The border isn’t a barrier to Dr. Ariel Ortíz Lagardere.

A bariatric (i.e., weight loss) surgeon who grew up and received his medical training on both sides of the U.S.-Mexico border, Ortíz is a California resident while the state-of-the-art facility he started and runs, the Obesity Control Center, is in Tijuana. “I’m puro Chicano,” the 47-year-old told Fox News Latino.

Despite not being affiliated with its manufacturer beyond as a medical consultant, Ortíz has become the face for a new medical device – not approved in the U.S. by the Food and Drug Administration – called Obalon, which has produced some eye-popping weight loss numbers during trials.

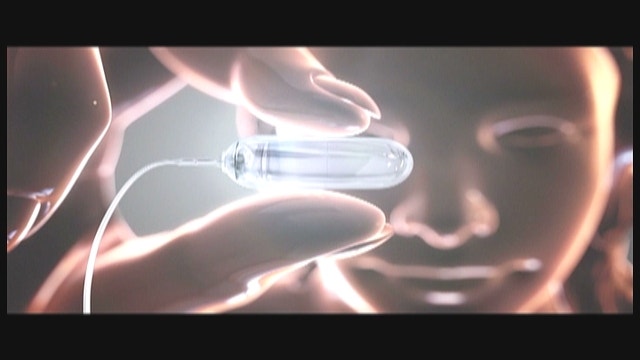

Obalon is a balloon made of a polymer film packed inside a capsule that’s attached to a long tube. A patient – preferably one who is clinically obese, with a body mass index of 30 or higher – swallows the capsule.

After a doctor confirms that it has entered the stomach using X-rays, the balloon is inflated and the tube detached and pulled out.

The filled balloon, which floats atop the gastric fluids, fools the patient into believing that he or she isn’t hungry. “For a few weeks, at least,” Ortíz said. Then a second balloon is inserted, even a third, if needed. After 12-16 weeks, all balloons are removed, at which point the patient has typically “lost 50 percent of his excess weight,” he added.

It’s a protocol that Ortíz himself helped draw up.

Obalon Therapeutics approached him in 2008 to be a consultant for the medical device and to conduct some of the earliest trials of the device.

“He had a long experience and expertise in gastric surgery,” Mark Mahmood, executive vice president for marketing at Obalon Therapeutics in San Diego, Calif, explained to Fox News Latino. “And his facility in Tijuana is world-class.” Certified as an “International Center of Excellence” by the Surgical Review Corporation, in fact.

Obalon follows on other gastric balloons that are filled with saline solution and sit in the bottom of the stomach. There have been no head-to-head studies conducted between the two types of balloon, but early studies conducted by Ortíz and European investigators suggest that Obalon is more easily tolerated than saline-filled balloons, meaning that patients experience less cramping, vomiting and nausea.

Ortiz, who has performed by his estimate 15,000 or so gastric surgeries, believes that Obalon is the most promising weight loss treatment he has seen.

Of course, a lot more studies need to be performed, and it hasn’t been around long enough to know if there are any long-term effects or to be absolutely certain whether it’s advisable if you have other conditions (diabetes, heart disease).

Ortíz and Mahmood both stress that Obalon, like any gastric procedure, won’t help keep weight off unless the patient also undergoes “a change in habit,” as Ortíz put it.

“We used all our experience as surgeons and doctors,” Ortíz said, “to design a smart phone app that tracks what patients eat, how much they exercise and feeds that information into our nutritionist’s database. We can warn patients that they’ve eaten too much grease or haven’t drunk enough liquids. The same day, in real time.”

Ortíz points out that many people trying to change their eating habits slip and then face “a cascade of events – feelings of depression, eating more – that make it so that one visit to our office every two weeks isn’t enough.”

So one “treatment” at Ortíz’s Obesity Control Center costs the equivalent of $3,800—that includes the insertion of two or three balloons, regular follow-ups, nutrition plan, protein shakes and, of course, removal of the balloons.

Obalon has been available in Europe since August 2012, according to Mahmood. In the Americas, the only country where it’s been cleared, since November of last year, is Mexico. (Brazil is fairly close to approving the procedure.)

Ortíz helped train the 20 or so bariatric surgeons who perform the procedure in Mexico, but only a handful of facilities are offering the procedure yet, so the demand for the treatment north of the border is big.

Asked what percentage of his Obalon clientele crossed the border, Ortíz said he couldn’t be sure, but he offered that, “Overall about 98 percent of our patients come from the U.S. or Canada.”

All Mahmood would say about when Obalon might be cleared for use stateside was, “We have conducted two small feasibility studies in the U.S., and we’re working with the FDA on conducting trials.”

Ortíz suggested that based on the pace that other procedures he’s tracked have moved through the approval process, he thinks it might be a matter of a couple of years.

“There’s a misunderstanding about the medical system in Mexico,” he said. “The protocols here are very thorough, but they facilitate a level of research that happens much more slowly in the U.S. Mexico is a great place to do medical research.”