About one in every 20 adults in the United States has survived cancer, according to new federal data. In 1971 there were three million cancer survivors living in America. As of March 2015, there are over 14 million, 5 million of which are young adults. About 65 percent of cancer survivors have lived at least five years since receiving their diagnosis, 40 percent have lived 10 years or more, and nearly 10 percent have lived 25 years or longer.

This all means that there is a steadily growing population who are asking the question “What now?”

Cancer forces people to put their lives on hold. It can cause physical and emotional pain, and result in lasting problems. It may even end in death. But many people gain a new perspective on life. It is as if their senses become more finely tuned by facing their own mortality. Their lives take on new meaning.

When I was diagnosed with cancer in 1993, I was devastated. My first reaction was fear, which was soon followed by a crushing sense of feeling all alone.

I felt alienated and estranged from everyone. It was like I was living in a different universe. Susan Sontag described this feeling well when she wrote that the sick person is transported to another country, separate and distinct from the land of the healthy. This became my new normal.

Then, after my treatment concluded, I was surprised to find myself experiencing an anomic terror when my oncologist said, “Ok, you’re good to go. Aren’t you glad you won’t have to see me so frequently?” My first thought: “NO! What am I going to do?” My second thought: Why am I feeling all alone again? I couldn’t get over that empty feeling.

Over time, I began asking other survivors about how they felt when their treatment was finished, and many acknowledged similar feelings. One survivor even gave a name to it, labeling it the "silent phase" of cancer, when the frenetic flurry of treatments and doctors’ appointments is replaced with a gaping silence and an uncertainty about what the future holds.

At this point, survivors are left to their own resources as they attempt to move forward. Family and friends expect the survivor to move on. But, as Dr. Thomas R. Frieden, director of the Centers for Disease Control reflects, “Having cancer may be the first stage, really, in the rest of your life.”

Ellen Stovall, a senior health-policy adviser for the National Coalition for Cancer Survivorship, has written: “With cancer, it’s not ‘death or cure’ anymore … Learning to live with cancer is a very different mindset -- and many need to figure out how.”

Adjusting to my new state took some time and the help of not only a team of sensitive physicians, but also that of a gifted therapist.

I became aware of what really mattered. I focused on what I loved about my work, and tried to eliminate tasks I disliked. I consciously strove to make my family and friends a bigger part of my life. I became a better husband, father and friend.

Cancer became, and many survivors concur, a gift, a catalyst for accepting my limitations, my mortality, and my strengths. I learned that fear, pain and depression may not necessarily be lasting events, but can be viewed as passages to somewhere and something better.

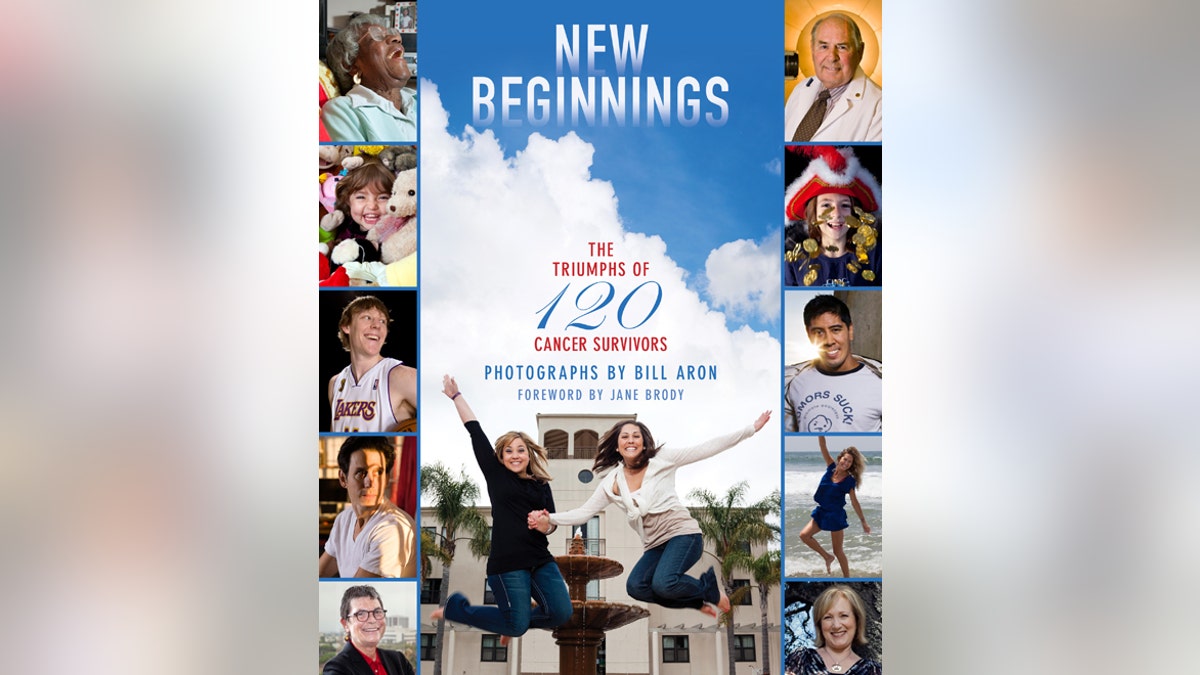

Cancer gave me the opportunity for a new beginning. I wanted to help others, as I myself had been helped. I wanted to create the kind of book I wish had existed when I was diagnosed.

As I spoke with the survivors I photographed for "New Beginnings," I discovered an intriguing combination of fragility and inner strength.

They were fragile in that they had a realistic assessment of what they had lost, and of the obstacles that lay ahead. They had undergone a sometimes painful process of self-examination, honestly facing up to their shortcomings and mistakes, while determining to do better.

Their strength was based in a belief that they could overcome the obstacles, and that their fate was in their own hands.

They did not necessarily think of themselves as being cured; but they felt that they were going to do everything possible to make the most out of whatever time they had left.

The experience of diagnosis and treatment had woken them up, and many were willing, even eager, to change their lives. Some changed careers; some reordered their priorities; others simply reaffirmed that the path they had chosen was right for them.

They changed in other ways as well, altering their diets and taking up exercise. They explored ways to give back to the “cancer community” by raising money, visiting treatment centers, founding survivor organizations, and reaching out to others who had been diagnosed.

Some even felt they were living for those they had known who had died. Their motivation was the belief that they could make a difference.

A good friend recently said to me: “You know, I don’t want to be diagnosed with cancer, but I do wish that I could have that experience of ‘having survived’ so I could make changes in my life.”

Perhaps cancer survivors can demonstrate the way for us all to a better life, to a life well lived.

To quote Megan, age 18: “When they told me the news, it was the worst day of my life. Everything after that got easier. It made me who I am, and I like the person I am today.”