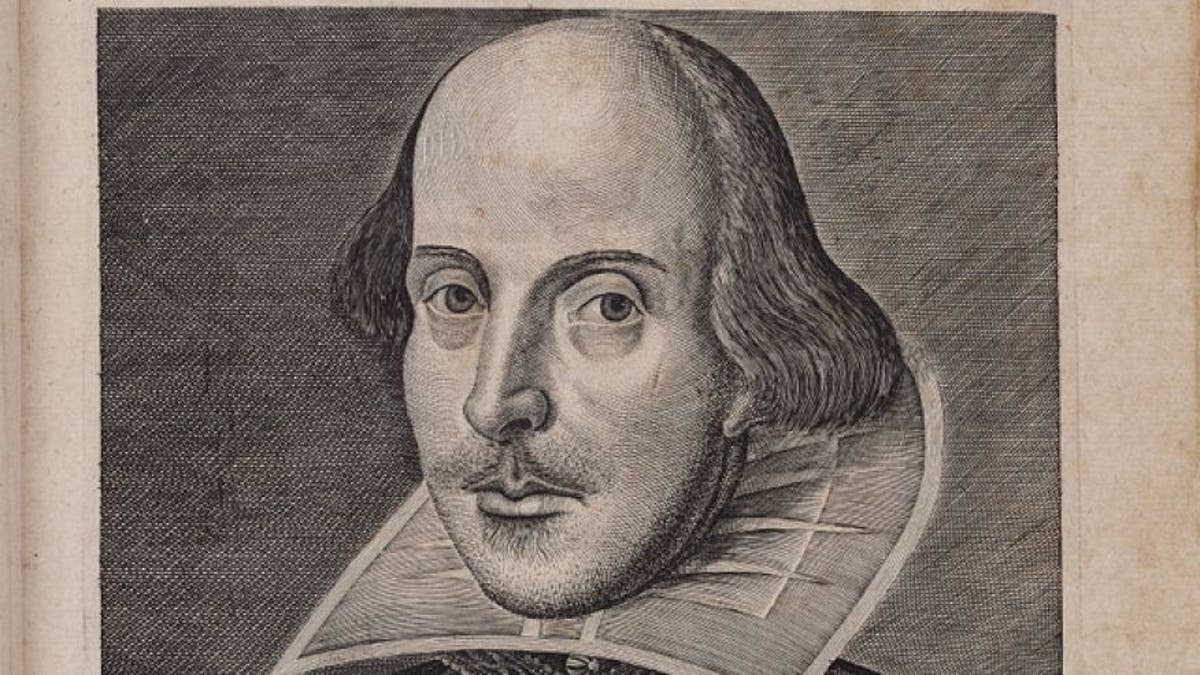

This engraving of a man identified as William Shakespeare appears on the front of a First Folio of Shakespeare's plays dating from the early 17th century (Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Yale University)

Friday I set off to Stratford-upon-Avon for the annual Shakespeare Birthday Celebrations in his home town.

No one knows exactly when Shakespeare was born on but for a long time April 23 has been the accepted date, coincidentally both the day we are sure he died on and the day celebrated in England as St George’s Day, the name-day for the country’s patron saint.

This year no one is quite sure what to call the event, since, as it seems impossible not to have noticed, 2016 marks the four hundredth anniversary of Shakespeare’s death and celebrating someone’s death doesn’t sound quite right.

So let’s call this the 400th anniversary of Shakespeare’s legacy and celebrate that.

We often talk about the astonishing nature of Shakespeare’s own imagination, that apparently limitless creativity that the novelist Alexandre Dumas described in a tone of awe: “After God, Shakespeare has created most.”

But what precisely are we celebrating? “Hamlet” and “King Lear,” “Romeo and Juliet” and “A Midsummer Night’s Dream” and all the familiar quotations, of course. But there are two Shakespeare passages that are much in my mind at the moment, neither of them well-known.

The first is from “Sir Thomas More,” a play to which Shakespeare contributed the only scene in his own handwriting to have survived. In the play, the citizens of London, fed up with the number of foreigners in the city, have gathered to demand their expulsion and Sir Thomas More tries to talk them out of their violent intentions. One tactic he tries is to make them imagine they succeed:

Imagine that you see the wretched strangers,

Their babies at their backs, with their poor luggage

Plodding to th’ports and coasts for transportation,

And that you sit as kings in your desires […]

What had you got? I’ll tell you. You had taught

How insolence and strong hand should prevail,

How order should be quelled.

The picture of the ‘strangers’ – we know them as refugees and migrants – is appallingly familiar now, an image of terrified and desperate people fleeing a country hostile to them. More’s tactic succeeds and the noisy crowd quietens. Then More goes further, asking the crowd to imagine that the King’s response to their treasonous uprising is to banish them: ‘whither would you go? / What country, by the nature of your error, / Should give you harbor?’. If they arrive in any other country in Europe, ‘why, you must needs be strangers’, and the local population might ‘Whet their detested knives against your throats’:

…what would you think

To be thus used? This is the strangers’ case,

And this your mountainish inhumanity.

We often talk about the astonishing nature of Shakespeare’s own imagination, that apparently limitless creativity that the novelist Alexandre Dumas described in a tone of awe: “After God, Shakespeare has created most.” But here, through Sir Thomas More, he asks the rioters to imagine and, by so doing, makes us imagine too, creating two visions of a future, both premised on the success of the rioters in ridding the city of the ‘strangers’.

It is the second vision, of the protesters themselves becoming ‘strangers’, that is the one that sticks with me.

As I watch and listen on television to those across Europe and across the U.S. who would lock their gates against all outsiders, I have some sympathy with their multiple fears, not least the fear of terrorism that Shakespeare’s Londoners did not have a reason to feel.

But Shakespeare makes us move from the secure response of sympathy to the much more difficult one of empathy, of feeling what it would mean to be that other person, of exchanging our position for theirs in ways that go far beyond simply recognizing our common humanity, imagining instead becoming ‘strangers’ desperate for a new home and acceptance by the local population.

By achieving what he asks of us, we do not necessarily define what should be done but we can change the frame of mind within which those decisions could be taken.

For my second moment I move from the migrant crisis to an election. At one point in “Coriolanus,” when the hero, as part of the political process of election to being a consul of Rome, has to stand in the marketplace, asking the citizens to give him their votes, he asks one of them what is ‘the price of th’consulship’, he gets an unexpected answer: ‘The price is to ask it kindly.’

Coriolanus thinks the citizen means he has to ask nicely, to say please, to be humble as opposed to his usual arrogant contempt for the ordinary people. But the citizen – and Shakespeare – is asking for something more: for Coriolanus to accept that he is of the same kind, that he is like them and not a different order of human being simply through his status.

Politicians of both parties always claim to be like the voters but I don’t trust their rhetoric. If they acknowledged our likeness, they wouldn’t make their stump speeches into the performances they are. Like Coriolanus in the market-place asking for the plebeians’ ‘voices’, those wanting to get elected have to go through civic rituals as persuasively as they can but I rarely see signs that they know the true price of asking ‘kindly’.

When I watch the parade wind through the streets of Stratford-upon-Avon this weekend, unfurling flags of many nations, it is the power of moments like these that I shall be thinking of, language that reminds me of the global legacy of the small town’s greatest son and, for all the kitsch of the event, I’ll know how much that legacy deserves celebrating.