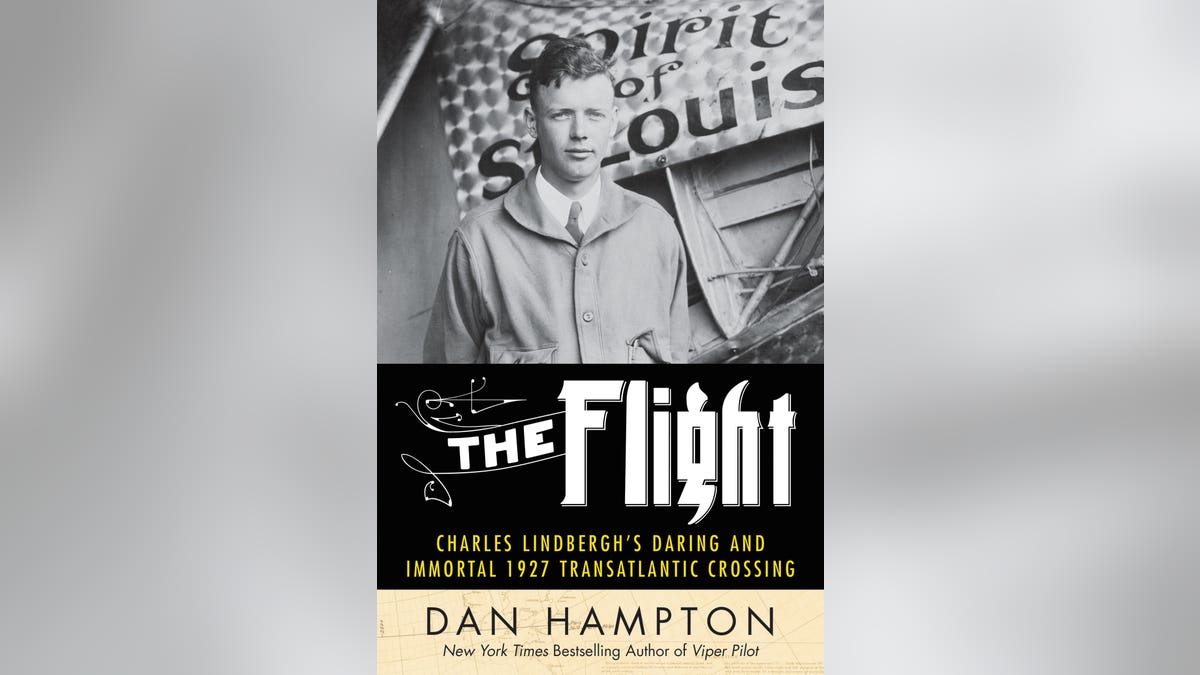

(Library of Congress)

Ralph Waldo Emerson wrote that "to be great is to be misunderstood," and no doubt Charles Lindbergh would have wholeheartedly agreed. It began on May 20, 1927, as the twenty-five year old pilot lifted off from Long Island's Roosevelt Field, turned northeast, and flew the 3,610 miles that altered his future and our world forever. Though the Atlantic had been crossed piecemeal and by airship, no one had flown non-stop from New York to Paris in a fixed wing aircraft. Two French pilots made the attempt but vanished without a trace, and no one had yet embarked alone - except Lindbergh. A prior Army pilot, he had previously barnstormed and flown airmail knowing that the success of this flight would prove the viability of commercial air travel.

Lindbergh, known as "Slim" to his few close friends, would fly more than thirty-three hours in a tiny cockpit above the vast, empty ocean. After landing in Paris at 10:22 PM on May 21, his quiet, unassuming nature immediately endeared him to the French; politely refusing their offer of 150,000 francs, he insisted it be donated to the widows of fallen aviators. Lindy's own countrymen were equally enamored and 300,000 of them turned out on a steamy, Saturday June afternoon to welcome him home. But it wasn't just the flight; at last, America had a hero again. A man untouched by political corruption, or avariciousness self-promotion. Following the scandalous 1920's, Americans were ecstatic and emotionally renewed to have a public figure who did not lie, twist words, or obfuscate the truth. A man they could truly admire.

Lindbergh, ever the reluctant celebrity, stuck to his principles and continuously reminded the adoring world that his passion was aviation. Like Raymond Orteig, the hotelier who had put up a $25,000 prize for completing the flight, Slim hoped that bringing cultures closer together would increase mutual understanding and tolerance. Perhaps future disagreements would be resolved without bloodshed and the horrors of World War One, or any war, avoided. He staunchly hoped for this, as he continued to believe in the potential of aviation for peaceful purposes.

This desire for peace led to Lindbergh's involvement in the America First Committee and one of the greatest misunderstandings he endured. Formed in early September 1940 during the Battle of Britain, the movement resisted American participation in World War Two. Among the 800,000 Americans who joined the AFC were Walt Disney, Gerald Ford, General Robert Wood, Frank Lloyd Wright, and Sinclair Lewis. They believed, as did Lindbergh, that America had shed enough blood for Europe.

Everything changed the moment Pearl Harbor was attacked on December 7,1941.

With the United States now at war Slim sought to have his officer's commission reinstated so he could fight. This was blocked by President Roosevelt himself, who had never forgiven the pilot for a very public dispute over airmail contracts. So, with no other options Lindbergh became an aviation consultant solving engineering and production issues while personally teaching pilots fuel saving combat techniques. After receiving permission to tour the South Pacific as a technical representative, Slim managed to fly fifty combat missions.

He didn’t have to do any of this.

Charles Lindbergh could have remained safe at home, as so many celebrities and politicians did, but he loved America and would not stand idle while others died for his freedom. Misunderstood? Certainly. Lindbergh was surely complex, a study in contradictions. He loved his family but was often undemonstrative; a natural fighter who abhorred war, yet he fought courageously for his country. Of his personal actions later in life, none but his family are entitled to pass moral judgments.

Regardless, Charles Lindbergh's magnificent flight represented then, as now, the best of American character; honesty, resiliency and, above all else, the courage to meet a challenge and prevail. As he would later write, "A victory given stands pale beside a victory won."