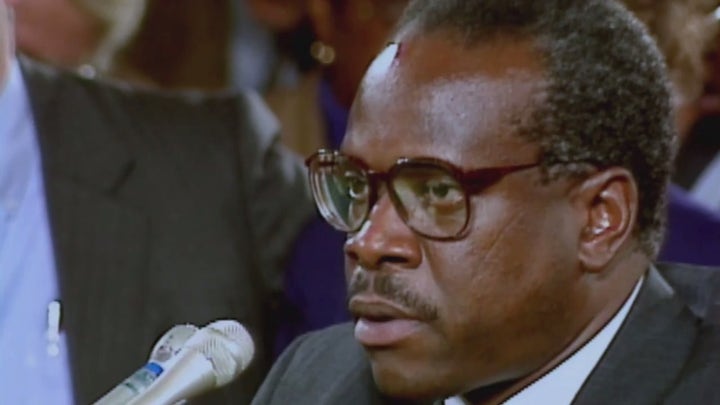

The confirmation hearings for Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas in 1991 and Supreme Court Justice Brett Kavanaugh in 2018 practically raised Cain. The failed confirmation fights involving nominees Robert Bork and, briefly, Douglas Ginsburg in 1987 came close.

But other Supreme Court confirmation hearings are tame. To be clear, they may not appear as bucolic as a warm spring day with "Morning Mood" by Edvard Grieg playing in the background. But despite the raucous affairs to confirm Thomas and Kavanaugh, fervid confirmation hearings are the exception, not the rule.

But let’s explore why some of these confirmation hearings erupt in chaos.

Legislative. Executive. Judiciary. The nomination of a Supreme Court justice fuses all three branches of government into a symbiotic, political ballet. That mixture is rare in American politics.

A lifetime appointment of a justice can shift a nation over the course of his or her term.

So much is at stake. And that’s why both sides sometimes go for broke over a given nominee.

Thomas seemed to be on track for confirmation when his hearings initially closed in September 1991. But that was before law professor Anita Hill leveled salacious charges of sexual harassment at Thomas. The Senate Judiciary Committee, chaired at the time by then-Sen. Joe Biden, re-opened the hearings.

And hell was thusly raised.

"This is a circus. It’s a national disgrace," fumed Thomas. "It is a high-tech lynching for uppity Blacks."

Every network took Thomas’ hearings live. The public: transfixed. CBS owned the rights to the Major League Baseball playoffs that fall. CBS even briefly debated forgoing the national pastime and showing the hearings instead.

The Senate closed its hearings in early September 2018 for Kavanaugh. But the Senate soon found itself on a Miltonian bridge over chaos when Christine Blasey Ford accused Kavanaugh of sexually assaulting her nearly four decades earlier when they were in high school.

SUPREME COURT NOMINEE KETANJI BROWN JACKSON: 10 THINGS YOU MAY NOT KNOW

"When you see (Supreme Court Justices) Sotomayor and Kagan, tell them that Lindsey said hello because I voted for them. I would never do to them what you've done to this guy," erupted Sen. Lindsey Graham, R-S.C., practically spitting his words at Democrats on the dais. "Boy, you all want power. God, I hope you never get it."

After Thomas’ confirmation, a set of rather vanilla hearings unfolded for the late Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, Justice Stephen Breyer, Chief Justice John Roberts and Justices Samuel Alito, Sonia Sotomayor, Elena Kagan, and Neil Gorsuch.

Gorsuch’s hearing was not rambunctious, but his nomination was supercharged. That’s because Democrats believed the seat Gorsuch would soon occupy should have gone to current Attorney General Merrick Garland. President Obama nominated Garland for the high court after the death of Justice Antonin Scalia in early 2016. But Republicans refused to grant Garland a hearing. When President Trump took office and nominated Gorsuch, the GOP gave Gorsuch a hearing and confirmed him. However, current Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell, R-Ky., did have to establish a new procedural precedent to prevent Democrats from filibustering Gorsuch’s nomination.

"We’ll do what’s necessary to confirm Judge Gorsuch to the Supreme Court," said Senate Minority Whip John Thune, R-S.D., at the time, then the Majority Whip.

McConnell argued that the Senate should not confirm Garland in a presidential election year. But even though the confirmation hearing for Justice Amy Coney Barrett went smoothly, Republicans raced to confirm her – just days before the 2020 election.

"I recognize, Mr. Chairman, that this goose is pretty much cooked," mused Sen. Cory Booker, D-N.J., of Republican tactics at Barrett’s hearing.

In fact, Barrett’s hearing was exceptionally calm for two reasons. First, few things could top the spectacle surrounding Kavanaugh’s hearings. Both parties wanted to avoid a repeat. Secondly, the Capitol remained mostly shuttered to the public and demonstrators due to the pandemic.

But this is a look at the dispositions of the confirmation hearings themselves. Most are snoozers. The anomalies were the bedlam that unfolded around hearings for Thomas and Kavanaugh. Instances where hell was actually raised.

But even the mayhem over Kavanaugh’s confirmation was no match for the smut that dominated Thomas’ hearings in 1991.

"I think the one that was the most embarrassing was his discussion of pornography involving women with large breasts and engaged in a variety of sex with different people or animals," testified Anita Hill after she leveled sexual harassment charges against Thomas.

Republican senators sought to undercut Hill’s allegations. They suggested Hill wasn’t credible. Perhaps, they hinted, Hill made the entire thing up. Senators tested insinuation by Hill that Thomas spoke to her about a pubic hair apparently floating around in a soft drink.

"You said you never did say this, ‘Who has put pubic hair on my Coke?’" questioned former Sen. Orrin Hatch, R-Utah, of Thomas.

Republicans thought the Coke story mirrored a scene depicted in the novel "The Exorcist" by William Peter Blatty. Hatch showed up to one hearing, one day, armed with a copy.

"Page 70 of this particular version of ‘The Exorcist’," read Hatch. "‘There appeared to be an alien pubic hair floating around in my gin.’"

Each day of the hearings was more risqué.

Supreme Court nominees never even garnered confirmation hearings until more than 100 years ago. Supreme Court Justice John Harlan received the first "modern" confirmation hearing in 1955. But over time, confirmation hearings evolved into public spectacles – hyped for television.

"A lot of show horse members of Congress treat this as their opportunity to build a national brand," said George Washington University political science professor Casey Burgat. "It is high theatrics."

Former Sen. Kelly Ayotte, R-N.H., served as the "sherpa" for Gorsuch’s confirmation process. Each administration usually fills the sherpa role with someone who is intimately familiar with senators and Senate customs. The sherpa escorts the nominees around to meetings with senators and prepares them for tough questions they may face in their hearings.

Ayotte described "gotcha" questions for nominees as "gamesmanship" in the Senate.

"They’re trying to see if they can trip the nominee up," said Ayotte.

Senators aren’t expecting hearings for Ketanji Brown Jackson to devolve into a hell- raising experience.

So far.

"It will be a serious, dignified process," said McConnell.

CLICK HERE TO GET THE FOX NEWS APP

But there’s a reason why some Supreme Court confirmations are the most intense processes in American government.

The decisions made today by the Senate on a Supreme Court pick echo decades into the future. That’s why confirming a justice is one of the most excruciating exercises in the American political experience.