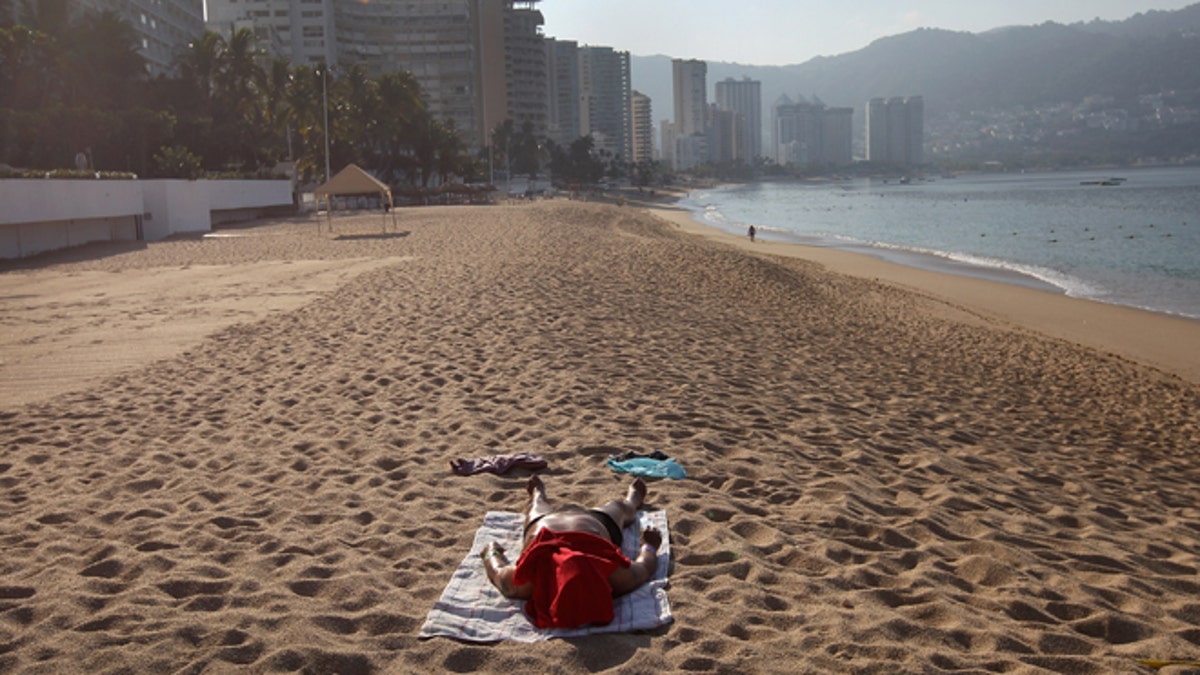

ACAPULCO, MEXICO - MARCH 02: A lone tourist lies out on the beach early on March 2, 2012 in Acapulco, Mexico. Drug violence surged in the coastal resort last year, making Acapulco the second most deadly city in Mexico after Juarez. One of Mexico's top tourist destinations, Acapulco has suffered a drop in business, especially from foreign tourists, due to reports of the violence. Toursim accounts for some 9 percent of Mexico's economy and about 70 percent of the output of Acapulco's state of Guerrero. (Photo by John Moore/Getty Images) (2012 Getty Images)

From retirees to surfers to people looking for affordable beach property, the allure of Mexico’s Pacific coast has drawn Americans south of the border for decades.

But because of Mexican laws barring foreign home ownership along the coast, having that ocean-side oasis has eluded many Americans. Those that have been able to acquire a beachfront property have had to finagle through Mexico’s hazy legal system.

A proposed constitutional change in the halls of Mexico’s Congress, however, could make it easier for foreigners to own land on Mexico’s coast – a move that has been trumpeted by retirees who want Mexico’s Pacific coast to be the next retirement Mecca. But in Mexico, the proposal has divided Mexicans between those who believe these northern snowbirds will bring a boost to the local economies and those that see it as a blasphemous insult to Mexican sovereignty.

“[I]t’s going to be good for a lot of people here,” Artemio Rosas, the owner of a surf shop and real estate broker in the Pacific coastal town of Arroyo Seco, told the Los Angeles Times. “Especially for the poor.”

Mexican law currently prohibits foreigners from owning residential property in what is known as the restricted zone – an area that extends 31 miles inland from the coast and 62 miles from the border. In May, however, Mexico’s lower house approved a proposal to lift the ban, and the move is now poised to pass through the country’s upper house before heading to state legislatures.

While foreigners would still be barred from owning land on Mexico’s ejidos – farming communities that sprang up in the wake of the Mexican revolution – supporters of the constitutional change argue that move would bring about a rush of foreign investment and do away with the tricky trusts called fideicomisos, which foreign investors have had to enter into to have property in the restricted zone. With these trusts, foreign buyers can live on the land but the ownership title is held by the Mexican bank – a move that some say scares off potential buyers.

The proposed change is part of larger expansion under Mexican President Enrique Peña Nieto of permitting foreign interests into the country’s once-tightly controlled economy. The proposals have angered many Mexican nationalists – even many in Peña Nieto’s Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI) – who view foreign investment as a breach of the country’s national sovereignty.

“It is the fall of yet another nationalistic token in Mexico,” George W. Grayson, a comparative politics professor at the College of William and Mary, told Fox News Latino.

Earlier this year, Peña Nieto proposed opening Pemex, the country’s state-run oil company, to private and foreign investment, claiming that the company’s outdated and poorly maintained equipment is hindering the country’s chances of dredging up oil in the deep waters in the Gulf of Mexico.

Peña Nieto has the political capital and votes in congress to put through a constitutional change to break the monopoly of Pemex and allow foreign oil companies to look for oil in the deep Gulf waters,” Duncan Wood, the director of the Mexico Institute at the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars, told Fox News Latino in August.

Companies such as ExxonMobil and Petrobras – the Brazilian oil giant that seems like a regional and ideological fit with Pemex – have expressed interest in drilling in Mexican waters. Telecom billionaire Carlos Slim has also given his attention to becoming involved in his country’s oil industry.

Along with the national sovereignty issue, some analysts worry that widespread coastal development by foreigners would also bring about a major, negative environmental impact – especially in the wake of last month’s deadly topical storms.

“There is a clear downside in that the Mexican government is extremely lax concerning its environmental laws,” Grayson said. “The storms took a toll but the damage was exacerbated because there has been a prodigious amount of coastal development that has cut down trees, destroyed beachfront dunes and drained important wetlands.”

Grayson added that while Mexican supporters may believe that Americans – and their money – will suddenly flood into Mexico, they should be wary of this given the bad public relations the country has recently received as it struggles in its battles against drug cartels.

“Some of the most desired properties are in some of the most violence-infested areas,” he said.

And for jobs in the tourism and resort sector, most of them won’t be going to Mexicans but to foreigners as well – except these expatriates will come from the south, not the north.

“There will be some job creation, but it will come up in the hands of foreigners like Guatemalans and Hondurans, who will do the jobs Mexicans don’t want,” Grayson said.