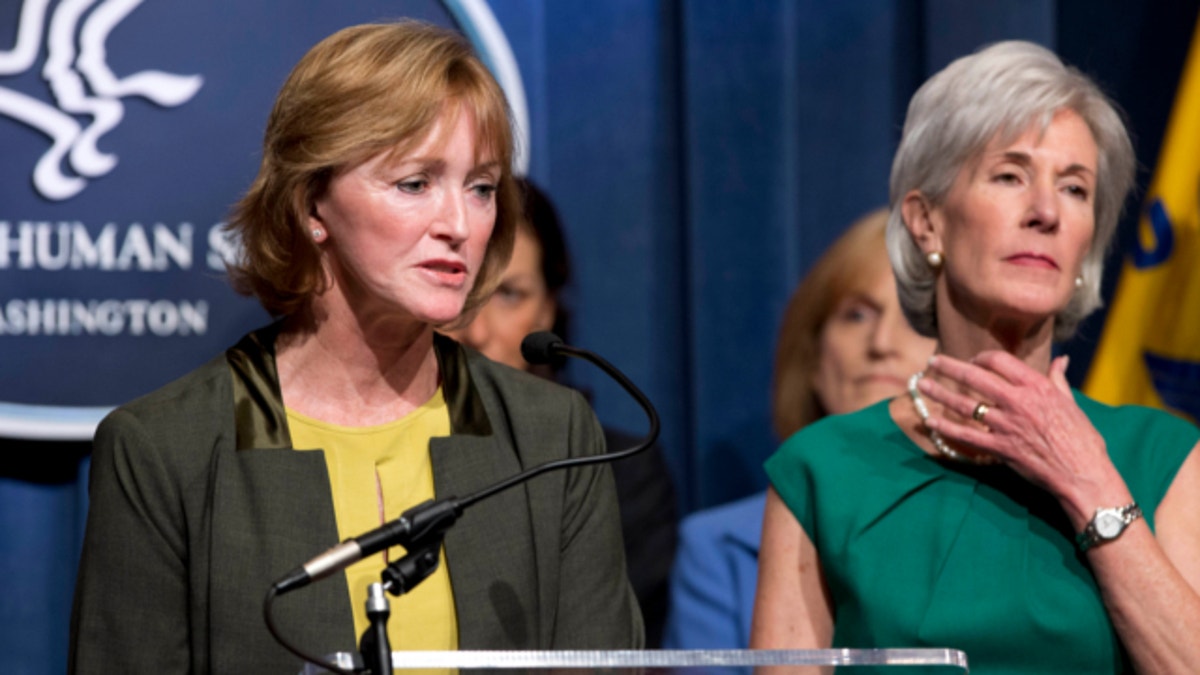

April 10, 2013: Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services Acting Administrator Marilyn Tavenner, left, accompanied by Health and Human Services Secretary Kathleen Sebelius, speaks during a news conference at the Health and Humans Services (HHS) Department in Washington. (AP)

WASHINGTON – Retired as a city worker, Sheila Pugach lives in a modest home on a quiet street in Albuquerque, N.M., and drives an 18-year-old Subaru.

Pugach doesn't see herself as upper-income by any stretch, but President Barack Obama's budget would raise her Medicare premiums and those of other comfortably retired seniors, adding to a surcharge that already costs some 2 million beneficiaries hundreds of dollars a year each.

More importantly, due to the creeping effects of inflation, 20 million Medicare beneficiaries would end up paying higher "income related" premiums for their outpatient and prescription coverage over time.

Administration officials say Obama's proposal will help improve the financial stability of Medicare by reducing taxpayer subsidies for retirees who can afford to pay a bigger share of costs. Congressional Republicans agree with the president on this one, making it highly likely the idea will become law if there's a budget deal this year.

But the way Pugach sees it, she's being penalized for prudence, dinged for saving diligently.

It was the government, she says, that pushed her into a higher income bracket where she'd have to pay additional Medicare premiums.

IRS rules require people age 70-and-a-half and older to make regular minimum withdrawals from tax-deferred retirement nest eggs like 401(k)s. That was enough to nudge her over Medicare's line.

"We were good soldiers when we were young," said Pugach, who worked as a computer systems analyst. "I was afraid of not having money for retirement and I put in as much as I could. The consequence is now I have to pay about $500 a year more in Medicare premiums."

Currently only about 1 in 20 Medicare beneficiaries pays the higher income-based premiums, which start at incomes over $85,000 for individuals and $170,000 for couples. As a reference point, the median or midpoint U.S. household income is about $53,000.

Obama's budget would change Medicare's upper-income premiums in several ways. First, it would raise the monthly amounts for those currently paying.

If the proposal were already law, Pugach would be paying about $168 a month for outpatient coverage under Medicare's Part B, instead of $146.90.

Then, the plan would create five new income brackets to squeeze more revenue from the top tiers of retirees.

But its biggest impact would come through inflation.

The administration is proposing to extend a freeze on the income brackets at which seniors are liable for the higher premiums until 1 in 4 retirees has to pay. It wouldn't be the top 5 percent anymore, but the top 25 percent.

"Over time, the higher premiums will affect people who by today's standards are considered middle-income," explained Tricia Neuman, vice president for Medicare policy at the nonpartisan Kaiser Family Foundation. "At some point, it raises questions about whether (Medicare) premiums will continue to be affordable."

Required withdrawals from retirement accounts would be the trigger for some of these retirees. For others it could be taking a part-time job.

One consequence could be political problems for Medicare. A growing group of beneficiaries might come together around a shared a sense of grievance.

"That's part of the problem with the premiums -- they simply act like a higher tax based on income," said David Certner, federal policy director for AARP, the seniors lobby.

"Means testing" of Medicare benefits was introduced in 2007 under President George W. Bush in the form of higher outpatient premiums for the top-earning retirees. Obama's health care law expanded the policy and also added a surcharge for prescription coverage.

The latest proposal ramps up the reach of means testing and sets up a political confrontation between AARP and liberal groups on one side and fiscal conservatives on the other. The liberals have long argued that support for Medicare will be undermined if the program starts charging more for the well-to-do. Not only are higher-income people more likely to be politically active, they also tend to be in better health.

Fiscal conservatives say it makes no sense for government to provide the same generous subsidies to people who can afford to pay at least some of the cost themselves. As a rule, taxpayers pay for 75 percent of Medicare's outpatient and prescription benefits. Even millionaires would still get a 10 percent subsidy on their premiums under Obama's plan. Technically, both programs are voluntary.

"The government has to understand the difference between universal opportunity and universal subsidy," said David Walker, the former head of the congressional Government Accountability Office. "This is a very modest step towards changing the government subsidy associated with Medicare's two voluntary programs."

It still doesn't sit well with Sheila Pugach. She says she's been postponing remodeling work on her 58-year-old house because she's concerned about the cost. Having a convenient utility room so she doesn't have to go out to the garage to do laundry would help with her back problems.

"They think all old people are living the life of Riley," she said.