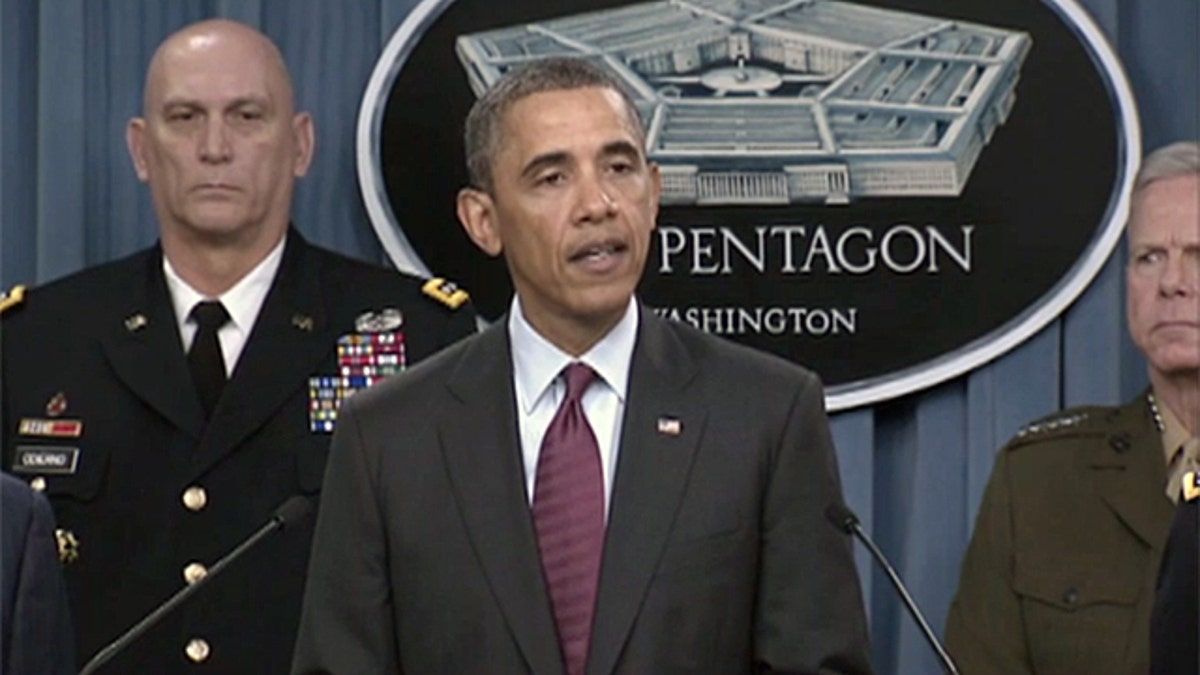

Jan. 5, 2011: President Obama announces cuts to the growth in the defense budget in a rare appearance by a president at the Pentagon briefing room. (FNC)

Iran kicked off the new year with a host of challenges to the United States. Last week, the terrorist state threatened to block the critical Strait of Hormuz to international oil tankers, and on January 9, Iranian president Mahmoud Ahmadinejad arrived to visit Hugo Chavez in Venezuela. Tehran has also accelerated its efforts to enrich uranium that could be used in a nuclear weapon.

In the face of these affronts, President Obama revealed last week his most recent official policy document entitled “Sustaining U.S. Global Leadership: Priorities for 21st Century Defense.”

The report, a result of the president’s directive to cut Pentagon accounts by almost $500 billion or more over a nine year period from 2013-2021 signals the U.S. will take a weaker, more timid approach to defense policy.

U.S. officials rightly describe the growing budget deficit as a national security threat. But as the non-partisan Congressional Budget Office showed in its latest Budget and Economic Outlook, the bulk of the deficit results from $2 trillion in mandatory entitlement spending, which in 2010 stood at almost three times defense spending, which totaled $690 billion, including the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan.

Obama’s plan leaves many questions unanswered about which military programs will survive, but no mystery that many will go.

The plan, combined with the premature U.S. retreat from Iraq amid sectarian turmoil, signals that the war on terror is over, or rather, that the U.S. is done fighting it with adequate deployments of ground troops.

The president has decided to shrink the Army and Marine Corps back to their pre-September 11th levels.

No longer will the U.S. military prepare to fight two major wars simultaneously.

It isn’t that security doesn’t require that level of preparedness; it’s that the president simply isn’t willing to do it anymore. Robust levels of conventional forces able to handle two conflicts aren’t all the president has deemed unnecessary for American security.

Despite no analysis that it would serve U.S. national security interests, Washington will also eliminate more of its nuclear weapons.

The New START Treaty, signed by President Obama and Russian President Dmitry Medvedev in December 2010, eliminates a significant number of nuclear weapons — U.S. nuclear weapons, that is. The treaty capped strategic launchers and warheads, but Russia was already below those figures. Translation: it only compelled the U.S. to reduce its arsenal.

The Russians have to build up to reach the cap.Yet while the U.S. -- the only member of the nuclear club without a program to modernize its nuclear weapons -- disarms, China and Russia will continue modernizing their weapons, and Iran will steadily march toward a nuclear capability.

The president’s plan also announces his intentions to rely on missile defense systems to protect the United States and its interests abroad. Yet it’s hard to take his claim seriously, since under President Obama’s watch, in misguided attempts to please Russia, missile defense funding has been skewed to support regional missile defense abroad at a rate five times that of missile defense assets that protect the U.S. homeland.

Moreover, the President issued a signing statement in conjunction with his signing of the 2012 defense bill on the last day of 2011, Saturday December 31, that indicates he may disregard Congressional direction to prevent the administration from sharing highly sensitive data about the U.S. Standard Missile with Moscow-- in return for nothing at all.

Meanwhile, Iran, with contributions from Russian, North Korean, and Chinese entities, continues developing longer range ballistic missiles that may eventually be able to carry nuclear warheads to the U.S. homeland.

Congress has compelled the administration to develop a hedging strategy in the event that Iran can threaten the U.S. before the president’s European Phased Adaptive Approach (EPAA) is complete and able to provide needed protection of the homeland, and the administration has yet to do so.

Gutting the military and reducing its capabilities leaves the U.S. weaker, and advertises to the world, both friends and foes alike, that the U.S. is taking a break from defending its interests.

Americans are understandably tired of war, and that’s why we have to remain prepared for a fight: to convince the world we’re ready and willing to keep the peace.

Rebeccah Heinrichs is an adjunct scholar at the Foundation for Defense of Democracies.