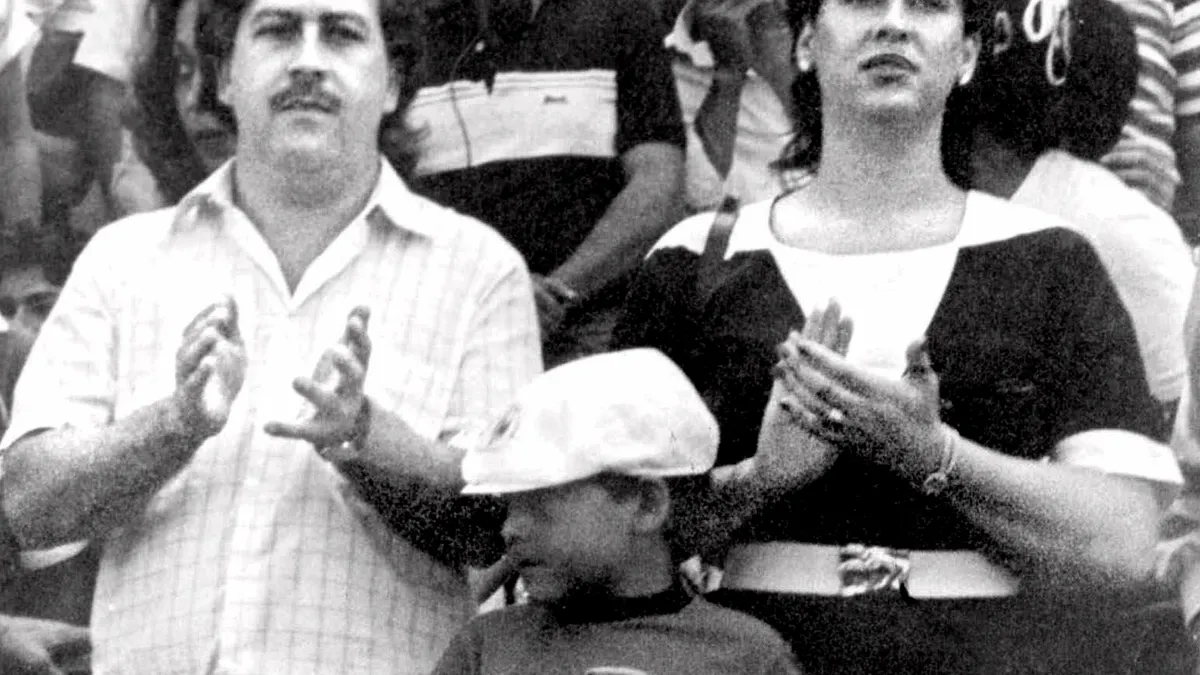

FILE - In this undated file photo, the late Pablo Escobar, former boss of the Medellin drug cartel, his wife Maria Henao and their son Juan Pablo, attend a soccer match in Bogota, Colombia. The widow of Pablo Escobar fell madly in love as a preteen with the man who would rise to be a ruthless drug lord, but says in a new book she felt raped when at age 14 he forced her to have an abortion, and over time came to view him as a cruel psychopath. (El Tiempo Photo via AP File)

BOGOTA, Colombia – The widow of Pablo Escobar fell madly in love as a preteen with the man who would rise to be a ruthless drug lord, but she says she felt raped when at age 14 he forced her to have a clandestine abortion, and over time came to view him as a cruel psychopath.

The revelation comes in a memoir, "My Life and My Prison With Pablo Escobar," in which Maria Henao for the first time opens up about her life alongside one of the world's most ruthless criminals, portraying herself more as a victim of the boundless violence of the Medellin cartel boss than as an accomplice to his lawbreaking.

In the book's epilogue, titled "The secret I've held for years," Henao describes being taken by Escobar to a ramshackle clinic and lying down on a stretcher while an elderly woman inserted several plastic tubes into her womb. She says she didn't know she was pregnant and was told it was just a means of pregnancy prevention. Over several days she endured bleeding and intense pain as a pregnancy was aborted. With time, and much therapy, she says she came to view the experience as a "violation."

She writes that she had been "paralyzed" with fear the first time Escobar was intimate with her. "I wasn't ready, I did not feel sexual malice, I did not have the necessary tools to understand what this intimate and intense contact meant," she says.

Talking of the abortion, something she had kept even from her children until now, she says, "I had to connect with my history and immerse myself in the depths of my soul, to find the courage to reveal the sad secret that I have harbored for 44 years."

Henao says she decided to break her long silence and write the 523-page book with the hope that younger generations of Colombians would see how much blood has spilled in Colombia as a result of its cocaine business.

But it is also a page-turner that provides an intimate look at Escobar's fast evolution from a small-time grave robber to one of the world's most wanted fugitives.

Henao says she met Escobar when she was 12. She came from an upstanding, traditional family in the Envigado district near Medellin and disobeyed her parents by falling in love with Escobar, the son of a poor watchman who rode around their neighborhood in a flashy Vespa motorcycle and was 11 years her senior.

During a courtship that led to marriage when Henao was 15, Escobar showered her with gifts like a yellow bicycle and serenades of romantic ballads.

"He made me feel like a fairy princess and I was convinced he was my Prince Charming," she writes.

But from the start there were long, unexplained absences and he frequently flirted with other women. As Escobar began to amass a fortune, he also became manipulative and paranoid, she says.

Henao insists she was largely kept in the dark about details of his criminal activities and says she escaped from the "inferno" of living alongside Escobar by creating an alternative world devoted to their two children and collecting expensive artworks by the likes of Dali and Rodin.

After the Medellin cartel's 1984 assassination of Justice Minister Rodrigo Lara, Escobar went into hiding and waged a bloody war with the state that included killing a presidential candidate and blowing up a commercial jetliner. Over much of the next decade, until Escobar died during a 1993 rooftop shootout with police, the family's contact with the kingpin consisted of short visits to safe houses where Henao and her children arrived blindfolded and were escorted by Escobar's army of assassins.

In an interview Wednesday with Colombia's W Radio before the Nov. 15 publication of the book, Henao started off by apologizing to Colombians for what she said was the enormous damage her husband caused the nation. Referring to him throughout the interview as "Pablo Escobar," she said she felt a mix of pain, profound embarrassment and disappointment with the man who had been the love of her life.

"I chose to bear all of this pain to protect my children," she said.

After Escobar was killed, Henao began a frenzied search for asylum, fearing that his many enemies would extract revenge and kill her children. After being turned down by Germany and Mozambique, among other countries, they settled in Buenos Aires, Argentina, and changed their names.

There, an attempt to lead a relatively normal life was interrupted when they were arrested in 1999 for money laundering. They were charged again this year for allegedly helping a Colombian drug trafficker hide money through real estate and a cafe known for its tango performances. Henao denies any wrongdoing and said once again that she and her children are being unfairly targeted because of their former last name.

In 2009, Escobar's son, who now goes by the name Sebastian Marroquin, starred in a documentary in which he seeks to atone for his father's sins by meeting with the orphaned sons of Lara and another prominent victim of his father's cartel. The film left Colombians transfixed and spurred a more dispassionate look at Escobar's role in the 1980s and 1990s drug wars.

But with the proliferation of books, the hit Netflix "Narcos" series, and tours of Escobar's former haunts in Medellin, some worry that the capo is being glorified by younger Colombians who didn't live through the bloodbath.

And even a quarter century after his death, not everyone is willing to forgive.

Writing recently in the newspaper El Tiempo, popular columnist Maria Isabel Rueda said that Henao's book "isn't the excuse of a victim, but of a shameless senora who knew perfectly well that she and her family swam in rivers of gold preceded by a flood of deaths."

___

Joshua Goodman on Twitter: https://twitter.com/apjoshgoodman