“High School Pregnancy Pact Revealed! 90 girls either pregnant or have just delivered!” Stripped of that catchy headline, the melancholy story of Frayser High School in Memphis is way too familiar.

As we discovered last weekend during a ‘Geraldo-At-Large’ probe of that high school in Tennessee, with its overwhelmingly poor, largely African-American student body, this urban district is coping with an epidemic of babies having babies; 26 percent of Frayser’s girls becoming pregnant while still in high school, contrasted with about 10 percent of all teenage students nationwide.

And while proportionally, more black teens get pregnant, 58 percent according to the National Campaign to Prevent Teen Pregnancy; Latinas, at 53 percent are rapidly closing the gap. And because America boasts more Latina than black teens, we already have the highest absolute number of babies born to babies, another sad addition to our list of dubious distinctions, along with our rate of high school dropouts.

Although there is a distinct correlation between the two, let’s deal with one catastrophic social problem at a time; so education aside, back to teen pregnancy.

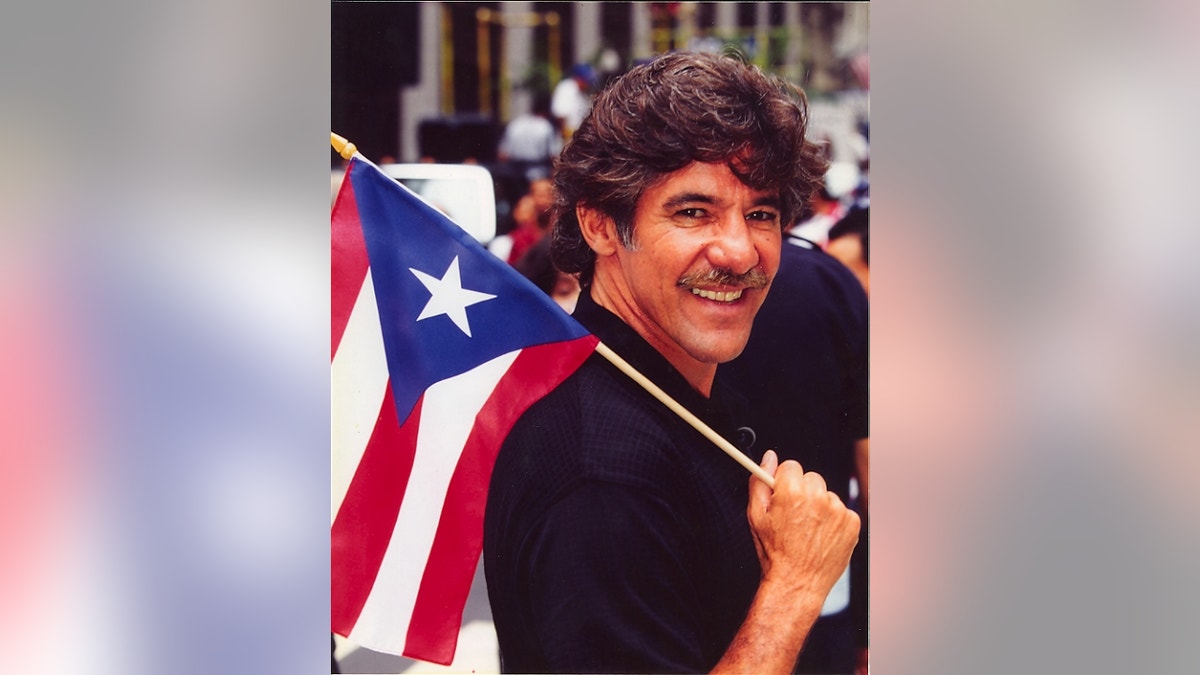

As in many agrarian societies, Latinos have historically had large families. This was a function of everything from religious conservatism to practical economics. My dad Cruz Rivera, for instance, was the sixth of seventeen children born to Juan and Tomása Rivera of Bayamon, Puerto Rico.

“How could you have so many children?” I remember asking my grandmother, a woman of enormous patience and good humor who wore her snow-white hair pulled back, contrasting dramatically with her angular, chocolate-colored face made leathery by the sun. “Times were different then,” this strong woman who lived until just shy of her 99th birthday replied in fabulous understatement. Abuela was referring to the family’s modest lifestyle in the sugarcane and coffee economy that dominated the island in the days before a series of ill-advised tax breaks brought U.S. industry to the Commonwealth and ended an era.

Although she started having babies as a young teenager, in Abuela’s times each child represented another hand to help in the fields or the family bodega or repair shop if you were a boy or with the housework or raising the younger children if you were a girl. Times have changed. Nowadays, with our largely urban existence, each successive child is an additional burden in poor families; each birth making it more likely that the mother stays trapped in the cycle of government dependency that characterizes so many contemporary Latino lives.

I remember a not-too-distant conversation with a pregnant 15-year-old whose mother was 30 years old at the time, and whose grandmother, 45. The conversation revolved around a discussion of abortion, which, like birth control, is one of those ‘don’t go there’ topics in too many Hispanic family lives.

Distressingly, the reason the pregnant child gave for not getting an abortion or giving her child up for adoption was not morality or belief in the sanctity of life or the tenets of her Catholic faith. It was that all of her friends were doing it, (i.e., having sex and, often getting pregnant). And that, as her mother and grandmother before her, she knew she could get sufficient government assistance for her dependent children to live a more or less independent life. What about your future? I asked. I’m going to be cleaning houses anyway, she answered with a flat tone that spoke eloquently to her own limited expectations.

The challenge for our policy makers, particularly Latino elected officials and educators, is to break the malignant cycle of dependence by first admitting we have an enormous problem on our hands. We are great at celebrating Cinco de Mayo or the Puerto Rican Day Parade, but lousy at admitting that we are the casualties, not the winners of the War on Poverty.

What to do about it?

1- As a society, we have to stop giving our boys a free pass and start holding them at least economically responsible for the children they bring into the world. Pierce the bubble of strutting machismo by requiring that every single birth certificate has a father’s name attached. It takes two to tango and that boy/father must pay for his pleasure. It might make him think twice before pretending he’s on the cast of ‘Latino Skins’.

2- We have to recognize that sex education that teaches abstinence only rather than dealing realistically with our teenagers’ lives is pathetically unsuited to the real world. Most of these kids are going to have sex before they are either adults and/or married, and if we don’t want them having babies, we should let them know exactly how biological reproduction occurs.

3- We have to challenge the notion that living off Aid to Dependent Children, food stamps or other entitlements is the best future society can offer. We must inspire and motivate our girls and boys with mentoring, apprenticeships, scholarships and/or jobs programs that give them a chance to earn some righteous money, while learning a useable skill.

Another big reason Latinas use birth control less frequently and reject abortion and adoption more often than other kids is simply the financial inability to access classes and clinics that might make a difference. But when I mentioned religion and the social conservatism of many Latino families as an impediment to reducing teen pregnancy rates, I did not mean to denigrate those characteristics. We are who we are and I’m proud of it. But the days of the finca (the family farm) of my grand parents’ day are largely past. We must confront the fact that as a result of our manners and shyness, our folks don’t have the kind of frank conversations with our own children that might make a difference.

Follow us on twitter.com/foxnewslatino

Like us at facebook.com/foxnewslatino