Dr. Nicole Saphier on combatting the second wave of coronavirus

Our technology has advanced, our diagnostics have improved and our testing capability has advanced since the beginning of this pandemic, says Dr. Nicole Saphier, Fox News medical contributor.

Researchers are nearing completion of a mathematical algorithm to help pinpoint the source of coronavirus infections within sewer systems.

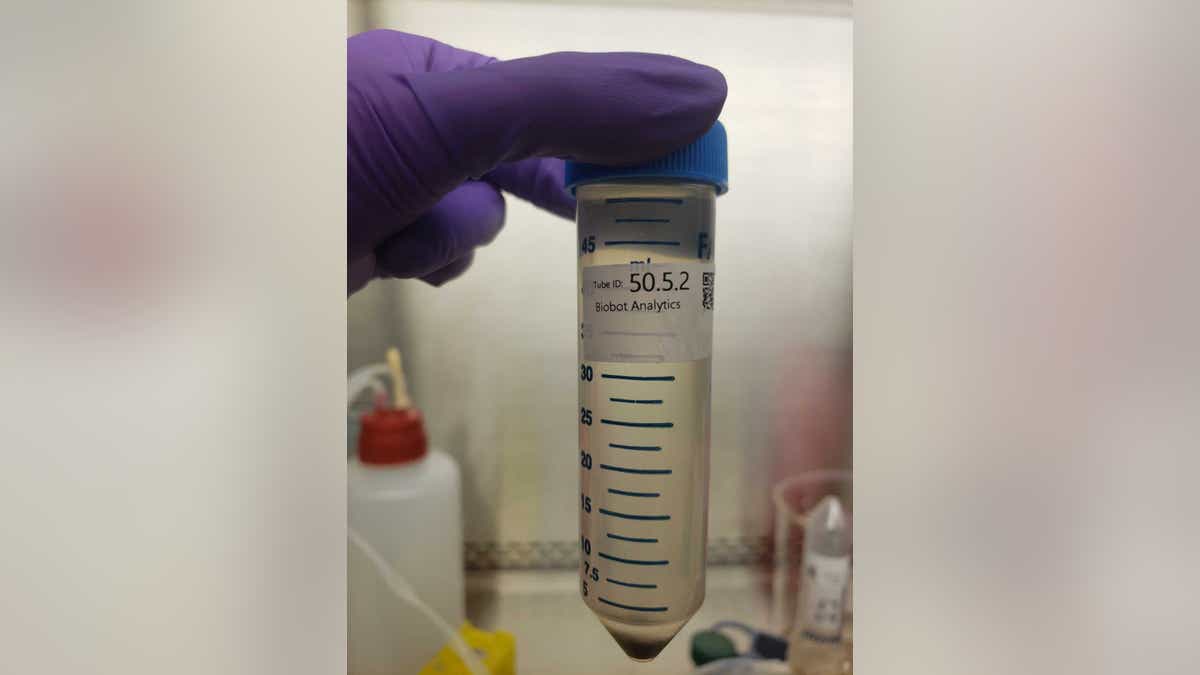

Reports arose earlier in the pandemic of universities and cities looking to sewage for traces of the virus, to more quickly identify and isolate virus cases; each flush from an infected person sends genetic remnants of the virus into sewage systems. A company called Biobot, for instance, has worked with about 400 facilities in 42 states to map virus concentrations in sewage over time, with current data representing over 10% of the U.S. population, a spokesperson told Fox News.

Biobot has been working to map virus concentrations in sewage over time. (Courtesy of Biobot)

Now, Richard Larson, professor at MIT Institute for Data, Systems and Society, says his team, which includes researchers in Toronto, expects to publish a paper in the coming weeks on a new algorithm to narrow the hunt in a given sewage system for the source of infection.

Richard Larson, professor at MIT Institute for Data System and Society, says his team expects to publish a paper in the coming weeks on a new algorithm (Photo courtesy Richard Larson)

CLICK HERE FOR FULL CORONAVIRUS COVERAGE

“We’ve developed a way to sequentially sample a small number of manholes in the sewer system of a town or city,” Larson told Fox News. While a typical town might have hundreds of manholes, the algorithm eliminates suspected manholes down to about 10 of interest “exponentially quickly,” he explained.

This process of “honing in” may save considerable time and effort in contact tracing investigations. In fact, just on Wednesday, the Philadelphia Inquirer reported that an estimated 15% to 20% of people in the city who have tested positive will not be contacted by tracers, per Hannah Lawman, chief of operations for the city’s Division of COVID Containment.

RAPID CORONAVIRUS SPREAD IN THIS CITY LEAVES CONTACT TRACERS UNABLE TO TRACK ALL CASES

There are two algorithms, Larson says: the first assumes a "pristine" community with no infections, and then one or two crop up in a household. In this scenario, the team would begin the search halfway up the network of sewer lines, uncover the manhole and take a sample. If it comes back positive, Larson says it signals the infected person is located “upstream,” and so the search continues. All of the manholes located downstream would be put aside because they’re no longer of interest.

Reports arose earlier in the pandemic of universities and cities looking to sewage for traces of the virus. Here, Biobot tests a sewage sample for genetic remnants of the virus. (Courtesy of Biobot)

The end of the process would land the team on the block of where the infected person lives, at which point all of those living on the block would be tested.

However, a second algorithm accounts for multiple infections cropping up across a town or city. The method uses the same logic as previously mentioned, but instead of winding up on the infected individuals' block, the search would point to a hotspot involving numerous households, where Larson theorized public messaging on mask use and hygienic behavior could be practical to reduce virus spread.

However, Larson forewarned that his team does not consist of civil engineers or experts in the plumbing of these systems. Also, the algorithm likely would not work in century-old, decrepit sewage systems because they tend to leak and co-mingle with storm sewage, he said. Also, larger systems with more wastewater plants could complicate the process, but Larson says, for example, across the five boroughs in New York City, the algorithm would be run five times.

The team also awaits the development of a fast, inexpensive on-site test for sewage fluid, with companies reportedly telling researchers a five-minute test could come about within a month or two.

Larson expects considerable in-field testing work in 2021, accounting for the makeup and creation date of pipes, and how well application would pan out.

Finally, this forthcoming algorithm is intended to complement ongoing virus testing, and is not meant to serve as a substitute. Larson says this mechanism could help toggle between normal testing to an emergency schedule to locate asymptomatic cases fast before they infect others.

CLICK HERE FOR THE FOX NEWS APP

Fox News' Madeline Farber contributed to this report.