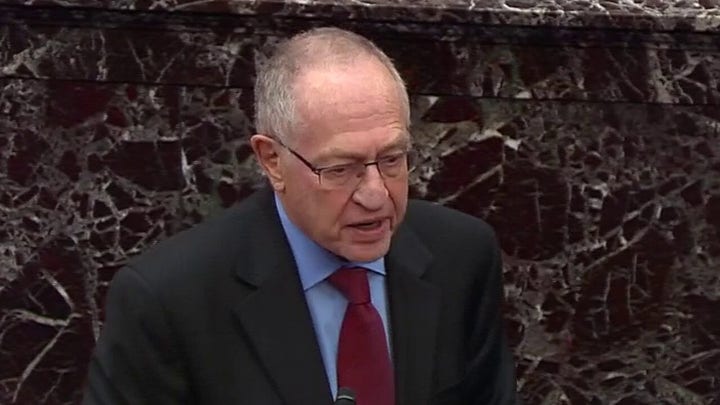

Alan Dershowitz: Current 'scholars' who call for Trump's impeachment 'got woke' since the 19th Century

Alan Dershowitz slammed present-day scholars for changing their legal opinions based on partisan politics and aversion to President Trump.

A politician’s election represents the public interest for one simple reason: the public elected him.

“If a president does something which he believes will help him get elected in the public interest, that cannot be the kind of quid pro quo that results in impeachment,” said Alan Dershowitz, a Harvard law professor and one of the attorneys representing President Trump at his Senate impeachment trial.

Prof. Dershowitz’s comments triggered instant criticism. But Dershowitz’s critics merely revealed their own ignorance about the law, the Constitution, and democracy itself.

HERE ARE THE QUESTIONS 2020 DEMS ASKED DURING TRUMP IMPEACHMENT TRIAL

“This is what you hear from Stalin,” said CNN contributor Joe Lockhart, who served as White House press secretary under President Bill Clinton. “This is what you hear from Mussolini, what you hear from authoritarians, from Hitler, from all the authoritarian people who rationalized, in some cases genocide, based what was in the public interest.”

Stalin and Hitler did not believe elections serve the public interest. They murdered their political opponents. Literally—not metaphorically in landslide elections. And genocide—unlike the impeachment articles against President Trump—is a crime.

Criminal behavior is not in the public interest. The public criminalizes it. For example, Joe Lockhart’s former boss sexually exploited a 22-year old intern inside the Oval Office. Then he lied about it under oath, committing perjury: a felony crime punishable with years in prison. Consequently, he was impeached. But even under those extreme circumstances, the Senate did not expel President Bill Clinton from the White House.

Perjury, like murder, is a crime of moral turpitude. Criminal statutes generally represent the public interest because these statutes are drafted by legislators whom the public elected. The President, likewise, is elected by the public to implement such legislation and fulfill other executive functions.

Members of Congress and the president each represent their respective voters. And, in a democracy, voters are the ultimate deciders of the public interest. A politician who faithfully serves voters’ interests—and wins their election—is serving the public interest.

The limit to this principle is found in criminal statutes and the Constitution. That has been Prof. Dershowitz’s argument all along. Prof. Dershowitz has repeatedly emphasized that “abuse of power” is an invalid impeachment article specifically because it is an unlimited accusation. The Constitution’s minimum standards for impeaching a president require “high crimes and misdemeanors” such as treason and bribery: not merely the abuse of power.

But neither of the two articles of impeachment against President Trump raises any such criminal accusation. Thus, according to Prof. Dershowitz, these articles of impeachment are constitutionally invalid. If legislators want to impeach a president while operating within the boundaries of statutory and Constitutional law, then they must allege and prove criminal misconduct at the level of high crimes and misdemeanors.

More from Opinion

- KT McFarland: You want impeachment trial witnesses? OK, here are questions they should answer about the swamp

- Gregg Jarrett: Trump’s conviction in impeachment trial not justified even if Bolton claims are true

- Dr. Kent Ingle: Iowa Democratic caucuses will show which candidates are best at spinning their extreme agenda

Instead, the House of Representatives accused President Trump of “abuse of power” because “to obtain an improper personal political benefit” he ignored “national security and other vital national interests.”

But by this standard, every President, whether Republican or Democrat, is impeachable. Abuse of power is a cliché accusation that politicians routinely toss at each other.

Here, the alleged abuse of power is that President Trump asked Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky to investigate corruption and election meddling as a quid pro quo for timely receiving certain military assistance from the U.S. government. That is why Sen. Ted Cruz, R-Texas, asked Prof. Dershowitz, “As a matter of law, does it matter if there was a quid pro quo?”

Of course, it is self-evidently in the public interest for voters to know about corruption and election meddling. But the “personal political benefit” to President Trump under this quid pro quo is that it would reduce voters’ support for Democrats if voters saw that Ukraine meddled in the U.S. presidential election to help Democratic candidate Hillary Clinton, and also if voters saw that Vice President Joe Biden enjoyed a conflict of interest when his son, Hunter Biden, was paid a fortune to sit on the board of a politically-connected Ukrainian energy company while Vice President Biden oversaw Ukraine policy.

CLICK HERE TO GET THE OPINION NEWSLETTER

Whether there was a quid pro quo or not, elections can remedy or ratify such alleged abuses of power. The decision belongs to voters: not to legislative factions and certainly not to unelected bureaucrats.

To be sure, voters elected both the President and the legislative faction that is trying to remove him.

CLICK HERE TO GET THE FOX NEWS APP

That is why fidelity to the law matters. The law of high crimes and misdemeanors is the constitutional tiebreaker that resolves this impasse between the duly-elected House of Representatives and the duly-elected President.

And the 2020 election is the tiebreaker that will resolve whether the President and his opponents each remain in office for the following term.