New fertility treatment for PCOS patients

See how a new fertility procedure is helping women with polycystic ovarian syndrome get pregnant without all the hormone injections, and for a fraction of the cost of traditional IVF

For millions of women suffering from polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS), trying to conceive can be a heart-breaking experience. But a new procedure is making it easier for patients to get pregnant without hormone injections, meaning a decreased risk for certain complications.

“PCOS is an endocrine disorder where women don’t ovulate on a regular basis,” Dr. Jesse Hade, medical director at Neway Fertility in New York City told FoxNews.com. “It's usually characterized by having multiple little follicles in the ovaries that appear on ultrasound, or having irregular periods, coupled with elevated male hormone levels, or elevated androgen levels.”

Manpreet Sangari, 32, was diagnosed with PCOS after months of trying to get pregnant proved unsuccessful.

“Basically it will be very hard for me to ovulate on my own and have kids … It would be, not a miracle, but it would just, it would take a long time, and that's when [my obstetrician] told me I should go to a fertility doctor,” Sangari told FoxNews.com. “And hearing all that was just crazy because now you're adding more people into the process of baby making, which should have been so simple.”

Sangari went to see Hade, who suggested she try a less-invasive procedure like intrauterine insemination (IUI) before jumping into in vitro fertilization (IVF). But the IUI procedure did not produce a pregnancy, so Sangari tried a round of IVF.

The procedure was a success and Sangari and her husband, 36-year-old Sarbdeep Mokha, were overjoyed to learn she was pregnant with twins. But their excitement was short lived when, not long after, the unthinkable happened.

“I ended up [having a] preterm delivery on the 23rd week and the babies didn't survive,” said Sangari. “The procedure itself was successful, the IVF was successful -- the carrying of the babies was not successful.”

Three months later, when Sangari was ready to try again, Hade suggested a different kind of fertility treatment called in vitro maturation (IVM).

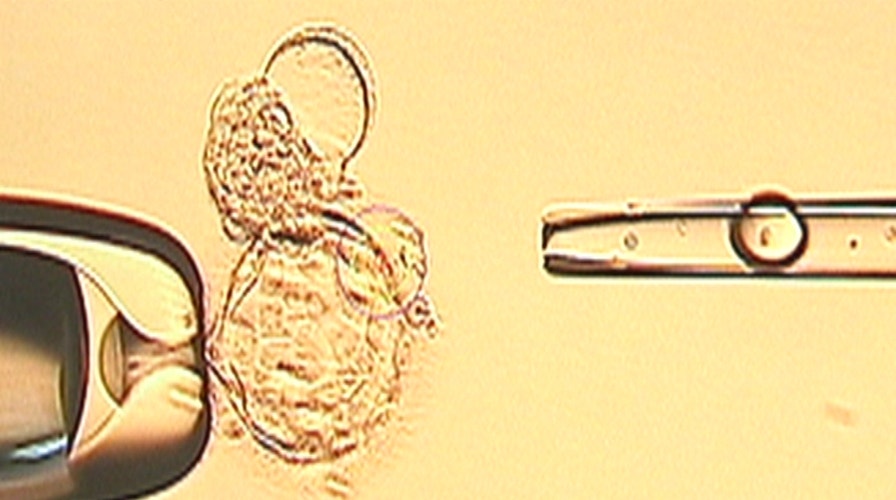

“Usually women with … PCOS are the primary candidates for this procedure because they have lots of little immature follicles which lead to lots of little immature eggs. We then go ahead and harvest all these immature eggs, remove them, and then mature them in the petri dish,” Hade said.

With traditional IVF, patients typically inject themselves with hormone medications for eight to 10 days to stimulate the ovaries into producing multiple eggs for fertilization. This increases the chances of creating healthy embryos for transfer into the uterus.

But hormone injections can be dangerous for PCOS patients because they have an increased risk for ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome (OHSS) – a condition that causes the ovaries to become swollen and painful. Sangari developed OHSS during her IVF trial, making her the perfect candidate for IVM.

“In in-vitro maturation, little to none of these [hormone] drugs are given initially, so what we're doing is preparing the endometrium for implantation with hormones to … prime the lining,” Hade said. “And in this process, we wait until the endometrial receptivity gets to its best point, and that's when we trigger the ovulation and remove the immature eggs out.”

The treatment is still considered experimental, so it’s not covered by insurance. But Hade hopes to change that with an ongoing IVM study he is conducting that has shown success rates of 80 percent so far.

Sangari had the procedure, and in October 2013 she and her husband welcomed a daughter, Zoya. They plan on trying for another child.

“We're hoping Dr. Hade helps us get the second baby,” said Sangari. “We had thought of having two kids, and after the first time we got one back, and we need one more.”

For more information or to enroll in the study, visit Dr. Hade’s website NewayFertility.com.