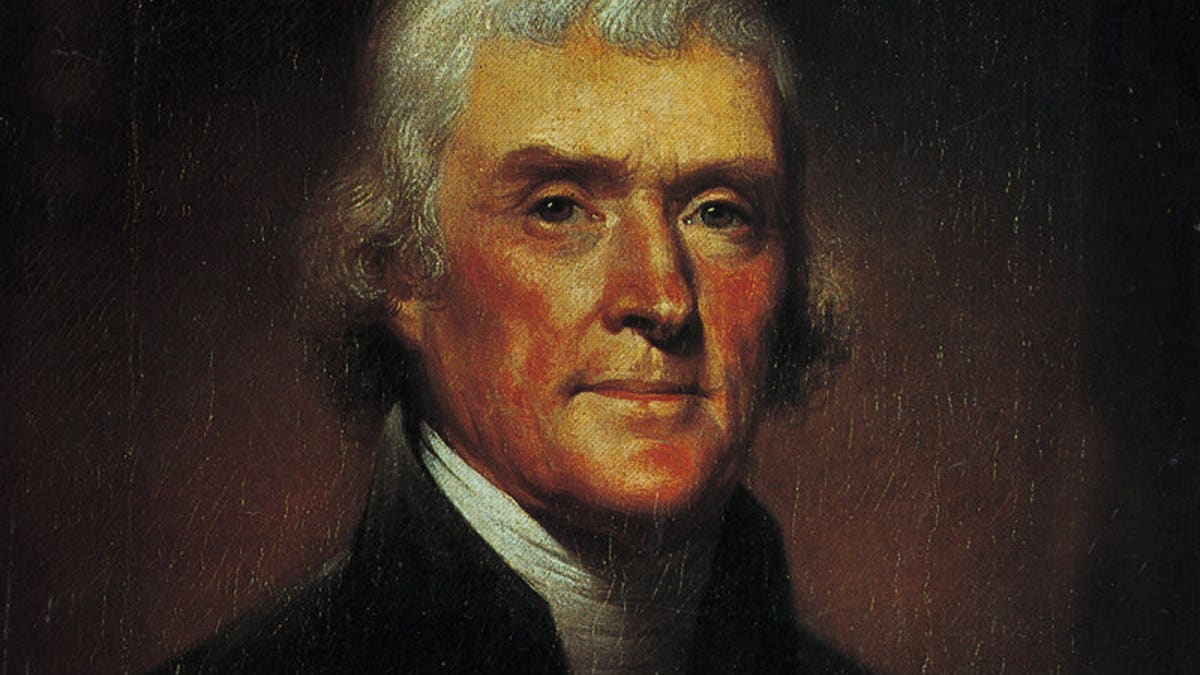

Deceptively simple words, those that we see above from the Declaration of Independence. The greatest words Jefferson ever wrote. Perhaps the greatest words anyone has ever written. Words that inspired men to pledge their lives and fortune to the cause, that inspired women to make countless sacrifices and that inspired nations to embark upon an experiment of freedom.

With Jefferson’s legacy increasingly in the public consciousness, it bears reflection that his words gave voice to a movement. Jefferson’s was a voice that changed the world. His voice was the voice of our nation. And in many ways, it still is.

In our new novel, “America’s First Daughter,” (William Morrow Paperbacks, March 1, 2016) an epic family saga about the Jeffersons, his daughter Patsy wonders if she should dare censor that voice by editing his papers for posterity. She and her family did edit those papers, but the more than 18,000 letters–now digitized and available to all Americans through the National Archives at founders.archives.gov–remain a remarkable commentary that still speaks with a familiar language of optimism about the nation.

Despite all his faults, contradictions and moral failings, Jefferson speaks to our desire to be and do better. Perhaps that is why he is so often quoted–and claimed–by both political parties.

To read Jefferson’s letters is to conclude that if there is an exceptionalism about this country, it’s that we’re an aspirational nation founded not on shared identity, but on shared ideals and a desire to better the condition of mankind. To that end, America has stumbled from the beginning and continues to stumble. But that wouldn’t have surprised Jefferson, who always believed there was room for improvement–whether it was the structure of the government of the nation he helped to bring about, the improvement of the general mind through public education or even his house at Monticello, which was perpetually under construction.

And almost all of what America gets right is still quintessentially Jeffersonian in nature.

To the extent that the United States represents a model of enlightened ideals and an inspiration for others to determine the course of their own lives, they are ideals most famously and poignantly expressed by Jefferson, the voice of the American Revolution.

To the extent that we believe in the civic duty of citizens to be informed and to vote, to protect the rights of free speech and a free press and to preserve the separation of church and state, we are furthering the core ideals of Jeffersonian republicanism.

To the extent that we offer asylum to the oppressed and champion regular Americans, we are following Jefferson’s vision for America. To the extent that we fund schools and libraries, we are chasing Jefferson’s dream of equal opportunity for all citizens through public education. To the extent that we explore new frontiers in space and science, we are walking in the footsteps of our insatiably curious third president.

As we find ourselves immersed in the midst of a nasty presidential campaign, divided as our politics have become, it might be tempting to conclude that our Founding Fathers, enshrined as they are now in marble, no longer speak to us or for us. Jefferson did not achieve everything we might wish that he had in the cause of liberty and equality, but what he did achieve revolutionized the world and began a conversation about what America is, what it should be and what it could be in which we all continue to participate to this day.

The election of 1800, which catapulted Jefferson to the presidency, was one of the most bitterly contested elections in the nation’s history and the first in which power peacefully changed between parties.

The vitriol of modern politics and presidential campaigns wouldn’t have been entirely unfamiliar to those present at and responsible for the creation of party politics during and after this election. And yet President Jefferson, in retirement, found a way to embrace his old friend–and political opponent–President John Adams.

Jefferson prioritized their shared beliefs in democracy and life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness–in short, in America’s promise–over their differences, reigniting a life-long friendship that ended only when they died within hours of one another on July 4, 1826, the 50th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence.

A lesson in that for us all.