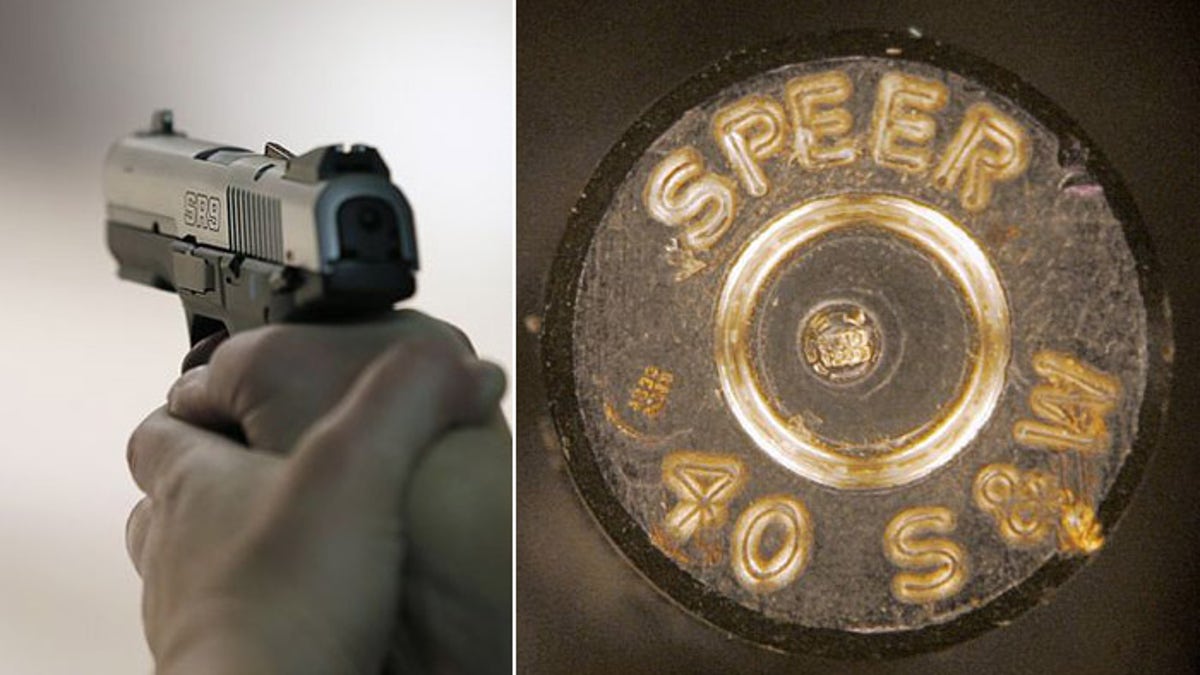

Microstamping technology is designed to leave a telltale indentation in the very center of the shell casing when the gun is fired. (AP)

An ambitious plan by Maryland to catalog the “fingerprint” of every gun sold in the state -- making dealers fire a shot and send in the spent casing -- is being scrapped, literally.

State authorities have conceded that the bullet ID program, enacted in 2000, cost $5 million, was plagued by technical problems and did not solve a single crime. Now, the 300,000 shell casings, one from every handgun sold in the state since the law took effect, will now be sold for scrap metal.

"Obviously, I'm disappointed," former Maryland Gov. Parris Glendening, whose administration pushed for the database, told the Baltimore Sun. "It's a little unfortunate, in that logic and common sense suggest that it would be a good crime-fighting tool."

But Second Amendment advocates say the program was doomed to fail.

“It was clear 10 years ago that this program was not going to work,” John Lott, president of the Crime Prevention Research Center told FoxNews.com. "Millions were spent on funding this program, money that could have been better used for actual police and law-enforcement resources.”

“It was clear ten years ago that this program was not going to work.”

Lott even predicted that the program would fail over a decade ago in an op-ed piece in the National Review in February 2005. Even though the state spent approximately $60 per gun to catalog each firearm's unique ballistic signature, critics, including Lott, said legally purchased guns were typically not the ones wielded by criminals. They also said the program suffered from widespread erroneous entry of data and the inadequate software often resulted in hundreds of "matches" being found for each casing tested.

According to the Baltimore Sun, the hundreds of thousands of “fingerprinted” casings were stored in envelopes kept in boxes inside an old fallout shelter beneath the Maryland State Police headquarters in the Baltimore suburb of Pikesville, filling three massive rooms, each secured by a combination lock. Each shell was stamped with a barcode and then photographed by forensic scientists to create a database they hoped would yield matches to casings collected at crime scenes.

FILE: Undated: A model 1911 pistol is held in the hands of an assembler at the Smith & Wesson factory in Springfield, Mass.

“The Maryland ballistics database has been a failure from its inception,” Amy Hunter, spokeswoman for the NRA's Institute for Legislative Action, told FoxNews.com. “The program has been effectively defunct for several years. Funding has been discontinued, and the personnel associated with the program have been reassigned, yet the requirement persisted and its costs were passed on to the consumer. The NRA-ILA supported the repeal and is pleased it’s now in effect.”

In theory, the “fingerprinting” system is sound science. Scratches are etched onto a casing which enables them to be matched to the weapon that fired the shot. The program was expanded from a limited, but successful National Ballistics database which only collected casings from crime scenes.

Throughout its run, the Maryland database helped investigators a total of 26 times, but with each case, they already knew which gun was in question, state police officials said. New York had followed Maryland’s lead and created a database of their own, but funding was pulled in 2012 when that program proved ineffective. Some backers say the program could have worked if authorities had stuck with it, claiming that handguns used in crimes are typically as old as 20 years or more.

In 2008, the Justice Department asked the National Research Council to study the value of creating their own database similar to the one in Maryland and New York, but it was determined that it would not be a good use of funds.