A novelist's look at the Reagan years

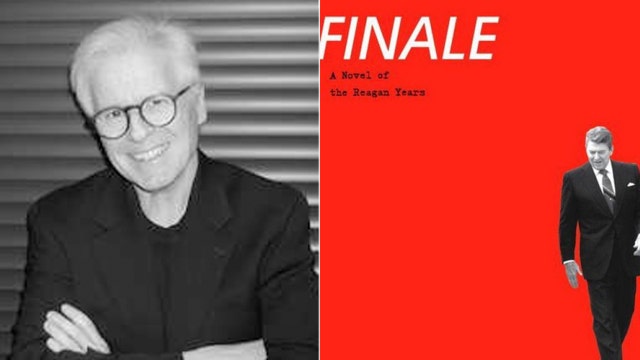

Novelist Thomas Mallon uses the Reagan years as the setting for his latest book.

As one of the most accomplished novelists and essayists in American letters – so good and universally respected he is still allowed, even as a declared conservative, to write for The New Yorker – Thomas Mallon has made a career out of getting under people’s skin. Or perhaps, more aptly: inside their skin.

Mallon is one of the leading practitioners of historical fiction: novels set in distinct times and places, where made-up characters interact with real historical figures, re-imagined in settings where the reader enjoys access to their private thoughts as conjured by the novelist.

For Mallon, the terrain has shifted from the Civil War to the Watergate era, but his methodology has remained remarkably consistent (and well received): to tackle signal eras and episodes through the eyes of peripheral characters, who lead readers into the salons and offices and bedrooms where history is really made.

For his latest novel, however – “Finale: A Novel of the Reagan Years,” published in September by Pantheon – Mallon found himself stymied by the charismatic yet famously elusive fortieth president. From the outset, Mallon was determined to avoid the fate of Edmund Morris, the acclaimed historian who served as Reagan’s authorized biographer and whose ensuing book "Dutch: A Memoir of Ronald Reagan" (1998) was roundly criticized for its resort to the use of a fictional character.

At moments he seemed very, very large and profound; at other moments he seemed silly; at other moments he just seemed mystifying.

Morris, who had won the Pulitzer Prize for a biography of Theodore Roosevelt, was one of Reagan’s “most vexed biographers,” Mallon told me in a recent visit to “The Foxhole.” “I think Reagan drove him sort of crazy as a subject.”

Yet as Mallon began work on “Finale” in 2011, he felt Reagan’s inscrutability getting the better of him.

MALLON: I never found it hard to write Nixon from the inside out, to make him a point-of-view character, as we say in the lit biz. And I could not do that with Reagan. I knew I was not going to be able to do that from the first weeks when I was writing the book – that when I was attempting to go inside him, I was defeated, the way I think many biographers have been defeated by Reagan. At moments he seemed very, very large and profound; at other moments he seemed silly; at other moments he just seemed mystifying. And so the remoteness that many people have attributed to Ronald Reagan – even Nancy Reagan, for all of their vaunted closeness – that told me early on that I had to write him in a different way, with a different method…

ROSEN: What did that speak to about the man? Was it deliberate? Was it affected? Was it just the way he was? How did that come to be, do you think?

MALLON: I think part of it was natural. I think there was an eeriness to Ronald Reagan. And people used to talk [about how] even when he was a young actor in Hollywood, when he would go onto a soundstage, nobody would hear him arriving. He almost glided. And so I think some of it was natural to him. But I think there was also a great deal of theatricality to him. He was trained. He once said he didn't know how anybody could be president without having been an actor. And I think he knew how to “work it,” as they say in showbiz. But you know, I think one of the reasons the Reagan administration was so consequential – whether you liked it or not, it was a big presidency – and some of that is attributable to the convictions that Reagan brought to the office. But some of it I do think is attributable to the mystery around him.

There are Mallon Freaks out there, fans who have read just about everything the man has ever written – including his rare foray into book-length non-fiction, “Mrs. Paine’s Garage and the Murder of John F. Kennedy” (Mariner Books 2003), about the woman who rented a room to Lee Harvey Oswald and in whose garage the rifle used in the JFK assassination was stored the night before.

At some point, the sheer prolificity and high caliber of the Mallon Canon will surely attract the attention of a literary biographer, someone who can tell the story of this gregarious and keenly perceptive writer whose novels have captured so much of American history.

All I ask, when that day comes, is that Mallon’s biographer should elect to employ the Mallon Method, and choose, as the peripheral character who leads the reader into the larger theme, the humble figure who has twice now had the privilege of welcoming Mallon into “The Foxhole.”

Click here to watch the full episode of “The Foxhole” with guest Thomas Mallon.