Jared Cohen: The relationship between JFK's assassination, a country in mourning and The Beatles arrival in America.

Jared Cohen, the author of 'Accidental Presidents: Eight Men Who Changed America,' reveals how Paul McCartney and The Beatles reacted across the pond when news broke that President John F. Kennedy was assassinated in Dallas on Nov. 22, 1963.

On November 22, 1963, while President Kennedy prepared to face the political gauntlet of Dallas agitators, something extraordinary was happening across the pond and it was about to invade America.

It was a miserable and rainy day in England – more cyclonic in character than normal for that time of year – but that was not enough to keep Beatles fans from lining-up in record numbers to purchase the group’s second album, “With the Beatles.”

With more than half a million advanced copies sold, there was no doubt the album would be a smashing success in Europe. But for the first time, the Beatles would go on sale in North America and everyone wanted to know if Americans would buy into the hysteria.

At the time, Americans knew almost nothing about the Beatles. Their manager Brian Epstein had landed a short profile to air on the “CBS Morning News with Mike Wallace” the same day as the album’s release. For Americans, this was their first glimpse of the Beatles. The segment told the story of how “these four boys and their dishmop hairstyles [became] Britain’s latest musical and in fact sociological phenomenon.” It was slated to re-air that evening with Walker Cronkite, but unexpected events meant that never happened.

President Kennedy was shot dead at 12:30 P.M. as his open limousine made its way through Dealey Plaza in Dallas, Texas.

At the time of the shooting, the Beatles were in the middle of their fourth European tour and getting ready for a double-header concert at the Globe Cinema in Stockton.

Also performing that evening were the Kestrels, Peter Jay & the Jaywalkers, The Vernon Girls, The Brook Brothers, and the Rhythm & Blues Quartet. But, the Beatles were the main attraction. They were backstage in the dressing room and they had not been on yet.

There was no television or radio at the venue, but someone had come in to tell them. As Paul McCartney told me in his first interview exclusively on this topic, “We were all gobsmacked, as we would say. And, it was oh my God, wait a minute, is he dead? I seemed to remember following it closely trying to get more details like anyone, wait a minute, he’s been rushed to the hospital, well that’s a good sign. Maybe they can do something. But obviously as we all know, it turned out that there was no saving him. His injuries were too bad. So, it just became a very sad time for us because we had admired him.”

There is an extraordinary irony that while Beatles fans cried in hysterical fan worship of the fab four, teenagers across the Atlantic shed tears of melancholy over the loss of a man that they, too, had worshiped.

It is an experience that they wouldn’t understand or comprehend until December 8, 1980, when another madman named Mark David Chapman shot and killed John Lennon. But that evening, the concert went on as if nothing had happened.

Vernon Girl Jean Owen, now Samantha Jones, thought to herself, “God, the audience will be crap tonight, [but] you still have a job to do.”

Shockingly, the audience acted as if nothing had happened. Geoff Williams of the Kestrels, who opened for the Beatles that evening, recalled, "I honestly don't think the audience reaction to that second show was any different from any other night of the tour. It might sound strange, but this was an audience of young people who loved the Beatles, and they had come along for a good time. They were too young to have understood the implications of what happened."

By the time the Beatles went on stage, the news of Kennedy’s death had not yet reached them. “I would imagine that we didn’t know he was dead,” Paul remembered, “We had just known something terrible and dramatic had happened, because I don’t have any recollection of doing the show in a stunned state.

"Accidental Presidents" author Jared Cohen and Sir Paul McCartney (Courtesy of the author)

Although even just the fact that he had been attacked, was shocking.” But the Beatles were in a whirlwind and living very much in the moment. By the time they left the dressing room and climbed on stage, what had happened to President Kennedy was no longer top of mind.

It seems hard to imagine, in retrospect, but as Paul reminded me, they were in a kind of trance and there is this aspect of being a rock star where you just do your show. “You just did what you had to do,” he said, and “it wouldn’t be a case of us just stopping and telling the audience something terrible has happened so we’re going to cancel the show, it was just get on with it and do our thing. In those days, doing a Beatles show, real life didn’t enter into it. It was just screaming and songs and adulation and that blocked everything out. So, I don’t have any specific memory of being on stage and thinking we were in the middle of this terrible thing, even though I think we were aware that something like this had happened.”

By happenstance, the show was cut short anyway, although not for anything related to the horrific news. John Lennon was only partway through “Twist and Shout” when a crazed fan rushed the stage first to hug George Harrison and then make an attempt at John.

The security guards ultimately caught up with the teenage girl and forced her off stage, but not before the curtains abruptly closed and the Beatles were rushed out of the theater and back to their hotel.

So common were these types of events, however, that despite the added significance of the day, Paul still had no recollection of the concert incident other than to say, “We quite enjoyed [those kinds of incidents] because we didn’t fear them [our fans]. We didn’t think it was anything, just pure hysteria. It was just pure fan behavior, they wanted to say I was the one who got on stage and gave George a hug or I touched John or I grabbed Paul or whatever, and so that was quite a reasonably common occurrence and our security guys would just kind of run up to them and grab them and we just knew that this is kind of what would happen sometimes at our concerts.”

It was only after the show and later in the hotel that they started to see how the story unfolded. According to Paul, they were all glued to the television.

He remembered the “black and white images being shown on the way to the hospital, then a spokesman outside the hospital,” and of course, the news that the president was dead.

They had been stunned earlier when they first heard he had been shot, but news of the death “was a huge shock” and left them “white faced.”

More from Opinion

Even in the midst of a whirlwind where nothing seemed to matter other than the music and the fans, the finality of Kennedy’s death was rattling. “The color drained out of us all,” he remembered and “we just stood there in shock, like, ‘Oh my God, the president of America has been assassinated in our time?’ Because the [only story] we knew [like that] was Lincoln … Now suddenly here it was, a modern-day president, who we admired greatly, even though we didn’t know that much about his policies. The stories were filled in later of why there might have been people who wanted to assassinate him. At the time, we didn’t know any of that, so it was just a savage act that left us speechless.”

It felt strangely personal for the Beatles, even though they had never been to the U.S. and wouldn’t meet a U.S. president until Bill Clinton. But they were fans of John F. Kennedy.

“He just seemed like a breath of fresh air,” Paul remembered, “It was a kind of fan worship because we didn’t really know much about him. We just liked the idea that there was a good looking guy as president of the United States, that he was a Catholic, so this was rather interesting, it was a little bit out of the ordinary.

We liked his speeches. We heard his speeches. We thought he had a very good manner. And to us he represented America in a very good way and a very youthful way, which we could identify with.”

Prior to Kennedy, they hadn’t really been able to identify with American presidents. There had been people like Eisenhower, but he was a general and represented war times and therefore, wasn’t interesting to them.

“But suddenly there was this very charismatic and handsome guy,” Paul remembered, emphasizing, “I don’t think you can take that out of the equation because he was very much that. And with a first lady who was very elegant and youthful.”

As shocking as that moment was, it really came and went pretty fast. They were caught in the extraordinary momentum of what was being dubbed “Beatlemania” and nothing else seemed to matter.

Events may have eclipsed their debut on American television and the assassination may have bumped the Cronkite spot, but that was for publicists to worry about.

The Beatles didn’t care, or spend any time thinking about those things. They were just in a whirlwind and if there was something about them on television, Paul said, they “wouldn’t even notice.”

The fact that a major album was being released, they would sort of know, he suggested, but they didn’t pay attention to the specifics. With regards to the CBS spot, Paul laughed off any suggestion that they were even aware, “I don’t even think at the time we knew who Walter Cronkite was. We came to America with all of that, well, Walter Winchell, who is that? It’s Walter Cronkite. And we were like, ‘Walter who?’ We didn’t know these people. We were just four innocent Liverpool boys at that point.”

But, their detachment from what was happening in America was part of what made the Beatles’ story so uplifting. After more than two weeks of reporting on the assassination, the media and the public yearned for a break.

The story had far from run its course and there remained strong public interest and many unanswered questions, but it was also a melancholy time and there was a desire to report on something more uplifting. However, it was not Mike Wallace who resurrected the story. Recalling the “four lads” from Britain, Walter Cronkite had remembered watching the segment and decided to fulfill CBS’s promise to re-air the Beatles segment on prime time, which he did on December 10.

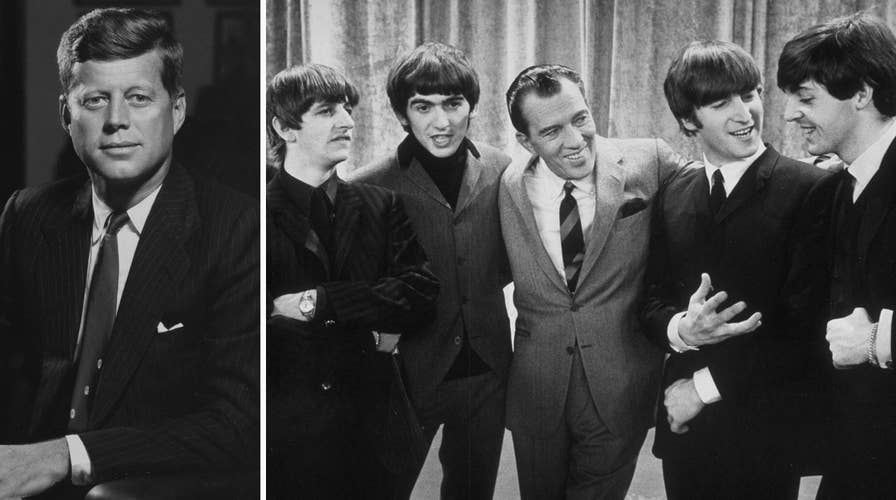

Cronkite’s publicity gift was fortuitous as Brian Epstein had been planning the first Beatles trip to America and was negotiating a coveted spot on “The Ed Sullivan Show.” An agreement was reached that the Beatles would appear twice, first on February 9, 1964, broadcast live from New York, and then on February 16 live from the Deauville Hotel in Miami Beach.

At the time, there was some awareness of the hysteria around the Beatles, but Americans would remain largely unaware of what was about to hit them.

While the Beatles rarely distinguished one trip from another, they recognized that the trip to America was different.

They gave no thought to the context of a nation in mourning, they were just excited. “We were kids who had just grown up admiring America for its music, its movies, for its movie stars, for the whole American dream,” Paul said. “Hollowed masses. That to me was America. Because we had grown up post-war, so it was freedom and all this glamorous music and stuff that we loved.”

The trip to America also represented a new challenge for them since they didn’t know if their music would translate to an American audience. “We didn’t know Americans,” Paul acknowledged. “We were just English guys and we might have met a couple Americans, or our relatives might have gone to America, but it was a far-off land that sent us music. So, we didn’t know any of the politics or how Americans were feeling. We knew that their world was devastated.”

The significance of the moment didn’t register for them. From their perspective, “We were just the Beatles going on tour.

So, world events like [America in mourning] didn’t really enter into our thinking because we were very specifically here and now thinking about the music, thinking about stuff we had to do, thinking about packing, it was all just very immediate and it was only … in later years when the history of it all unfolded that we realized … we were a healing factor.”

The timing was also right – they came to America months, not weeks after the assassination –and in retrospect that was clear to them: “America felt it was a long enough period … to come out of mourning and now find something to smile about and that was us and it was now you could forget yourself. You could forget your troubles you could forego the woes of the nation … [There] is this group and let’s party.”

On February 7, 1964, just seventy-seven days after Kennedy’s assassination, the Beatles arrived at John F. Kennedy International Airport, which had only been given its new name on December 18 the previous year (original name was Idlewild Airport or New York International Airport).

If there had been any question that the group would find success in America, that skepticism evaporated the moment they landed.

The hysteria started immediately and it never ended.

“We were on this staircase to the stars so that when we came to America what Americans saw was a fully formed beast,” Paul explained, as if to suggest that it shouldn’t have been a surprise. That same whirlwind that defined their European tours was now part of their American experience. They were caught up in the moment and the fans and paid no attention to the symbolism of the airport’s name or the size of Ed Sullivan’s audience. Their psychology was “Who is this Ed Sullivan guy? We are going to be on his show, is it a big show? We don’t know.” It was only later “that we discovered how big it was, how significant, and what it meant to America.”

The Ed Sullivan appearance was the inauguration of Beatlemania in America. More than 73 million people – 60 percent of American televisions – tuned in to hear them play songs like “All my Loving” and “I want to “Hold your Hand.”

If every teenager could tell you where they were and what they were doing when Neil Armstrong walked on the moon and when Kennedy was shot; they could do the same with “The Ed Sullivan Show.” It was magical and culturally transformative.

“We didn’t realize it at the time,” Paul reflected, but “Americans had never seen this before; four people in a band, looking like this, playing their own instruments, singing their own original music, four – dare I say it, handsome young boys.”

They were in the moment, marveling over the fact that “here we were in America and wow, we hear ourselves on the radio, WINS [with] Cousin Brucie – [as in Bruce Murrow] – [saying] ‘Ladies and gentlemen, the Beatles’ … [It’s like] ‘Oh my God, we are on the radio, oh my God. Wow!’ We were just so excited, so … we were[n’t] thinking of the Kennedy assassination.”

There is a case to be made that the Beatles filled a Camelot void left by JFK. After all, the demand for someone young and vibrant remained and the new president, Lyndon Johnson, didn’t fit the bill.

When asked about this, Paul paused as if he had never been asked this question before and said, “I wonder If we were seen as four Kennedy’s. I don’t know. It’s a long shot, but it could be possible. Certainly, there at the pinnacle of American attention, there had been this young, handsome, charismatic president who was no longer and … there was now this not so charismatic Texas guy who lifted dogs up by the ears” and took meetings from the bathroom.

During the LBJ years, civil rights and Vietnam were the two issues that captured the attention of America’s youth and the Beatles tapped into both of these issues in a profound way.

They spoke their mind and had an authenticity that was as appealing as the Kennedy charm, but less polished. But they had a massive platform and they intended to use it.

“Our opinions were unfettered by any sort of maturity, really,” Paul recalled. “We were just kids speaking our mind and I think from what I hear, that was really appealing to people. It was like, ‘oh my God, these guys are just talking. They are just saying what they think.’ And I think that was a big attraction to a lot of people.”

As they made repeated trips to the U.S. throughout the 1960s, the civil rights issue became personal to them. In September 1964, they learned their Jacksonville gig was to be a segregated audience. They were shocked. The only segregation they knew was Apartheid in South Africa and they wanted nothing to do with that.

They talked it over and informed the powers that be that they weren’t going to play. When asked why, they said “because it’s just a stupid and evil idea.” Faced with cancellation, the hosts ended up changing the rules and the concert went on.

Going forward, they also added a clause to their contract that they would “never play for segregated audiences.”

Vietnam was less personal, but they still felt an obligation to speak out. Paul had learned about Vietnam from Bertrand Russell, a philosopher who a friend had recommended he meet, which he did at his loft in Chelsea.

“Do you know about Vietnam, are you up to date?” he asked Paul, who subsequently sat for a lengthy briefing that he later relayed to John and the boys. Their publicist had told them not to talk about Vietnam, to which they said OK, knowing they would anyway.

They were “conscious young men” and when asked about it, they said what they felt, “greatly, even though we didn’t know that much about his policies. The stories were filled in later of why there might have been people who wanted to assassinate him. At the time, we didn’t know any of that, so it was just a savage act that left us speechless.”

Their publicist had told them not to talk about Vietnam, to which they said ok, knowing they would anyway. They were “conscious young men” and when asked about it, they said what they felt, “it’s not a good war. It’s not a good thing. Americans shouldn’t be in this.” Of course, their publicist is having a heart attack, what?? You shouldn’t be saying this.”

But they did it anyway on both Vietnam and civil rights and that was their power. They were inadvertent activists by virtue of their consciences desire to speak their minds. But they were also aware of their reach and that the same young people who had believed so strongly in Kennedy, were eager to know what they had to say.

As Paul said, “Outside the music was this thing that you kind of felt like [the Beatles] were speaking for you. [We] sort of said things like, yeah, Vietnam isn’t too cool.” And people would say, “Wow, I’m glad they said that because I’m about to be called up. So, it was a we were on your side kind of thing.”

CLICK HERE TO GET THE OPINION NEWSLETTER

The publicists, one of which he described as “a cigar-chomping, tubby guy” couldn’t do much about their outspoken nature and as Paul explained, “they were secondary and I’m afraid by then we were the bosses.”

In Paul’s words: “We were just recently doing that teenager thing, so we were just honest. It was just our nature. And I think to this day … it is very much part of what we are, what I am. What John was, certainly. What George was. What Ringo is. It is one of the great strengths of the Beatles, that we were put together as this gang of four who just happened to be in tune and happened to be honest and happened to be able to make some cool music.”

In the February 11, 1964, edition of the New York Daily News, Anthony Burton observed, “It’s a relief from Cyprus and Malaysia and Vietnam and racial demonstrations and Khrushchev. Beset by troubles all around the globe, America has turned to the four young men with the ridiculous haircuts for a bit of light entertainment.”

It may have been that it was just “light entertainment,” but perhaps it was more.

CLICK HERE TO GET THE FOX NEWS APP

In truth, the Beatles would have been successful regardless of the timing of Kennedy’s assassination and the country would have moved on even if the Beatles hadn’t come to America. But that doesn’t mean we should ignore the timing, the massive media coverage, the reality that this was an uplifting moment at a helpful time in America.

“I can’t imagine anybody really saying there isn’t any correlation because I think there was,” said Paul. “I think looking back on it America did need something,” especially the “younger generation.”