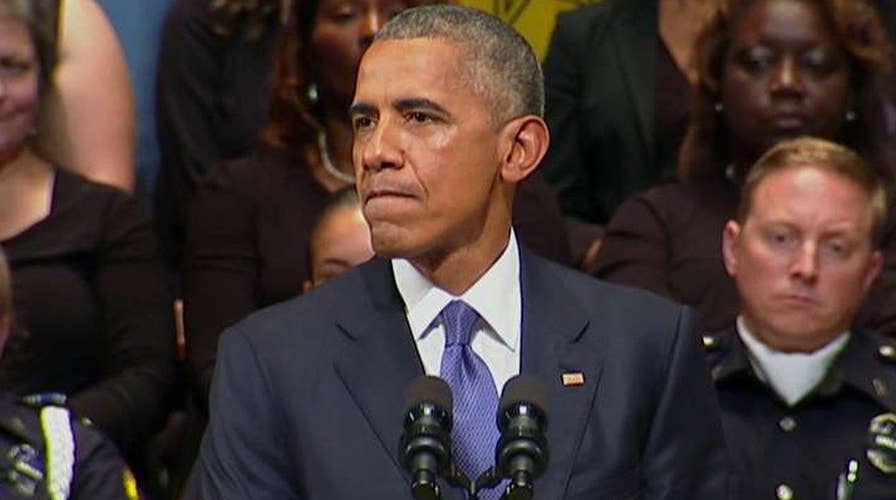

Obama at Dallas service: We are not as divided as we seem

President honors 5 killed officers, offers message of hope

On Tuesday, in Dallas, at the memorial service for the five white cops murdered by a black gunman, President Obama delivered a graceful and eloquent meditation on race relations in America.

The next day, Obama convened a White House meeting of black activists and law enforcement officials to discuss the schism between “the community” and the cops—a discussion that is, in fact, a stand-in for the overall state of black-white relations. The meeting ended in acrimony. "Not only are there very real problems but there are still deep divisions about how to solve these problems,” the president conceded.

On Thursday night, Obama held a televised national conversation that was, again, a failure. Lt. Gov. Dan Patrick of Texas, who is white, accused the president of showing insufficient support for the police. Erica Gardner, the daughter of a black victim of police violence in New York, protested not being allowed to speak at the event. On Twitter she called it “a sham” that exploited the black pain. “They shut out ALL real and hard questions,” she wrote on Twitter.

The past week demonstrated the futility and perils of talking about race honestly, especially in public. Activists and politicians on both sides each have a narrative that suits their interests. To them, a “national conversation on race” is simply an opportunity to deliver a self-righteous lecture that elicits a mea culpa.

A real conversation on race requires a willingness to actually tolerate and even concede the hard truths of the other side.

That’s not going to work. There is too much truth on both sides.

Yes, cops often profile, arrest and abuse young black men. Racist assumptions are pervasive in police practice. There are cops who will do to a black man what they would not to a white man. But it is also true, that young black men get profiled for a reason: They commit a vastly disproportionate amount of violent crime.

Black spokesmen, if they are ready to concede this at all, argue the black crime rate stems from the country’s history of slavery, Jim Crow and racism. They add—and they are right—that white racism may be more subtle today (“systemic” is the term of art) but it is still crippling.

President Obama made this point in Dallas, when he observed that discrimination and bigotry didn’t end with the Civil Rights Act of 1964. But he also said that America had made “unimaginable progress” in his own lifetime. As comedian Larry Wilmore says, when he was growing up in the Sixties a black man couldn’t be an NFL quarterback, let alone the leader of the Free World. Nor could a black man been the Attorney General of the United States, a big city mayor or the chief of police.

Such progress is frustrating to blacks whose rising expectations whose rising expectations have not been completely met. It has also been frustrating to white Americans. A loss of power and status, no matter how undeserved, is always jarring.

Not everyone has made the adjustment to the new state of things, but a great many whites have tried. They have cleaned up their racial language (a lot of blacks would be surprised how rare blatant racial slurs are in white conversation). Once segregated evangelical megachurches now welcome black worshippers. Interracial dating and marriage are no longer taboo. At work, many whites have black bosses.

Some whites resent and resist. Others (I think most) are reconciled or even proud of their own personal progress, and vexed by the refusal of many blacks to grant them, and their country, a recognition of goodwill. “Hey, how racist could America be if a black man is president? And how free of prejudice am I if voted for that president?”

Black activists (and not just activists) find this infuriating. Don’t whites still see their privilege? Can’t they see the discrimination blacks face at the bank, in the justice system, shopping in a department store or driving peaceably along? Don’t they understand how hard it is to give a teenaged child “The Talk” about the danger of dealing with cops?

Blacks don’t know that whites have their own version of The Talk. They, too, warn their sons not to mouth off to cops (police shoot a greater percentage of whites than blacks, according to a recent study published by the New York Times). They caution them to avoid neighborhoods where a white skin can provoke hostility and violence. And they teach their kids to watch what they say, even in jest, at school or work, where real or perceived racial micro-aggressions can result in severe repercussions.

And so it goes.

Black people are tired of being judged and ignored by white people who think equality is a favor. White people are sick of being called racists by people who seem perpetually furious and unwilling to accept good-will as genuine.

A real conversation on race requires a willingness to actually tolerate and even concede the hard truths of the other side. This week President Obama tried to get one started, and failed. It is unlikely that the next president will do better.