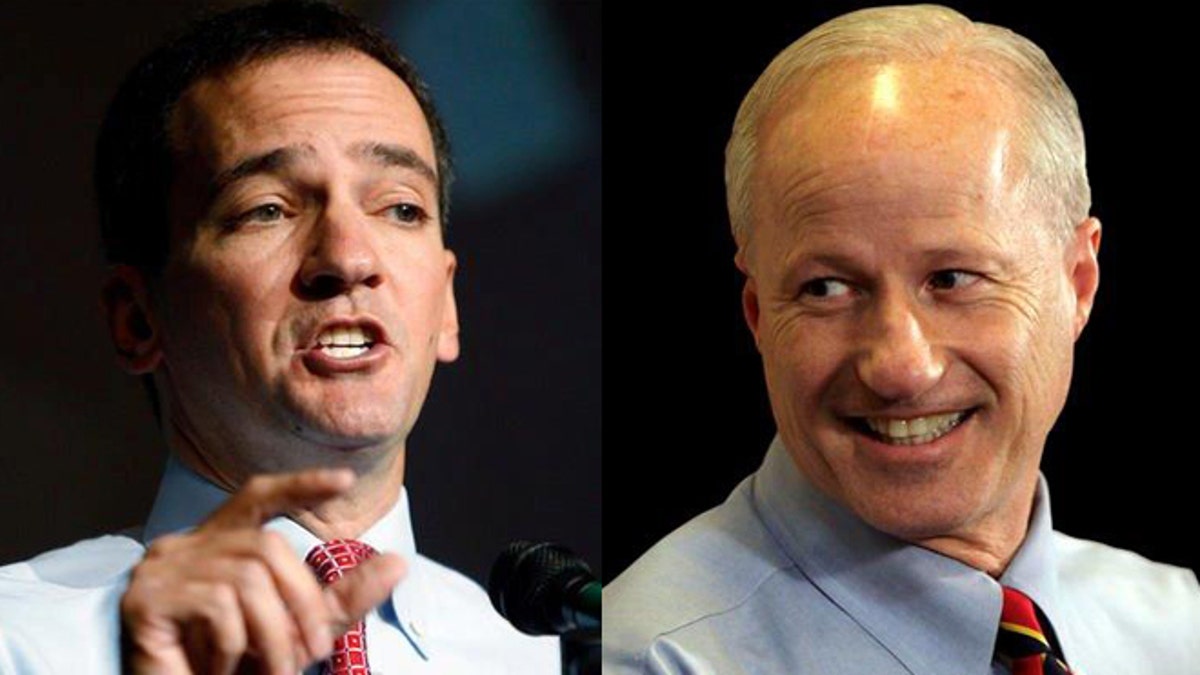

Andrew Romanoff (left) and Mike Coffman (right) face off in a televised Spanish-language debate on Thursday, Oct. 30, 2014. (Photos: AP)

On Thursday, Colorado – one of the most closely watched states this midterm election season – will have its first all-Spanish congressional debate.

U.S. Rep. Mike Coffman, a Republican, and his Democratic challenger, Andrew Romanoff, will be fielding questions and answering them in Spanish in a televised debate on the local Univision station.

Latinos are hailing the event, saying it serves as testimony to the importance of their community, which many political observers say can play in pivotal role in the hotly-contested contest.

“It absolutely demonstrates just how crucial the Latino vote will be in this race,” said Julie Gonzales, the statewide co-chair of the Colorado Latino Forum. “Latinos can represent the margin of victory in the 6th congressional district and other districts, too.”

Romanoff, a former speaker of the state House of Representatives and the loser of a 2010 bid for the U.S. Senate, is fluent in Spanish, while Coffman has been studying the language with a tutor.

This is the first time in Colorado that congressional candidates have held a Spanish-language debate, and it is a rare event on a national level, as well. The debate will not have English-language subtitles, but there will be an interpreter on hand for English-language media in attendance.

To be sure, candidates running for office at different levels of government around the United States increasingly have been participating in debates targeting Spanish-speakers, but usually only one, sometimes neither, of the candidates is fluent and translators usually are employed.

Political experts say the result of this trend is a more educated immigrant electorate.

“The more information you have in either language, the more of an informed electorate you’re going to have,” said Jose Dante Parra, a Democratic strategist who headed Latino communications for U.S. Sen. Harry Reid, a Nevada Democrat, in 2010. “The more information voters can get, the more we can expand opportunities for voters to cast their ballot and exercise their constitutional right.”

The Latino community in Colorado is among the state’s fastest-growing.

The challenge for political candidates, Parra said, is that the electorate consists of Latinos born in the United States, or bred here, and immigrants who are naturalized citizens and are eager to get involved and vote, but are not yet fluent in English.

“My parents, for example, came here when they were older,” Parra said. “Both of them did night school as much as they could to learn English, but my dad had to take an extra job. My dad is more likely to get his information in Spanish than in English.”

For immigrants like his father, Parra said, a Spanish-language debate – especially one without the middle layers of translators and subtitles – gives voters a rare opportunity “to get information beyond the campaign commercials.”

The idea for a debate in Spanish only has been kicked around for a long time, those involved say.

“We’ve been talking about a debate for many many years,” said Don Daboub, senior vice president at Entravision Communications Colorado, an Univision affiliate. “We felt it was the best forum to have both parties relay their values and what’s important to them.”

Daboub said that debates targeting Spanish-speakers marks the “beginning of a new, necessary [step] for our community and growing Hispanic voters in the country."

Ben Monterroso, the executive director of Mi Familia Vota, which has been working to register Latinos nationwide to vote, said the debate shows that Latinos in Colorado have come a long way.

He noted that the congressional district that is holding the Spanish-language debate is also the one that had one of the country’s most polarizing recent representatives to Latinos – Tom Tancredo, a Republican who served in the House from 1999 to 2009.

Tancredo drew the ire of many because of his hard line on undocumented immigrants, as well as the matching rhetoric he was prone to.

“It’s testament to the work that the Latino community has been doing to participate in the civic life of this country,” Monterroso said. “In the district that used to be represented by an anti-immigrant [like] Tom Tancredo, this acknowledges that the community is part of this country, and it's [the political establishment] understanding that if you want democracy, you cannot ignore this population.”

Coffman is viewed with skepticism by many Latinos.

The Republican, whose district was redrawn in 2011 and now is about one-fifth Latino, at one time aggressively pushed for hard-line immigration measures and introduced a measure to stop ballots from being available in languages other than English.

“Coffman has been doing Latino outreach,” Gonzales said, “but he has a reputation for saying one thing to Latinos and then doing another. It has really raised a lot of questions about him.”

Like Coffman, Romanoff has drawn the ire of Latino activists in the past.

When Congress failed to pass immigration reform several years ago, Colorado, like various other states across the country, moved forward with efforts to pass its own state measures to crack down on undocumented immigrants.

Romanoff, who was speaker of the state House until 2008, backed them.

“Those measures were draconian and far-reaching,” Gonzales said.

The difference, she added, is that Romanoff has gone out of his way since to try to mend relations with Latinos in the state, and now says that states should not deal with immigration matters.

“We want someone representing us in Congress who will push for immigration reform on a daily basis,” she said. “He’s done an incredible amount of outreach to talk about the need for comprehensive immigration reform and better education for Latinos.”

Coffman has been less accessible, she said.

“We’ve tried for months to meet meaningfully with the congressman, we even went so far as to have a sit-in in his office to try to get a meeting,” Gonzales said. “He hasn't really been willing to sit down and have conversations with Latino communities about his record.”

Alfonso Aguilar, executive director of the American Principles Project’s Latino Partnership, which targets Latino conservatives, said that Hispanics do give candidates credit for making an effort to address them in Spanish, whether directly or indirectly.

“The Latino community appreciates when candidates are willing to go on Spanish-language TV, even if it’s with a voiceover or translator,” said Aguilar, who worked for the George W. Bush administration. This year, he pointed out, "we saw debates for Spanish-language voters in New Mexico, in Florida – Gov. Rick Scott said a few things in Spanish at the end of the debate. It shows there’s a recognition that the Latino vote matters.”

Gonzales agrees. “That both candidates for whom Spanish is a second language are reaching out and really making an effort, stretching out of their comfort zone,” she said, “hopefully will demonstrate to other candidates across the state and other places that stretching and doing something that may not be comfortable, and reaching out to all your constituents, can go a long way.”