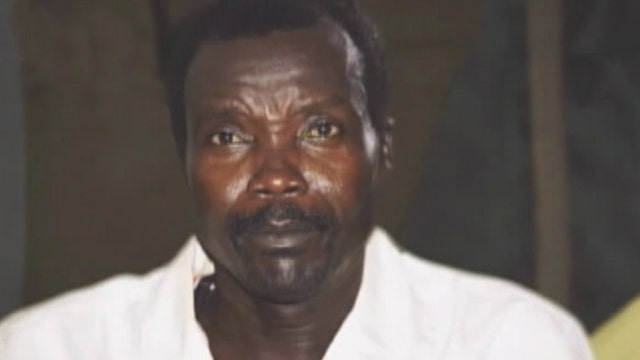

Filmmaker plans mission to track down Joseph Kony

Warlord is 'worth hunting down and bringing to justice'

THE HAGUE, Netherlands – Fugitive warlord Joseph Kony's feared militia deliberately targeted civilians in its conflict with Ugandan government forces, murdering indiscriminately, abducting children to turn into killers "steeped in blood," forcing girls and women into "marriages" with fighters and even ordering cannibalism, an International Criminal Court prosecutor said Thursday.

Prosecution lawyer Ben Gumpert spoke at the start of a hearing to establish whether evidence against Dominic Ongwen, one of the most senior commanders in Kony's Lord's Resistance Army, is strong enough to merit putting him on trial.

Ongwen, first indicted in 2005 and sent to the court a year ago after surrendering to U.S. forces in Central African Republic, is the only member of Kony's murderous army in the court's custody. Kony remains free despite years of efforts in Northern Uganda and neighboring countries to track down and capture him.

Ongwen faces 70 charges including murder, rape, torture, forced marriage and using child soldiers stemming from his alleged involvement in attacks on refugee camps in Uganda in 2003 and 2004.

Originating in Uganda in the 1980s as a tribal uprising against the government, the LRA's rebellion is one of Africa's longest and most brutal. At the peak of its powers the group razed villages, raped women and amputated limbs. It is especially notorious for recruiting boys to fight and taking girls as sex slaves.

Gumpert said Ongwen "bears significant criminal responsibility" for the attacks, during which civilians were killed and tortured, and women and children were abducted.

"Nursing mothers whose babies slowed up the progress or who simply cried too loudly saw them killed or thrown into the bush and left behind," Gumpert said.

He added that Ongwen played a crucial role in transforming abducted children into soldiers, whom Kony saw as "most easily molded into the ruthless killers he needed."

They were forced to perform "individual acts of torture and murder designed to convince recently abducted children that they were so steeped in blood that there could be no acceptance for them back in civilian society," Gumpert said.

As a brigade commander, Ongwen even told abductees "on at least one occasion, to kill, cook and eat civilians," Gumpert said.

Ongwen will have to enter pleas to the charges only if he is ordered to stand trial.

When asked by Presiding Judge Cuno Tarfusser if he wanted the charges read out in court, Ongwen bowed to the three-judge panel and said in his Acholi language that it would be a waste of time.

"You may speak five words and only two are true," he said.

Hundreds of Ugandans watched broadcasts of proceedings in The Hague in different parts of north and northeastern Uganda as part of the court's efforts to reach out to Ongwen's alleged victims.

Betty Amongi, a Ugandan lawmaker who met with Ongwen during failed peace talks in 2005, said she hoped his prosecution will serve as a deterrent.

"This is going to be a landmark case," she said. "If the trial is successful, it will be a good deterrent for the rest of those who think that you can wage war, you can torture people and get away with it."

Gumpert acknowledged that Ongwen himself was a victim of the LRA, having been abducted and forced into its ranks as a 14-year-old.

While Ongwen's personal history could allow judges to consider reducing his sentence if he is tried and convicted, it "cannot begin to amount to a defense, a reason not to hold him to account," Gumpert said.