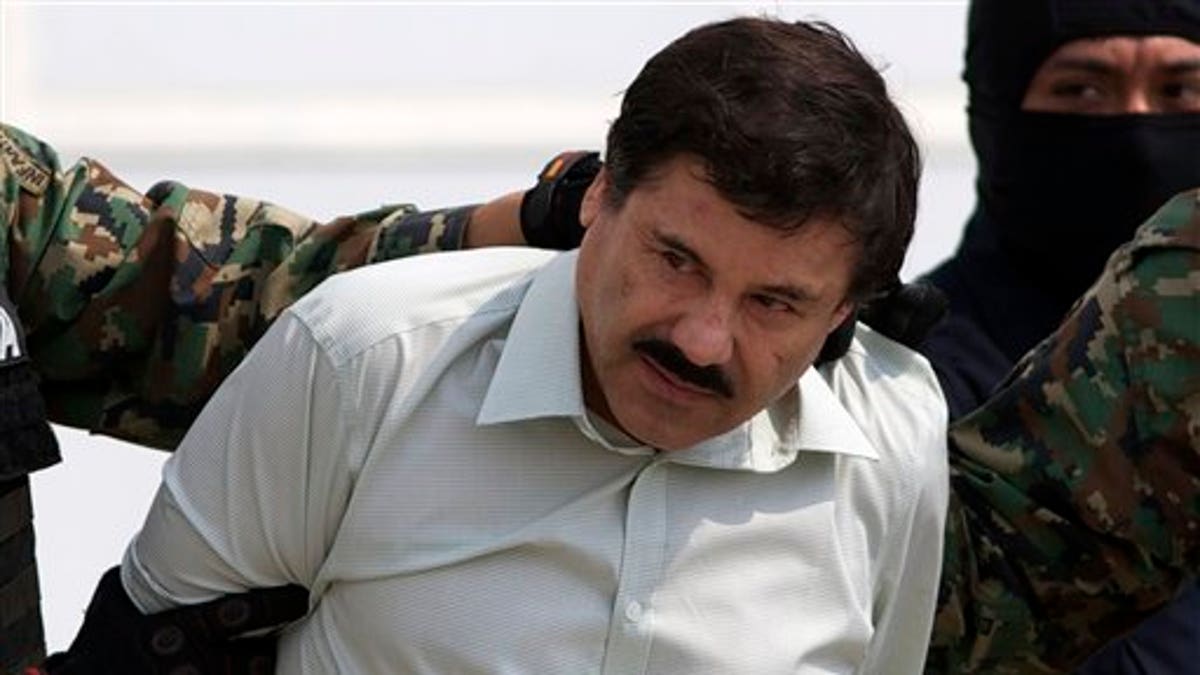

Joaquin "El Chapo" Guzman is escorted to a helicopter in handcuffs by Mexican navy marines at a navy hanger in Mexico City, Saturday, Feb. 22, 2014. A senior U.S. law enforcement official said Saturday, that Guzman, the head of Mexicoís Sinaloa Cartel, was captured alive overnight in the beach resort town of Mazatlan. Guzman faces multiple federal drug trafficking indictments in the U.S. and is on the Drug Enforcement Administrationís most-wanted list. (AP Photo/Eduardo Verdugo)

MEXICO CITY (AP) – Drug kingpin Joaquín "El Chapo" Guzmán has been formally charged with violations of Mexico's drug-trafficking laws, starting a legal process that makes swift extradition to the U.S. unlikely, Mexican officials said Monday.

Guzmán was charged with cocaine trafficking Sunday inside a maximum-security prison outside the nation's capital, Mexico's Federal Judicial Council announced. A judge has until Tuesday to decide whether to release him or start the process of bringing him to trial. Authorities believe the judge will launch the trial process, a Mexican federal official told The Associated Press on condition of anonymity because he was not authorized to publicly discuss the matter.

Guzmán can appeal the judge's decision, a process that typically takes weeks or months, and in the past top drug suspects have often strung out appeals against extradition for months or years.

Mexican officials are also weighing whether to renew a string of other charges that Guzmán faces inside Mexico. The decision to bring one local charge against Guzmán indicates that President Enrique Peña Nieto's administration is leaning toward refiling at least some of the others, further delaying any possible extradition.

Guzmán escaped a Mexican prison in 2001 and spent the next 13 years on the run before he was arrested Saturday morning in the Pacific coast city of Mazatlan by Mexican marines acting on U.S. intelligence. He faces charges in at least seven U.S. jurisdictions and U.S. officials have been pushing for his swift extradition.

It is a politically sensitive subject for the Peña Nieto administration, which has sought to carve out more control over joint anti-drug efforts with the United States. Analysts said the Peña Nieto administration was likely torn between the impulse to move Guzmán to a nearly invulnerable U.S. facility, and the desire to show that Mexico can successful retry and incarcerate the man whose time as the fugitive head of the world's most powerful drug cartel had embarrassed successive Mexican administrations.

Many in Mexico see extradition as the best way to punish Guzmán and break apart his empire, given the United States' more certain legal system and better investigation capacities.

"The only option that would allow for dismantling this criminal network is extradition, and that's unfortunate," said Edgardo Buscaglia, an expert on the cartel and a senior research scholar at Colombia University. "Because, in the end, extraditions are an escape valve for Mexico," which has been slow to improve its own investigative police, prosecution and court system.

"There are arguments for and against extraditing him," said security expert Jorge Chabat. "If he stays in Mexico there are risks he could escape or continue to control his criminal organization from inside prison," said Chabat, while noting that Peña Nieto's Institutional Revolutionary Party "has been loath to extradite criminals for nationalistic reasons ... I think it a decision the Mexican government is weighing right now."

Guzmán and his Sinaloa cartel allies have hundreds of millions, perhaps billions, of dollars at their disposal, along with networks of corrupt officials, hitmen and other allies throughout Mexico. The cartel is believed to sell cocaine, marijuana, heroin and methamphetamine in about 54 countries.

The Federal Judicial Council said the cocaine-trafficking charges date to 2009. The federal official said the Mexican government is weighing whether to try to send Guzmán back to prison on the convictions for criminal association and bribery that he was serving time for when he escaped. At the time of his flight, he was also awaiting trial on charges of murder and drug trafficking, and the official said the Mexican government was also weighing whether to refile those charges.

Guzmán was captured just after sunrise Saturday hiding out in a condominium in Mazatlan, a resort town on Mexico's Pacific Coast.

He had a military-style assault rifle with him but didn't fire a shot, according to officials with knowledge of his arrest. His beauty-queen wife, Emma Coronel, was with him when the manhunt for one of the world's most wanted drug traffickers ended.

The officials spoke on the condition of anonymity because they were not authorized to discuss specific details of how U.S. authorities tracked down Guzmán.

The break that led to his arrest came on Feb. 16, when investigators from Mexico along with the Drug Enforcement Administration, the U.S. Marshals Service and Immigration and Customs Enforcement tracked a cellphone to one of the Culiacan stash houses Guzmán used to elude capture.

The phone was connected to his communications chief, Carlos Manuel Ramírez, whose nickname is Condor. By the next day, Mexican authorities arrested one of Guzmán's top couriers, who promptly provided details of the stash houses Guzmán and his associates had been using, the officials said.

At each house, the Mexican military found the same thing: steel reinforced doors and an escape hatch below a bathtub. Each hatch led to a series of interconnected tunnels in the city's drainage system.

The officials said three tons of drugs, suspected to be cocaine and methamphetamine, were found at one stash house.

An AP reporter who walked through one tunnel had to dismount into a canal and stoop to enter the drain pipe, which was filled with water and mud and smelled of sewage. About 700 meters (yards) in, a trap door was open, revealing a newly constructed tunnel. Large and lined with wood panels like a cabin, the passage had lighting and air conditioning. At the end of the tunnel was a blue ladder attached to the wall that led to one of the houses Mexican authorities say Guzmán used as a hideout.

A day after troops narrowly missed Guzmán in Culiacán, top aide Manuel López Ozorio was arrested. The officials said he told investigators that he picked up Guzmán, Ramírez and a woman from a drainage pipe and helped them flee to Mazatlán.

A wiretap being monitored by ICE agents in southern Arizona provided the final clue, helping track Guzmán to the beachfront condo, the officials said.

The ICE wiretap proved the most crucial lead late last week as other wiretaps became useless as Guzmán and his associates reacted to coming so close to being caught.

"It just all came together and we got the right people to flip and we were up on good wire," the government official said. "The ICE wire was the last one standing. That wire in Nogales. That got him (Guzmán) inside that (building)."

Alonzo Peña, a former senior official at ICE, said wiretaps in Arizona led authorities to the Culiacán house of Guzmán's ex-wife, Griselda López, and to the Mazatlán condominium where Guzmán was arrested.

The ICE investigation started about a year ago with a tip from the agency's Atlanta office that someone was crossing the border with about $100,000 at a time, said Peña, who was briefed on the investigation. That person led investigators to another cartel operative, believed to be an aircraft broker, and that allowed them to locate Guzmán's communications equipment.

The senior law enforcement official said the Mexican marines deserve credit for taking Guzmán alive and without either side firing a shot.

"We never anticipated, ever, that he would be taken alive," the official said.

Grand juries in at least seven U.S. federal district courts, including Chicago, San Diego, New York and Texas, have already issued indictments for Guzmán on a variety of charges, ranging from smuggling cocaine and heroin to participating in an ongoing criminal enterprise involving murder and racketeering.

Federal officials in Chicago were among the first to say they wanted to try Guzmán. On Sunday, Assistant U.S. Attorney Steven Tiscione in Brooklyn became the second. In an email Sunday, Tiscione said his office would also be seeking extradition but it would be up to Washington to make the final call.

Follow us on twitter.com/foxnewslatino

Like us at facebook.com/foxnewslatino