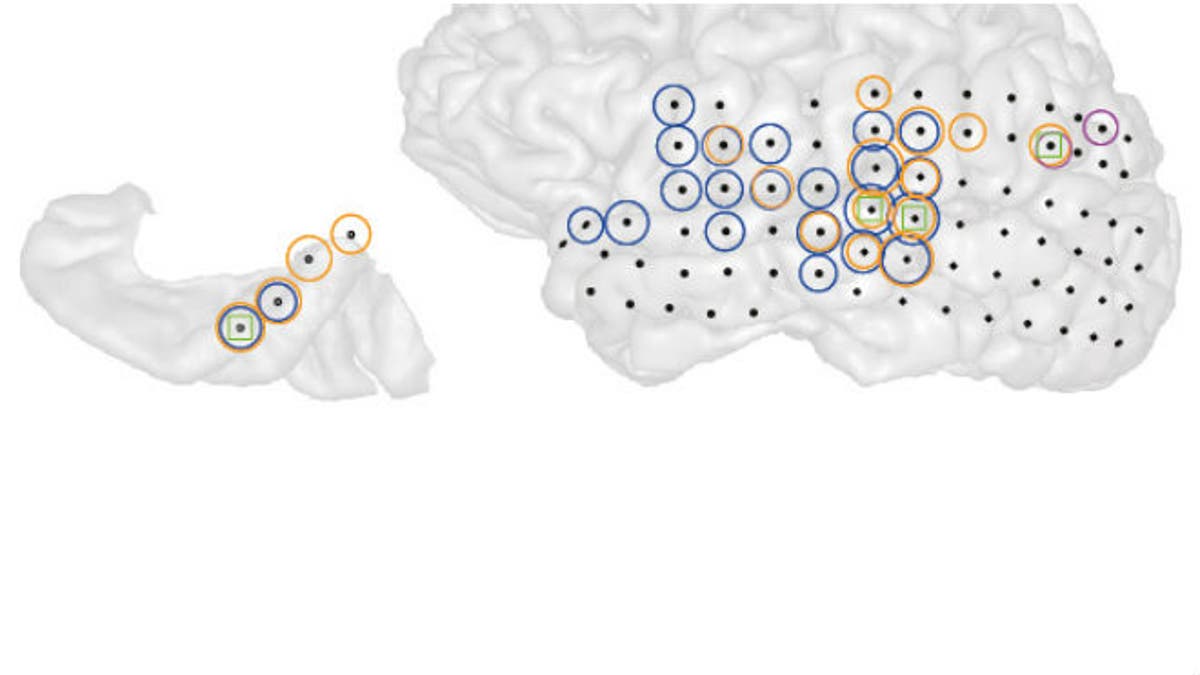

This is a 3-D image of the left brain hemisphere of a patient with tinnitus (right) and the part of that hemisphere containing primary auditory cortex (left). Black dots indicate all the sites recorded from. Colored circles indicate electrodes at which the strength of ongoing brain activity correlated with the current strength of tinnitus perceived by the patient. Different colors indicate different frequencies of brain activity (blue = low, magenta = middle, orange = high) whose strength changed alongside tinnitus. Green squares indicate sites where the interaction between these different frequencies changed alongside changes in tinnitus. (Image: Sedley, W et al.)

Tinnitus, a noise or ringing in the head or ear, affects an extensive network of the brain— not just its auditory region— a finding that may allow for more effective treatments in the future, reveals a study published Thursday in Current Biology.

Researchers Phillip Gander, of University of Iowa, and William Sedley, of Newcastle University in the U.K., had the rare opportunity to record directly from the brain of a person with tinnitus to find the brain networks responsible for the condition, in which there is the perception of sound in the absence of an external source.

While most people experience intermittent tinnitus at some point, and hearing loss with age is normal, chronic tinnitus affects about 10 to 15 percent of the population. According to the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs’ 2013 data, tinnitus is also the No. 1 service-related compensation for veterans. The most prevalent disability among this group, the condition affects about 1,121,710 veterans.

The causes of tinnitus are variable, acquired throughout a person’s lifetime, and typically result from noise trauma.

“This is a big deal because tinnitus currently has no cure and no real effective treatment, probably in large part because it’s so variable in terms of, across different people that they experience it differently and across different people they react differently,” Gander told FoxNews.com.

Finding a proper participant for their study was serendipitous, researchers noted. In this case, the 50-year-old male subject had bilateral tinnitus affecting both ears, he heard a single, high-frequency tone— rather than a rushing, white noise— and he already had hearing loss.

“If we were to generalize across the population of people studied, this seems to be more typical,” Gander said.

To study the subject’s tinnitus-linked brain activity, researchers tried to temporarily suppress the chronic sound by playing a loud noise for 30 seconds. After turning off the external noise, tinnitus can get quieter or go away for a brief period of time. Researchers then looked at brain scans of when the subject’s tinnitus went away and compared them to times when he experienced no change.

Researchers said they were fortunate because the same noise seemed to randomly make his tinnitus get quieter half the time, and didn’t for the other half— making the man his own control subject.

“That’s why our experiment was really powerful: because it controls for all those other factors related to tinnitus— attention, fatigue— across different experiment conditions. If [the subject] was tired, he was tired across both conditions,” said Gander, who noted that this characteristic prevented confounding factors from impacting the study results.

By directly recording brain activity, researchers were able to conclude that tinnitus affects a large expanse of the brain— not just the sound areas— including regions related to emotions, memory and mood.

“What we’re hoping is that the details of the brain networks and brain mechanisms we highlight in our paper can be starting points that people could target [for treatment],” Gander said.

One of the most effective treatments for individuals with tinnitus-induced distress is psychological treatment, Gander said. Cognitive behavioral therapy helps people cope with how to think about and how to ignore their tinnitus— not with changing or getting rid of the sound. However, there is no cure for tinnitus.

Past theories hypothesized that tinnitus only affected the auditory part of the brain and perhaps regions of hearing loss, but this new research shows that tinnitus processes in the brain differently from the way we normally hear or process sound. This explains why current treatments aren’t effective, Gander said.

“Our study definitely highlights why so many treatments have been ineffective so far because we’re trying to target one of these brain regions, but what seems to be the case is that it actually is going to need to involve a bunch of areas at the same time,” Gander said. “If that’s right, [treatment] will be very difficult, very complicated.”

The man was a patient of the University of Iowa’s Iowa Comprehensive Epilepsy Program (ICEP), which offers surgical treatment for its most serious patients. That surgery involves removing the part of the brain that causes epileptic seizures. To remove the minimal amount of brain tissue, doctors implant electrodes in and on the surface of the brain to record where seizures are generated. The patients must wait at the hospital until their next seizure, so in the meantime, scientists from the university may recruit them to voluntarily help out with other research.

“It is such a rarity that a person requiring invasive electrode monitoring for epilepsy also has tinnitus that we aim to study every such person if they are willing,” Gander said.