Fox News Flash top headlines for November 17

Fox News Flash top headlines are here. Check out what's clicking on Foxnews.com.

The greatest, underreported story on the planet right now is the lack of any new coronavirus bill that can become law.

What’s even more extraordinary is that there wasn’t a coronavirus bill over the summer. Nor early fall. And the prospects of a coronavirus deal during the lame-duck Congress are dim.

COVID-19 pulses. And it hasn’t altered the political landscape on Capitol Hill.

CONGRESS FACES TIGHT DEADLINE FOR CORONAVIRUS RELIEF, SPENDING DEALS

Don’t forget that House Speaker Nancy Pelosi, D-Calif., and Treasury Secretary Steve Mnuchin spoke, nearly every day, for weeks in an effort to secure a coronavirus deal. Weeks.

Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell, R-Ky., is still pushing his smaller, $500 billion coronavirus bill. Senate Minority Leader Chuck Schumer, D-N.Y., described that bill as “emaciated” last week.

And Pelosi is getting an earful from moderate Democrats – some of whom lost – for not advancing a scaled-back coronavirus bill before the election. Pelosi originally wanted a $3.4 trillion package. But she slid to a $2.2 trillion price tag. Mnuchin came up to about $1.9 trillion. Then Senate Republicans completely threw Mnuchin under the bus on that proposal.

President Trump was all over the map on what he wanted to do. He ordered Mnuchin to break off talks with Pelosi – which never happened. Then, erratically, a couple of days later, the president said he wanted to spend more than Pelosi – regardless of what Senate Republicans wanted.

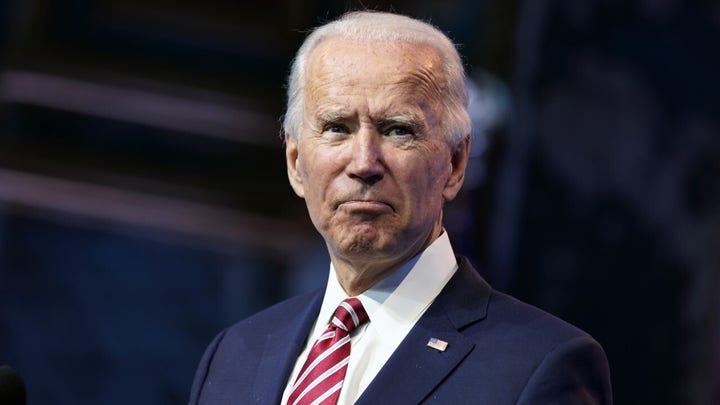

BIDEN PLEDGES TO ROLL BACK TRUMP'S TAX CUTS: 'A LOT OF YOU MAY NOT LIKE THAT'

Moderate Democrats and Republicans pushed Pelosi to do a bill in the $2 trillion range before the election. Pelosi balked at those prospects. It’s possible the House could have passed such a measure with a coalition of Democrats and Republicans somewhere in the middle. But Pelosi probably would have infuriated liberals had she agreed to such a measure. In fact, Pelosi called her original, $3.4 trillion bill “perfect.”

Regardless, a middle-of-the-road bill never had a chance in the Senate.

Still, some wonder if Pelosi missed her chance to move a bill before the election. It would seem that McConnell is in the driver’s seat now – having sat out the daily telephone calls between the speaker and Mnuchin.

Those proved to be a colossal waste of time.

Pelosi is now reaffirming her commitment to a big bill, arguing that her position never changed. And Pelosi and Schumer are now trying to refocus attention on Republicans.

Voters spurred House Democrats on Election Day. Senate Democrats may emerge from this cycle securing a net pickup of one seat. So Pelosi and Schumer are trying to train the public’s attention on coronavirus. They note that Senate Republicans are fixated on something else since returning to Washington: contested election results.

“Instead of working to pull the country back together so we can fight our common enemy, COVID-19, Republicans in Congress are spreading conspiracy theories, denying reality and poisoning the well of our democracy,” said Schumer.

It’s possible the Senate may entertain yet another coronavirus bill. But any deal may have to wait until there’s a new Congress and a new president. Both sides may look for a new administration to broker a deal.

BIDEN PLEDGES TO HIKE TAXES ON AMERICANS EARNING MORE THAN $400K

“At least we will know where the administration stands,” said one senior Senate GOP aide of the Biden administration.

The wild convulsions of Trump and his position on a coronavirus bill at any one time was like playing a video game. That made negotiating a package a near impossibility.

Also, the House and Senate must come to an agreement to fund the government by Dec. 11. And waiting in the wings is the annual defense policy bill. The House and Senate must resolve their differences in the legislation. But both versions of the bill would rename military bases and facilities named after Confederates. Trump has threatened a veto of the legislation.

That veto warning is important. Especially in the context of a coronavirus bill.

Even if there was an agreement on a coronavirus package on Capitol Hill, would Trump sign it? The virus surges and yet there’s little if any engagement from 1600 Pennsylvania Ave. on the subject. Instead, there’s speculation about a Trump 2024 bid. This comes even as White House Chief of Staff Mark Meadows contracted the virus. No one has heard from Mnuchin in days. And if Mnuchin were engaged in the talks, there’s doubt on Capitol Hill that going through the Treasury secretary is the best route to work out a package during the lame-duck Congress.

“This is a red alert. All hands on deck,” said Pelosi. “An emergency of the highest magnitude. Yet our Republicans want to focus elsewhere.”

There’s scant chatter at all from any Republicans about what to do next. Many GOPers are still sequestered in their own version of political lockdown, afraid to do much of anything until Trump concedes or the election is finalized.

“Congress must now do a Covid Relief Bill,” screamed the president on Twitter over the weekend after days of silence on the issue. “Needs Democrats support. Make it big and focused. Get it done.”

This is a vacant appeal.

Divisions over cost remain.

“It seems to me that the snag that hung us up for months is still there,” said McConnell.

A measure of this magnitude and importance – even if it’s “small” (remember, that in the grand design of things, a $500 billion congressional bill is actually gigantic) – requires direct presidential intervention, deep negotiation and the investment of both Pelosi and McConnell. And frankly, doing such a measure during the lame duck probably needs the blessing of the incoming administration.

None of that is happening.

Buy-in by President-elect Biden would be of paramount importance. A month after losing to President Bill Clinton in 1992, President George H.W. Bush secured support from both Clinton and congressional leaders as he committed troops to Somalia.

With less than two months left in his term, on this day in 1992 Bush ordered the Pentagon to dispatch 28,000 U.S. Marines to Somalia. At the time, the East African country was being torn apart by a civil war and well on its way to becoming a failed state.

The outgoing president characterized the military mission in humanitarian terms, calling it “God’s work.” He garnered support for the mission from congressional leaders as well as from Clinton, the president-elect. There were similar engagement efforts between the outgoing administration of President George W. Bush and President Obama amid the financial crisis and transition in 2008.

But don’t count on much cooperation right now.

A coronavirus bill likely must wait until next year, despite a burgeoning crisis. And even then, it’s unclear if the House, Senate and President-elect Biden can get on the same page.