AP

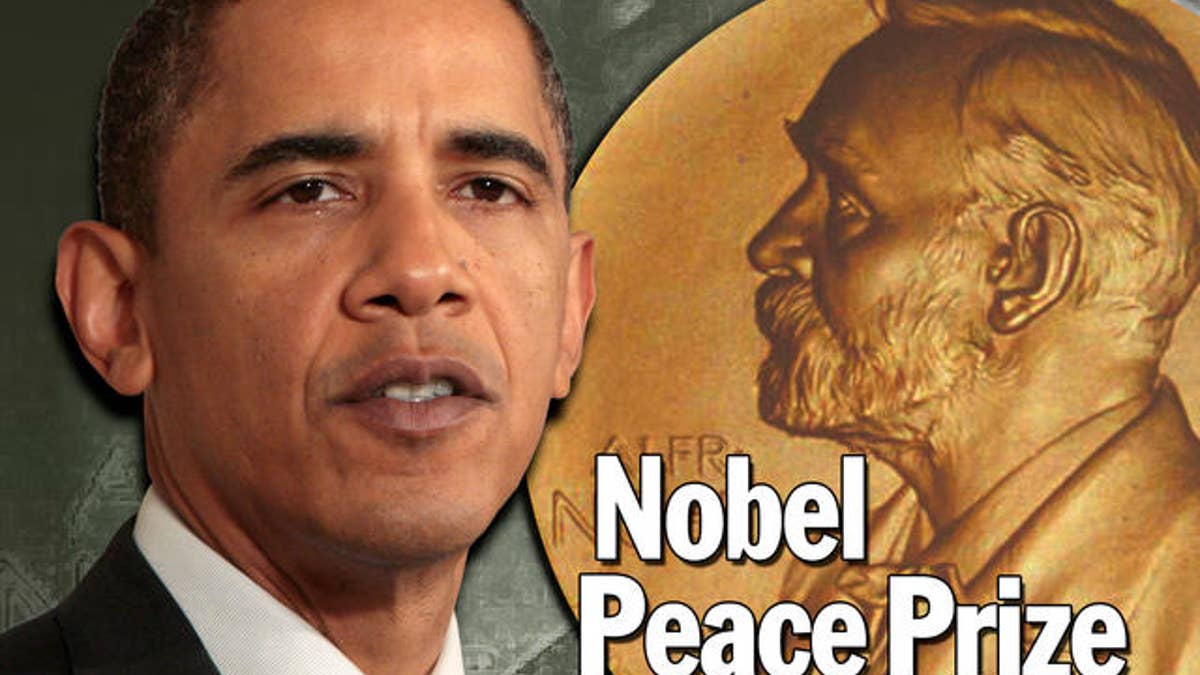

President Obama bowed to no man today. There were no more apologies for America. In accepting the Nobel Peace Prize, he spoke more about war than peace. And he stunned his audience by speaking, eloquently as usual, some plain “hard truth” about the world as it is, not as the men and women at Oslo pretend that it is, or as we might like it to be.

He made a case for war to keep the peace. Make no mistake, he said. “Evil does exist in the world.” It had to be fought. And he could not “stand idle in the face of threats to the American people.” Not for all the peace prizes and accolades in the world.

The non-violence of Martin Luther King and Gandhi “would not have halted Hitler’s army,” he reminded those assembled. And treaties and diplomacy would not persuade fanatics like Al Qaeda to lay down their arms. We all had an obligation to fight such evil. This is what America had done in Europe, he reminded those Europeans who often prefer to forget America’s sacrifice on their soil. This was what America was doing now in Afghanistan, and would it continue to do, unilaterally, if necessary, but he hoped, in concert with others who favored such “just” wars.

He embraced ideals, but spoke as a realist. Wars were ugly. Soldiers and civilians would die. But sometimes they were necessary. Like now. “The instruments of war,” he said, “do have a role to play in preserving the peace.”

The rebuke to those who criticized America and its motives was subtle, but unmistakable. In many countries, he added, there was “a deep ambivalence about military action today, no matter the cause,” and also a “reflexive suspicion of America, the world’s sole military superpower.” But America, he reminded his audience, had “helped underwrite global security for more than six decades with the blood of our citizens and the strength of our arms. The service and sacrifice of our men and women in uniform has promoted peace and prosperity from Germany to Korea, and enabled democracy to take hold in places like the Balkans,” he said. And America had done this not to “impose our will,” but to build a better world.

This is probably not what the Nobel Committee expected or wanted to hear. The speech was interrupted by almost no applause, except when he reiterated his pledge to close Guantanamo to avoid compromising the very American values we seek to defend.

His audience sat silent when he said that even humanitarian wars were sometimes justified, as in the Balkans – another instance in which American leadership helped end a killing field on European soil. “Inaction tears at our conscience,” Obama said, “and can lead to more costly intervention later.” That was why all “responsible nations” had to “embrace the role that militaries with a clear mandate can play to keep the peace.” That was why NATO remained indispensible.

The world could not stand idly by while governments brutalized their own people, he said in his 36 minute-long speech. “When there is genocide in Darfur; systematic rape in Congo; or repression in Burma – there must be consequences,” Obama said. He did not have to state the obvious: So far, there have only been resolutions and peace envoys –hot air.

The new threats we faced – such as weapons of mass destruction potentially in the hands of “a few small men with outsized rage”-- required new solutions. To avoid war, he said, at least three things were required.

First, the words of the international community had to mean something. “Those regimes that break the rules must be held accountable. Sanctions must exact a real price. Intransigence must be met with increased pressure – and such pressure exists only when the world stands together as one,” Obama said.

That message too, was unmistakable. Iran and to North Korea could not be permitted to “game the system.” Those who claimed to respect international law – were Russia and China listening? – could not “avert their eyes” when those laws were flouted. Those who care for their own security “cannot ignore the danger of an arms race in the Middle East or East Asia” and “cannot stand idly by as nations arm themselves for nuclear war.” Tough sanctions are clearly in Obama’s deck of planned policy cards.

Second, echoing President George Bush, his much unlamented predecessor, he said that America had to continue struggling for political and human rights. Rejecting the debate between America’s idealists and pragmatists as a false choice, President Obama said that peace would not prove stable in places “where citizens are denied the right to speak freely or worship as they please; choose their own leaders or assemble without fear.” The peoples of Burmas, Zimbabwes and Irans of the world should take note: Hope and history were on their side. America would strive to free them, through engagement, his obviously preferred tactic, but if necessary, isolation.

Third, he said, America would struggle for economic rights and prosperity. A “just peace” included not only civil and political rights, not just “freedom from fear,” but “freedom from want.”

He ended on an irony. As globalization was bringing us together, fear – of loss of race, tribe, race, and religion – was creating conflict. Religion, in particular, was being distorted to justify the murder of innocents. Al Qaeda and its ilk had “distorted and defiled” the “great religion of Islam” in the name of “holy war.” But there was nothing holy about the war they waged, he declared. In fact, no “Holy war” could ever be a “just war,” he argued, because “if you truly believe that you are carrying out divine will, then there is no need for restraint.” There was no need to “spare the pregnant mother, or the medic, or even a person of one’s own faith.”

Obama adamantly rejected this view. Such a “warped” view of religion, he said was anti-religious. “For the one rule that lies at the heart of every major religion is that we do unto others as we would have them do unto us.”

This was an unusual speech for Obama. Gone was his usual triangulation. This lecture had none of the internal contradictions that marked his West Point speech on his surge in Afghanistan. While there were occasional references to his earlier theme of the audacity of hope, this was the speech of a president, a realist now charged with the safety and fate of his people and much of the world. These were the words of a leader.

While espousing the requisite humility --how the prize was premature, why he was not yet worthy – President Obama stood tall today. Now let us see if he translates these fine words into policy. And if he does, will he be nominated for such a prize when he finishes the four, or eight years of his presidency?

Judith Miller is a writer, Manhattan Institute scholar and Fox News contributor.