What is folklore in the 21st century?

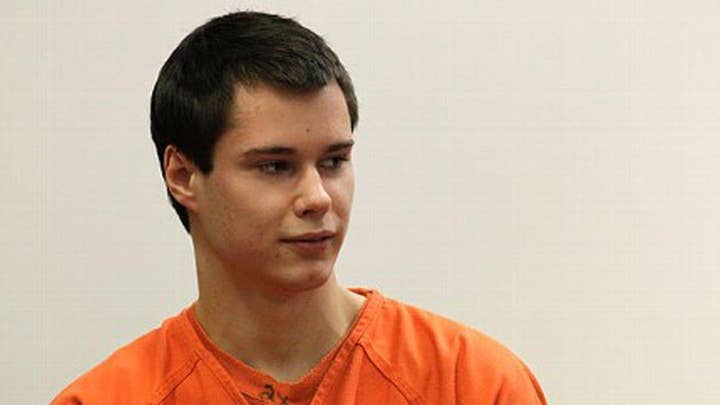

Colton Harris-Moore is a former fugitive who became a modern-day folk hero. He was dubbed the “Barefoot Bandit” for an unforgettable cross-country crime spree he committed as a teenager.

Harris-Moore began breaking into homes and cabins on Puget Sound’s Camano Island, court records showed.

The "Barefoot Bandit" developed a huge following online, with supporters tracking his movements on social media.

Harris-Moore was sentenced in 2012 to seven years in prison for a series of crimes he committed barefoot, which began after he escaped from a juvenile halfway house in 2008.

He was ultimately captured after crash-landing a plane that he stole in Indiana and flew to the Bahamas.

Here is his story.

CURRENT LIFE

After his notoriety as a celebrity criminal, Harris-Moore is less in the spotlight these days.

In December 2015, he endorsed Donald Trump for president on his personal blog.

He also now has a Twitter account, where he describes himself as: "Pilot/Entrepreneur/Boyfriend/fmr. international fugitive."

"The past is done; the future is unwritten. Life is what you MAKE IT!" he writes in his bio.

However, there’s a catch to his contemporary brand.

2019

Last year, the “Barefoot Bandit” was ordered to complete his probation after requesting he be allowed to visit friends overseas and accept work outside Washington state to do influencer-type engagements as a motivational speaker.

Harris-Moore claimed that the work would help him pay off the more than $1 million in restitution he still owes to victims of his crimes.

Harris-Moore was sentenced in 2012 to more than six years in prison plus three years of supervised probation after being convicted following a string of crimes that included dozens of thefts and burglaries, the smashing of vehicles and the crash-landings of three stolen airplanes.

His nickname came from the sketches of a barefooted footprint that he often left behind at the crime scenes, and he even committed some crimes without wearing shoes or socks, reports said.

2016

The 6-foot-5-inch Harris-Moore pleaded to get out of prison early to work at his lawyer's firm during the summer.

His attorney John Henry Browne told the Seattle Times he and his client agreed years ago that Harris-Moore would work part-time at his law firm while looking for a full-time job, and, eventually, going to school.

The job was to answer phones and perform clerical work, according to the lawyer.

The attorney said he had sympathy for his client.

“He might have a touch of Asperger’s, a little bit, because he can focus on something and master it,” Browne said of Harris-Moore’s ability to learn how to fly airplanes by simply reading the manuals. “He’d never even flown in a commercial plane."

The attorney said his client’s delinquency began out of necessity -- not evil.

“He started down the path of criminality, if we can call it, literally to eat,” Browne said. “When he was younger, his mother was not taking care of him, and was using food stamps for beer and things.”

His mother died that summer.

Harris-Moore said he wanted to cryogenically freeze his mother with the hope that medical advances would allow her to be revived and her lung cancer treated. He later said that he hadn't been able to raise enough money for the procedure.

He was freed from his work-release program that winter.

2014

Harris-Moore's story was told in a feature-length documentary, "Fly Colt Fly: Legend of the Barefoot Bandit," which premiered in 2014. It blended interviews with animation.

The graphic-novel style animated documentary was made by Canadian filmmakers and shot during a six-week shoot in the Puget Sound and San Juan Islands.

Unrelatedly, Harris-Moore had previously sold the movie rights to his story in the hopes of raising enough money to pay $1.3 million in restitution to his victims.

2012

He was moved out of solitary confinement and into the general inmate population at another prison in Washington state, corrections officials confirmed during the summer.

He had spent three weeks in "intensive management," most of which was at the Walla Walla State Penitentiary alongside inmates facing the death penalty. It was for his own protection as a high-profile convict, Washington Department of Corrections spokesman Chad Lewis said.

"Somebody might want to make a name for himself by saying, 'I took down the Barefoot Bandit,'" Lewis had said.

Harris-Moore had been in solitary confinement at Walla Walla since he arrived in April, and he was allowed out of his cell five times per week, for an hour each time.

2011

When he was sentenced in December, Judge Vickie Churchill said: "This case is a tragedy in many ways, but it's a triumph of the human spirit in other ways."

She described Harris-Moore's upbringing as a "mind-numbing absence of hope," and believed he was genuinely remorseful and contrite.

In a statement provided to Churchill, he said his childhood was one he wouldn't wish on his "darkest enemies."

Still, he said he takes responsibility for the crime spree that brought him international notoriety.

2010

He was apprehended in a hail of bullets in the Bahamas in 2010.

After he was captured, his arrest caused sadness in his fans.

Some of his more than 60,000 Facebook fans posted disappointed messages, while others promoted T-shirts and tote bags with the words "Free Colton!" and "Let Colton Fly!"

"I feel like it would have been good if he got away because he never hurt anybody, but then he was running from the law," said Ruthie Key, who owns a market on Great Abaco Island and let Harris-Moore use her wireless Internet connection in July 2010.

"He seemed very innocent when I spoke with him at the store. I don't think he'd hurt anybody," Key said.

CLICK HERE TO GET THE FOX NEWS APP

Harris-Moore was a skilled outdoorsman who honed his abilities growing up in the woods of Camano Island in Puget Sound about 30 miles north of Seattle.

Harris-Moore's mother, Pam Kohler, had said that he had a troubled childhood. His first conviction, for possession of stolen property, came at age 12. Within a few months of turning 13, he had three more.

The Associated Press contributed to this report.