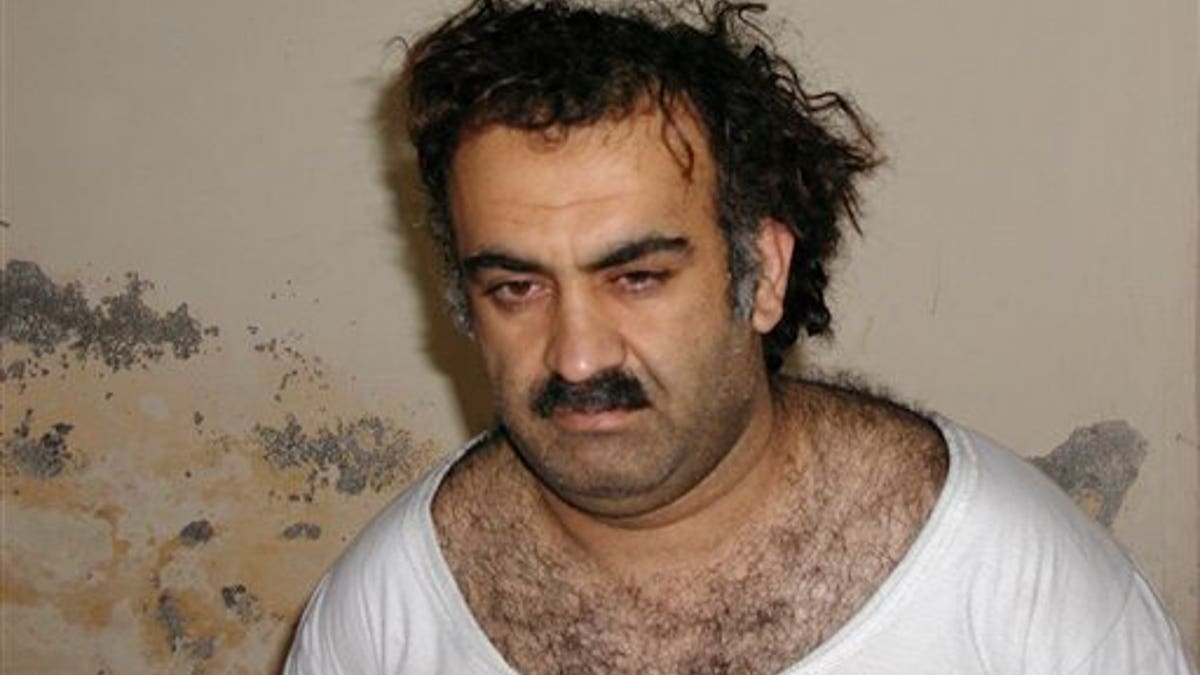

March 2003: Khalid Sheikh Mohammed is seen shortly after his capture during a raid in Pakistan. (AP)

WASHINGTON -- President Obama's decision to resume military trials for detainees at Guantanamo Bay, Cuba, will open the door for the prosecution there of several suspected 9/11 conspirators, including alleged mastermind Khalid Sheikh Mohammed.

Obama's order, which reverses his move two years ago to halt new trials, has reignited arguments over the legality of the military commissions, despite ongoing U.S. efforts to reform the hotly debated system.

But fierce congressional opposition to trying Mohammed and other Guantanamo detainees in the United States left Obama with few options. And it forced him to reluctantly retreat, at least for now, from his promise to shut he prison down.

A handful of detainees have been charged in connection with the Sept. 11, 2001, attacks on America, including Mohammed. But the charges were dismissed following Obama's decision to halt military commissions in January 2009.

Administration officials declined Monday to discuss the potential prosecution of Mohammed or the other detainees. But Senate Republican leader Mitch McConnell said Guantanamo is a safe location for such a trial.

Guantanamo has been a major political and national security headache for the president since he took office promising to close the prison within a year, a deadline that came and went without Obama setting a new one.

The president and his top defense leaders all emphasized their preference for trials in federal civilian courts, and his administration blamed congressional meddling for closing off that avenue.

"I strongly believe that the American system of justice is a key part of our arsenal in the war against al-Qaida and its affiliates, and we will continue to draw on all aspects of our justice system -- including (federal) courts -- to ensure that our security and our values are strengthened," Obama said in a statement.

The first Guantanamo trial likely to proceed under Obama's new order would involve Abd al-Rahim al-Nashiri, the alleged mastermind of the 2000 bombing of the USS Cole. Al-Nashiri, a Saudi of Yemeni descent, has been imprisoned at Guantanamo since 2006.

Defense officials have said that of around 170 detainees at Guantanamo, about 80 are expected to face trial by military commission.

On Monday, the White House reiterated its commitment to eventually close Guantanamo -- which is on a U.S. Navy base on an isolated corner of Cuba -- and said Monday's actions were in pursuit of that goal.

Critics of the military commission system, which was established specifically to deal with the detainees at Guantanamo, contend that suspects are not given some of the most basic protections afforded people prosecuted in American courts. That situation, critics say, serves as a recruitment tool for terrorists.

Obama's administration has enacted some changes to the military commission system while aiming to close down Guantanamo.

More than two dozen detainees have been charged there, and so far six detainees have been convicted and sentenced. They include Ali Hamza al-Bahlul, Osama bin Laden's media specialist, who told jurors he had volunteered to be the 20th Sept. 11 hijacker. He is serving a life sentence at Guantanamo.

Meanwhile, the first Guantanamo detainee tried in civilian court -- in New York -- was convicted in November on just one of more than 280 charges that he took part in the Al Qaeda bombings of two U.S. embassies in Africa. That case ignited strident opposition to any further such trials.

The Justice Department had planned to have Mohammed's trial in New York, but Obama bowed to political resistance and blocked it.

Under Obama's direction Monday, Defense Secretary Robert Gates issued an order rescinding his January 2009 ban against bringing new cases against the terror suspects at the Cuba prison. Gates said the U.S. must maintain the option of prosecuting alleged terrorists in U.S. federal courts, but in his order Monday he also said the review of each detainee's status had been completed and the commission process had been reformed to address legal challenges.

Monday's announcement also included a process for periodically reviewing the status of detainees held at the prison. That's an effort to resolve one of the central dilemmas at Guantanamo Bay: what to do when the government thinks a prisoner is too dangerous to be released but either can't prove it in court or doesn't want to reveal national security secrets in trying to prosecute him? The answer, the White House said, is that the U.S. will hold those men indefinitely, without charges, but will review their cases periodically. However, if a review determines that someone should be released, there's no requirement that he actually be freed.

Senate Judiciary Committee Chairman Patrick Leahy, D-Vt., criticized the new process, saying it does little to change the legal shortfalls of the military commissions. The process, he said, "falls far short of core constitutional values by failing to provide judicial review of cases considered by the review board or guaranteeing meaningful assistance of counsel" to the suspects.

The administration also announced support for additional international agreements on humane treatment of detainees. The White House said that would underscore to the world its commitment to fair treatment and would help guard against the mistreatment of U.S. military personnel should they be captured.